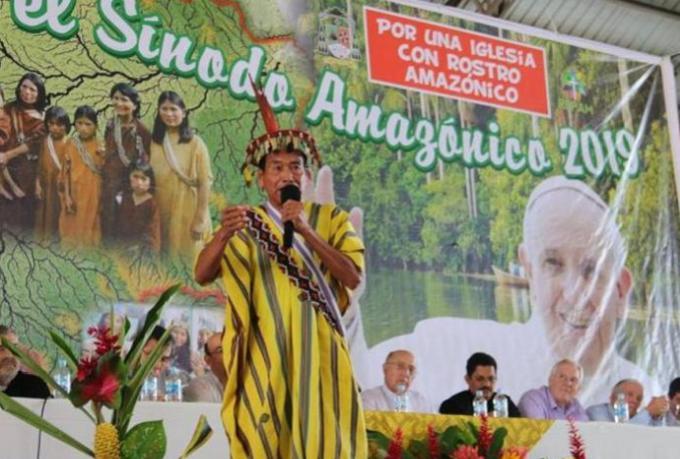

Towards the Synod. ‘Amazonising the Church’.

The defense of the environment and its peoples. New ministries for the Christian communities. The role of women. Ahead of the Pan-Amazon Synod to be held in Rome in October, we speak with Mons. Evaristo Pascoal Spengler, Bishop of Marajó.

“Some of the aspects that cannot be omitted during this synod: the prophetic and daring position of the Church on integral ecology, the model of occupation and the future of Amazonia, dialogue with the world of science, an agenda of coherent proposals to be presented to governments and the whole of society. A further important question regards the indigenous peoples and other traditional populations of Amazonia. The Church is already in solidarity and allied with their struggle but many do not yet have citizenship either in the Church or in society”, Mons. Evaristo Pascoal tells us.

The sixty-year-old Brazilian bishop also sees as the internal themes of the Church: “A Church that is missionary, Samaritan, present, in solidarity and that walks with its people.

Today, the Church has the habit of visiting the most distant internal communities once a year. It looks like a ‘tourist Church’ rather than a Church walking with its people.

If the Eucharist is the summit of the Christian life, it is scandalous that the Church does not guarantee thousands of the faithful access to this sacrament”.

Mons. Evaristo Pascoal refers to the working document (Instrumentum Laboris) saying : “ The document opens the debate on a model of non-celibate ordained ministry. Again, the majority of the leaders of the communities in Amazonia are women, but almost always deprived of decision-making and ministries. The Instrumentum laboris calls for reflection on an official ministry for women. Will there be the possibility of a diaconal ministry for women? A Church with an Amazonian face, with indigenous and inculturated ministers, is a challenge that requires bravery in seeking new paths. Then, the training for ordained ministries and that of the laity must be more inculturated, more missionary and closer to the reality of the concrete life of the people”.

The bishop continues: “It is necessary to pass from a Church of indigenism to an indigenous Church that expresses faith in Jesus Christ through the cultural and religious categories of the indigenous peoples. What teachings can the universal Church receive from the spirituality and experience of the indigenous peoples? The Church in Brazil has had an Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI) for 45 years.

It has well served the indigenous cause and expresses a way of being of the Church, not preoccupied with itself, the liturgy, catechesis or other questions, but preoccupied with the great causes of indigenous peoples such as land, culture, health, education and rights. This is the sort of Church we may call indigenous.

If the Church has anything to offer the indigenous peoples, it must also receive something. Living together is always a dialogue. The indigenous peoples are many and it is not easy to generalise. For the sake of simplicity we may say that the indigenous people do not have ‘sanctuaries’ or a sacred space because all is sacred, everything is one great sanctuary. God is present in everything in such a way that there is no such thing as impious life and religious life. Their land is sacred, their history is sacred, their myths are sacred, life is sacred and also time. We can learn from the communities of the indigenous populations, from their sharing, their simplicity of life, their exercise of power, from their communal decision-making and their awareness of belonging to a people. But it is not only the Church that must learn; all society must learn from the indigenous populations, especially as regards the care of our common home”.

It is precisely with the point of view of the environment in mind that Mons. Evaristo says: “In Laudato Si’ the Pope affirms that all is connected: economy, free time, work, social life, spirituality. But all is connected also because the world is one great unit of life: land, air, forests, the sun, the rocks, the immense biodiversity, climate, the stars, the seas, human beings and God. Ecology, on the other hand, is connected to economy, politics, agriculture, engineering, urban life, health, food and spirituality. Everything is connected. Integral ecology is the whole of ecology, undivided, which concerns the whole person and their relations with everything.

In Amazonia too, all is connected: the forest, the rivers, the soil, the rains, animals, insects and human populations. Today, two models that are different from and even opposed to each other, are being followed in relating to Amazonia, the result of two visions of the world. One is the predatory model. It includes deforestation, the extraction of minerals and oil, and the production of energy. It increases cattle-raising and monoculture which lead to deforestation (already 20% of the forest has been lost). It generates concentrated income, slave labour, sexual exploitation, people trafficking, the poisoning of the soil and the water, the reduction of rainfall (in deforested areas the dry season is getting longer by six days every ten years), the expulsion of people from the forest, the elimination of respect for the law, the deaths of leaders, environmentalists and pastoral agents. Some of the victims of this model: Chico Mendes, Sister Dorothy Stang, Father Josimo, Father Ezechiele Ramin and many others.

The other model is social-environmental–ecological. It values the conservation of the forest and biodiversity, the socialisation of the land and its resources, the redistribution of wealth, the conservation of the traditional populations and the placing of ‘the human being’ in the forest. It develops with a promising market of fruits, coconuts, cra’t products and pulp, medicinal plants, oils, nuts and ecotourism. This model has great potential; it coexists with the forest and interacts with it without destroying it”.

Since 2016, Mons. Evaristo Pascoal has been Bishop of the Prelature of Marajó, an archipelago of more than 2500 islands situated at the mouth of the Amazon River in the region of Pará. His experience in these few years at the service of the local Church has led him to reflect deeply on the meaning of a synodal Church. He says: “The synodal Church is one that seeks new answers to new problems because the old answers were useful for the old problems but they may not help to solve new ones. The synodal Church is an adult Church, mature and co-responsible for the decisions it takes, in which the Pope, being faithful to apostolic tradition, listens to the Church before taking decisions. The synodal Church is a collegial Church that takes decisions in common and respects the autonomy of every situation and organisation. The synodal Church is a Church in which those who exercise a ministry must encourage others, confirm them in the faith, and be the first to serve and to value everyone. The synodal Church is a Church in which all the baptised are responsible for the Church, not only those who are ordained, and in which our baptism makes us equal while services and ministries render us different but not superior.

The synod for Amazonia made us create new verbs or use verbs we did not know such as ‘synodising’ and ‘Amazonising’. ‘Synodising’ means being a Church with a permanent synodal spirit of dialogue, of listening, of constant searching for new paths of evangelisation; a Church that is faithful to the Kingdom and to the prophetic and missionary spirit of Jesus. ‘Amazonising’ means being guided by the spirit of Amazonia and its peoples. Some time ago there was talk of internationalising Amazonia, saying that it is far too important for the world for it to be governed by just a few countries.

Today we are discovering that we must not internationalise Amazonia but Amazonise the Church and the whole world”. (Dario Bossi)