‘Abadinto’. Naming a child among Asantes.

In the Akan societies in Ghana especially among the Asantes, names and the process of naming are essential since everyone and almost every living entity has a place and mission in the world.

The name of a person or entity reflects their purpose in life. The adinto or abadinto (‘to throw a name’) or naming ceremony usually takes place at the father’s house on the eighth day, that is, a week after and on the day the child was born. Newly born babies are not allowed to be brought outside of their homes until this ceremony is performed.

The purpose of waiting seven days after the birth of a child is to ensure that he or she has come to stay on earth (Asase Yaa) and will not prematurely return to Asamando (‘abode of the ancestors’).

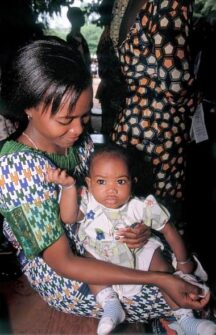

In addition to the day name, Asantes frequently give children the name of an elder relative, either living or deceased. Photo: 123rf.com

Cultural beliefs dictated that after eight days, the infant was likely to survive and could be provided a name. In addition to the day name, Asantes frequently give children the name of an elder relative, either living or deceased. Naming the child is the responsibility of the father’s (agya) family. It is also believed in many communities that evil spirits and other negative influences may bring bad luck to the child. It is the father of the child that has the responsibility of naming the child on the day of the ceremony. Until that day, the child is regarded as a ‘stranger’ (ɔhɔho). Thus, the Asante say to the new infant child, woaba a tena aseɛ (‘now that you have come, sit down or do stay’); this phrase is a greeting that is said to an infant to wish the child long life.

The Ceremony

Before the scheduled day of the ceremony, items such as gin (nsa), two glass cups (nkuruwa), a bottle of water (nsuo), a mat (kɛtɛ), a calabash (pakyi or kora), and a broom (ɔprae) for young women and a cutlass (nkrante) for boys are gathered. Early in the morning of the scheduled day, two elders (mpanyimfoɔ) of good character from the father’s family are sent to go and bring the child and mother from the mother’s house. One elder is chosen to perform the ceremony; if it is a male child, that person chosen will be a man and conversely for a female.

Naming the child is the responsibility of the father’s family. Photo: Swm

The mother bathes the infant and they both dress in white cloth and stay indoors until the ceremony begins. Certain sacred beads (such as bɔdɔm, ahenewa, and abobɔe) are put on the child, and marks made with white clay (hyire) and, specific to this ceremony, are put on both the child and mother. In the early morning, close relatives and friends of the mother help in the preparation.

The ceremony starts with an opening libation (mpaeɛ) poured by an elder who announces the occasion and the purpose of it. The mother’s family provides the drink used for this libation, which is poured at every doorstep and the main entrance to the house. The father’s family provides the drink for the second libation. After this libation, the child is brought out and stripped naked. The child is then placed on a prepared area of the ground or on a comfortable cushion.Mostly, strong drink and water are placed on the tongue of the baby by an elder dipping a finger into the liquid. Strong drink and water are used to tell what is good from what is bad.

Among the Asantes too, babies are raised toward the sky three times as an introduction to Heaven and Earth. Libations are again poured as protection over the child.

Village. The naming ceremony is a celebration of the community. Photo: Swm

The father’s female or male elder then dips her or his forefinger into the gin or uses a leaf and then drops it on the child’s tongue and says, “when we say that it is gin (symbolic of untruth), say that it is gin” (sɛ yɛka se nsa a ka se nsa) three times. The elder does the same with the water: “when we say that it is water (symbolic of truth), say that it is water” (sɛ yɛka se nsuo a ka se nsuo). Both of these tastings advise the child to seek and tell the truth and to distinguish it from falsehood as she or he tries to live a righteous and ethical life.

The child’s name is given by the father (agya) and the child is then given a name: “We will call you…and this name means….” (yɛbɛfrɛ wo… ne asekyerɛ din yɛ…). “From today onward, we will call you… (ɛfiri nne rekɔ yɛbɛfrɛ wo…).

The second name of the child can come from consulting an ɔkɔmfoɔ (spiritualist/healer) or ɔbosomfoɔ, an elder or ancestor of the father’s family of good character, circumstances of the child’s birth, and the like.

As such, the second name is properly called agyadin (name from the father), which was synonymous with a family name or surname.

Most Asantes have two names, their ‘soul’ name, and the name from their father at birth before the arrival of the Christian orthodoxy in present‐day Ghana. Today, many Asante people have a first, middle, and last name or surname.

A day name

The baby is given a name concluded with a family name (surname). The name is then called out for the guests to repeat loudly to formally welcome the child into the world. The child is given a day name based upon the gender and day of the week on which the child was born.

A child born on Sunday will have his or her naming ceremony on the following Sunday and will be given the first name, Kwasi or Akosua. For the Asante and Akans in general, a child’s first name or kradin (‘soul name’) is routinely given based on the Akan week (nnawɔtwe, ‘eight days’). A child born on Monday is named Kwadwo (male) and Adwoa (female); Tuesday, Kwabena (male) and Abena (female); Wednesday, Kwaku (male) and Akua (female); Thursday, Yaw (male) and Yaa (female); Friday, Kofi (male) and Afia (female); Saturday, Kwame (male)

and Ama (female).

The child is given a day name based on the gender and day of the week on which the child was born. Photo: Swm

There are other praise names given to an Asante child: Bodua (protector, leader), Okoto (calm, humble), Ogyam (good, humane), Ntonni (advocate, hero), Pereko (fearless, firm), Okyin (adventurer, itinerant), and Atoapem (ancient, heroic)

As part of the outdooring, male infants are circumcised, and female infants have their ears pierced. However, currently in Ghana, some of these practices including circumcision, and ear piercing are done after birth within the hospital, and the Outdooring serves as a symbolic ceremony and celebration of birth.

The child is then presented to the community; this is called ‘outdooring’ because it is the first time the child is taken out of the house. A final libation is poured to consecrate the ceremony, and blessings for the child and his or her family are requested along with requests for the child to be an obedient, truthful, and righteous member of the community.

Next, the child is addressed by their name and told what family and community members expect of him or her. Songs of praise can be sung to the child. Those in the audience bring the child gifts (such as money [sika] or clothing [ntadeɛ]) and feasting with singing and dancing begins. The ceremony officially ends. (D.D. D. A.)