Nomads and Farmers, Old and New Fights in Africa.

In the last years one of the different ethnicities that live on the continent was put under the spotlight in West and Central Africa due to the violence and turmoil that other groups attribute to it.

This ethnicity has several names (Peul, Fulani and Feulbe),

and several ‘surnames’ (Toucouleur, Mbororo, etc.), and

some related critical issues.

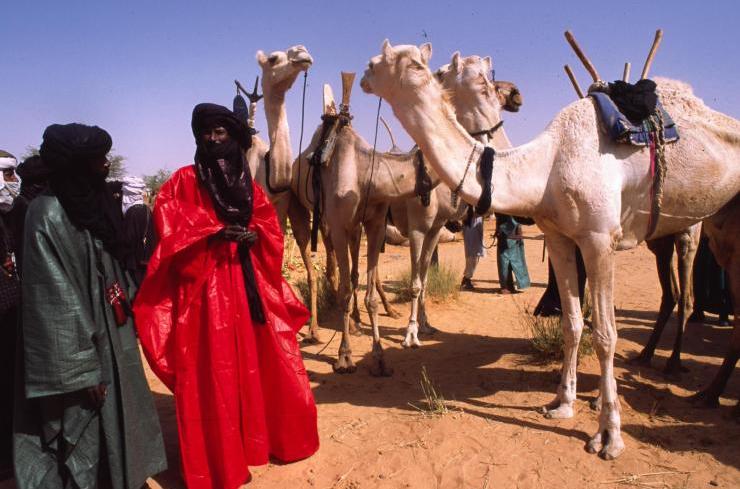

According to estimates, nowadays there are about forty million Peuls living in fifteen African countries. There are some common cultural and religious elements among the different clans and tribes spread in this huge area – elements that create the Peul identity or code of conduct (pulaaku, or feulbete).

The first of these common elements is the language, known as pulaar in West Africa and as fulfuldé or fula in other contexts. But on the ground the reality is different, and a Toucouleur living in Senegal is quite different from a Mbororo living in Central African Republic or Cameroon, even if they can both be considered as Peuls. And there are differences even within the groups.

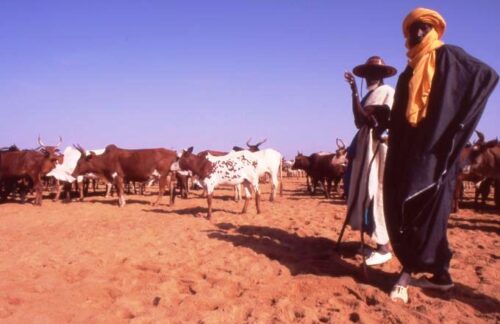

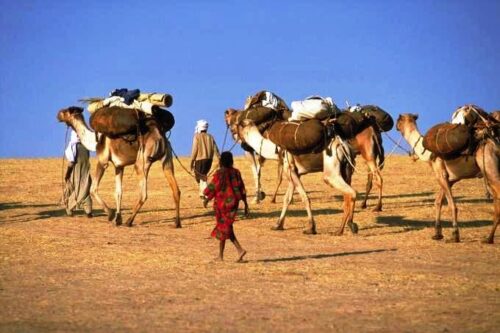

A herder taking care of cows is clearly different from an aristocrat who owns those cows (nomadism and cattle breeding are among the elements of Peul identity) and both are different from a merchant. Speaking of different Peul groups as a whole is therefore correct but limiting. The diverse groups are adapting to the local conditions and in some way centuries-old customs are changing. As an example, in the last years in Central Africa Peul herders were forced to sell their livestock (to pay ransoms and the extortions they were subjected to) and become cattle dealers due to insecurity in their area.

There are common phenomena in West and Central Africa that influence at various levels and in diverse ways the life of this community. As an example, climate change and the growth of the population are having a deep impact on those African countries and are creating tensions between the different ethnic groups.

In many areas, Peuls are the target of recriminations and accusations. The real problem is that for parts of the public opinion of these countries – even those who are not affected by the quarrels between Peuls and other ethnic groups – all Peuls are jihadists. Extremist organizations (in some cases led by Peuls) are trying to exploit the grievances of the members of this community to recruit them.

And it is difficult to distinguish between Peul militias that use weapons to enforce a jihadist agenda, and bands of Peul herders that use firearms to defend their interests in the increasingly violent clashes between them and farmers. It is worth noting that in some areas, such as Central African Republic and Chad, Peuls are even chased by other groups

of herders (like Arabs).

Climate changes

Climate change is considered one of the causes of the increasing violence between herders and farmers in West and Central Africa. The rise of temperatures and the diminution of rains in recent years led to the decrease of the land that is fit for pasture. These dynamics, among other things, caused an aggravation in the competition between herders and farmers for the use of land and sources of water.

According to some estimates, in the last fifty years in Western Africa the cultivated land increased by 50%.

This caused the reduction in the corridors used by Peul herders during the transhumance, since farmers started to widen their plots without asking the permission or even informing Peul cattle breeders. The land sharing agreements reached between the communities became irrelevant and the conciliation more difficult.

This is not a new phenomenon. According to the French historian Bernard Lugan, due to the desertification Peul herders started to move southward and westward from the Sahara area 4,000 years ago. What is happening today is therefore a consequence of a dynamic that started centuries ago and that passed through distinct phases in the years. As an example, there were periods of drought interspersed with moments of ‘normal’ rainfall. The quarrels between herders and farmers took place also in the past, and in some cases led to clashes. After those clashes usually an agreement was reached, or a new status quo was created. What is different is the level of violence observed, due especially to the proliferation of firearms.

According to the witness it is now normal to see a Peul herder moving from place to place equipped not only with a stick but also with a Kalashnikov. Firearms are widespread between both nomads and settlers. And most of all, between bandits that are one of the causes of the cycle of violence. Some firearms are produced locally in African countries (as an example, in Ghana) and then sold in the region. Others come from outside Africa and are sold through illicit networks, while some are stolen from arsenals of security forces.

Due to the increase of violence in crimes against them (cattle theft, kidnapping, robbery, etc.), nomadic Peuls started to bring these weapons with them, also inspired by their warrior traditions. But those firearms can also be used in disputes with farmers, together with bladed weapons and sticks or stones, the weapons of the past (as well as the present). But the farmers started to reciprocate with the same level of violence, when possible. And they sometimes can rely on the help of security forces, security forces that are not able to stop the illegal flow of arms. In some cases, soldiers or police officers even sell firearms illegally.

These dynamics are the consequences more of demography than climate change. It is how peoples react to the changes of weather that can bring changes to customs, or to confrontation and violence. As seen before, in the past competing groups found diverse ways to coexist in the same territory. Therefore, it is possible for the people involved to find a new way of living together. This must not be taken for granted, since a social fabric can be torn apart by violence. I.P.