Burkina Faso, Mali e Niger: the New Military Alliance in the Sahel.

The military juntas of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have signed the Liptako-Gourma Charter, establishing the Alliance of Sahel States (AES). The objective is to establish an architecture of collective defence and mutual assistance against common challenges. The unknowns.

On 16 September Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger signed an agreement by signing the Liptako-Gourma Charter in the region of the same name called the ‘three border area’, which is one of the epicentres of the security problems of the three countries. This agreement in Article 1 establishes ‘the Alliance of Sahel States and an architecture of collective defence and mutual assistance’ (art.2).The name itself indicates a broad projection and underlines the desire to potentially extend participation to those States that will embrace its aims.

The President of the military junta in power in Mali announced the signing on his X profile (formerly Twitter) citing the importance of the agreement for the security and well-being of the people of the signatory countries. The alliance could change the balance of power in the region, uniting countries with different problems but presenting similar vulnerabilities, and providing an alternative to the influence of ECOWAS and the Euro-Atlantic powers.

What is foreseen in the Charter

The Liptako-Gourma Charter is based on 17 points and focuses mainly on mutual assistance, the restoration of security and the prevention of rebellions. Article 4 establishes that Member States ‘undertake to fight against terrorism in all its forms and against organized crime in the common space of the Alliance’ while Article 5 announces that members will work to prevent, manage, and resolve any armed rebellion or other threat to the territorial integrity and sovereignty of each of the Alliance countries, giving priority to peaceful and diplomatic means but also with the use of force. Under Article 6, which is similar to NATO Article 5, ‘any attack on the sovereignty and territorial integrity of one or more Contracting Parties shall be considered an aggression

against the other Parties’.

The ruling military leaders, from the left: Capt Ibrahim Traoré (Burkina Faso) Colonel Assimi Goita (Mali) General Abdourahmane Tchiani (Niger).

Article 8 instead announces the commitment not to resort to ‘the threat, use of force or aggression, against the territorial integrity or independence of one of the member states; not to implement naval, road, maritime or strategic infrastructure blockades through the armed forces; not to perpetrate attacks or aggression against another Member State or third States, starting from the territory made available by one of the signatory States’.

An alliance that is opposed not only to the intervention of external countries in the territories of sovereign states but also to economic warfare tactics such as sanctions, which, however, provides for intervention in each other’s territories to fight insurrections. Article 10 of the Charter specifies that the financing of the Alliance of Sahel States will be provided mainly by the three signatory countries and Article 11 opens up membership to other countries.

Objectives of the Alliance

“This alliance will be a combination of military and economic efforts between the three countries”, Malian Foreign Minister Abdoulaye Diop told reporters. “Our priority is the fight against terrorism in the three countries”. Although it is not certain that the Armed Forces of the three member countries of this new tripartite alliance will actually follow the mutual provision of support, its formalization deepens the political and security bond and coordination in the fight against insurrections, the main concern of the contracting parties. The Alliance therefore has a triple function, which in order of priority are: coordinating efforts against insurrectional movements; weakening the political-diplomatic weight of the neighbours of the West African Economic Community (ECOWAS); and countering Western influences in the region.

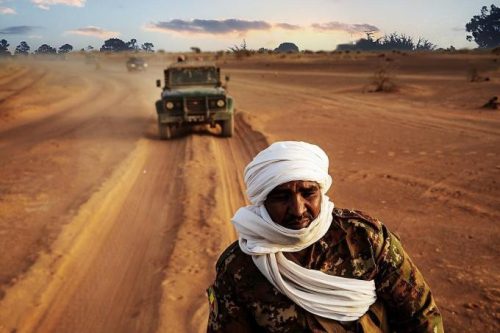

Nigerien army soldiers from the 322nd Parachute Regiment. File swm

Mali’s coup junta is experiencing a resumption of hostilities, after the start of the withdrawal of the MINUSMA peacekeeping mission at the end of August, with the pro-independence Tuareg (or kel tamasheq) of the Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA) advancing to the north against the Armed Forces and the Wagner group. This seems to be Bamako’s main concern at the moment. However, the penetration of Islamist groups such as Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in the Sahel (IS Sahel) is also constant, despite the fact that they are driven by mutual rivalries. These groups now have substantial freedom of movement thanks to the end of the peacekeeping mission and the French presence, especially in Liptako-Gourma, where the agreement was symbolically signed.

Fragmentation and the search for sovereignty

After the failure of the G5 Sahel military alliance (made up of the countries that are part of the new alliance with Mauritania and Chad and sponsored by France) this umpteenth agreement, defined as ‘the NATO of the Sahel’, presents many unknowns relating to its effectiveness, above all due to the military weakness of member countries. However, the signing can currently be considered both a diplomatic and internal success for the coup plotters. After capitalizing on the perception of corruption and impunity of supported governments of European countries, the councils have now signed a mutual and equal regional security agreement that highlights common objectives.

The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) convoy led by the Malian Armed Forces (FAMA). MINUSMA is to cease to operate by 31 December 2023. UN Photo/Harandane Dicko

But without addressing the causes of instability, increased militarization will only lead to more frequent violent clashes and new unpunished war crimes, which will spur the recruitment of separatists and jihadists. Only time will tell what the art. 3 of the Charter states, urging the establishment of bodies and operating mechanisms of the Alliance, will be carried out. There will be an answer at the time of the outcome of an intervention by one of the contractors alongside or within an allied country. A test case could already be that of the Tuareg independence activists in Mali, a more heated clash than the confrontation between ECOWAS and the Nigerian coup junta – which saw the mobilization of Burkina Faso. But, if this were the case, Niamey’s intervention in support of Bamako could likely exacerbate security problems in northern Niger, where other Tuareg populations are looking for greater autonomy. (Open Photo: file Swm)

Daniele Molteni/CgP