Peru. The Asheninka Cultural Identity and Spirituality.

The Asheninka live in the departments of Pasco and Ucayali, which are part of the central jungle of Peru. They are estimated to be around 15 thousand people. The term Asheninka has to do with blood family and community family and means ‘Our kinfolks’.

The social environment of the Asheninka is based on family, which is considered the nucleus of the community. Marriage between a man and a woman implies reciprocity and mutuality. Each of them has their role; the women of the community raise children, and therefore they play a special role in the family, while the men are those that create and strengthen social relationships in the community. Singlehood status is seen as a sad experience, single men or widowers are considered to be unhappy, because they have to live with their relatives, they have their meals separately, in another house, and they are not supposed to offer their friends even a ‘masato’. For this reason, a bachelor loses prestige and has no influence within the Asheninka community.

The Asheninka make a clear distinction between family house and social house. The first is associated with women, while the second with men. The social house is the place where the sherampares (men) meet to share their experiences, to talk about hunting and other topics. For their part, the tsinanis (women) gather in the family house, where they take care of their children and cook.

The Ashaninka community is guided by a chief, the jiwari or jewawentseroni; he is generally an elder. Decisions are taken

during community assemblies.

What sustains the coexistence of the Ashaninka community are its ancestral traditions, such as the Mink’a and the faena (communal work for purposes of social utility), its principles and values, such as harmony, parity, freedom along with dialogue, sharing, respect and honesty.

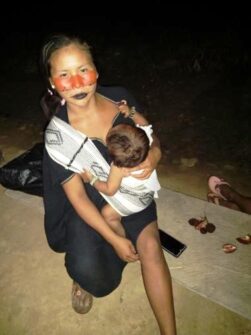

The Asháninka language is spoken in the central eastern territory of Peru, in the departments of Cusco, Junín, Pasco, Huánuco and Ucayali. Such a wide distribution certainly offers multiple dialectal varieties. However, speakers of these different tongues can often understand each other. The Asháninka traditional dress for both, men and women, commonly known as kushma, is a robe made from cotton that is collected, spun, dyed and woven by women on looms. Dyed stripes always figure in the design, vertical for men’s garments and horizontal for women’s. The women’s kushma is adorned with snail shells and small bones. Ashaninka mothers use the aparina to carry their baby. The chief of a community wears a badge, representing a crown with snake figures woven with black thread or another colour and adorned with large macaw feathers which are embedded in the crown. He also wears a tuft of small feathers hanging on his shoulders.

The feathers, which have particular meanings to this ethnic group can be of curassows, herons or some other bird. The Ashaninka also make up their faces by drawing figures with achiote paste. Each figure has its meaning. Others have blue-coloured tattoos on their cheekbones. All these social traditions, typical clothes and make up, create the cultural identity of the Ashaninka.

The Ashaninka celebrate life with festivals such as the masato festival, which takes place at the time of full moon, in the summer months. It is a moment to share typical food and drinks. Masato and their typical food are also elements that are part of the Ashaninka cultural identity. This ethnic group also like to celebrate the end of a mink’a, which can be the construction of a house or another activity.

On these occasions all participants in the mink’a drink masato, eat traditional dishes, share stories and experiences, sing their traditional songs and dance to the rhythm of the drums, keeping alive, by doing so, their ancestral customs.

The Asheninka worldview is tripartite. This ethnic group believe that there are three existential spaces: Jenoki-sky (God, sun, moon and stars), Kepatsi-earth (man, nature, animals, rivers and other living beings) and Jaavike-underworld. The universe to the Asheninkas is characterised by the harmony between men and the spiritual beings, and between men and nature.

The Asheninka spirituality is rooted in the ancestral wisdom they have received from their ancestors. Creation, to this group, is the expression of the divine that reveals itself in many different ways: for instance, through animals that are considered sacred or somehow associated with the divine such as the jaguar, the manitzi, and the puma chánari. There are also other sacred animals, which indigenous people are not supposed to kill or eat, such as the caracara or atatawo bird, since they are believed to be shamans that transformed themselves into animal forms, therefore eating them would be an act of cannibalism. The anaconda is called yacumama (water mother) by indigenous people in South America. Besides sacred animals there are also places and plants that are sacred to the indigenous peoples: the salt hill, some sites in the Qollpa village, waterfalls, leafy trees (shihuahuaku, lopuna and others), medicinal plants (piri piri, matico, coca and others).

Masato is considered both a sacred and nutritional drink, and is used in social and ceremonial gatherings.

Drinking masato during festivals or family celebrations strengthens family and community relationships. Finally, the Ashaninka’s ancestral wisdom is present in their mythological stories, as oral narrations, which have been passed down through generations.

Jhonny Mancilla Pérez