South Africa. The Energy Transition has to wait.

Beyond the government’s policy statements, the country will not start turning its back on fossil fuels in the short term. There is too much impact on employment.This has been confirmed by the Minister of Minerals and Energy Gwede Mantashe and supported by

the Trade Unions.

South Africa’s electricity generation accounts for more than 80% of the country’s output. It makes the country one of the top-20 emitters of carbon dioxide worldwide. The government plans that this will fall to 60% by 2030 through increasing renewable sources, extending the life of its one nuclear plant and natural gas.

About 95% of electricity production is controlled by the parastatal Eskom which is massively in debt and which has struggled to maintain a stable supply recently thanks to a legacy of mismanagement and corruption during the era of President Jacob Zuma. There are over 40,000 coal miners in the country and 28% of South Africa’s coal is exported, making it the 6th largest coal exporter in the world.

Electricians working on high voltage power lines. ©sunshineseeds/123RF.COM

Eskom also employs over 40,000 people. With an official unemployment rate of 34.9%, one can understand why the South African government is cautious about an energy transition.

To re-train 80,000 workers, many unskilled, would be a huge undertaking in a developing country. The governing party also needs their votes at a time when its popularity is on the decline.

South Africa is a world leader in the process of synthesising petrol and diesel from coal. Ironically this industry was first developed by the apartheid government at a time when the regime was threatened with oil sanctions. Today this very profitable company, SASOL, employs 30,000 people worldwide and is present in 33 countries. SASOL’s factory in Secunda, in Mpumalanga Province, in eastern South Africa, is estimated to be the largest single factory carbon polluter on the planet. Like all fossil fuel companies, it proclaims that it is going green, but progress is difficult. How to move away from fossil fuels and still run a profitable company, is the problem?

Gwede Mantashe, Minister of Minerals and Energy.

The recent funding from Western countries to help South Africa make the transition to a low-carbon economy has been received by the Minister of Minerals and energy, Gwede Mantashe with some scepticism if not downright suspicion. He argues that Western attempts to ‘help’ Africa to decarbonise are hypocritical because the West’s own record on decarbonisation is one of foot-dragging. He believes that South Africa and other African nations must maintain their sovereign right to use their fossil fuels and resist being railroaded into a hasty transition that harms African development goals. After all, the fossil fuel emissions of the African continent amount to a mere 3% of global emissions. Of course, South Africa supplies coal to some of the big polluters like India, so it depends on how you generate the statistics.

Minister Mantashe is an enthusiastic supporter of heavy industry, including nuclear power. He wants to maintain and expand the exploitation of fossil fuels in South and southern Africa. He recently directed his anger at environmental groups which brought effective legal challenges to Shell’s plans to conduct a seismic survey for fossil fuel deposits on the seabed along the West Coast of the country. His arguments have a certain force, and they resonate with the unions whose members’ jobs would be threatened by the transition.

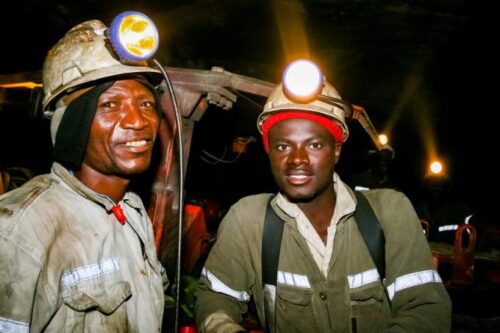

Underground Platinum Palladium Mining and Machinery. ©sunshineseeds/123RF.COM

There are two objections to them, however. The first is the problem of being left behind technologically. If South Africa and Africa invest in expensive infrastructure for the exploitation of coal and natural gas, this means there will be fewer resources to put into future energy. And this country and other African countries are ideally suited for some alternative energy sources. We have some of the most abundant sunlight sites in the world and many onshore and offshore sites which are suited to harvesting wind energy. True, these are being developed in South Africa, but mostly by private energy producers and at a government-regulated pace that is designed to protect the coal industry.

We are in a similar position to twenty years ago when the government decided to build two massive power stations in South Africa’s coalfields, thus locking the country’s economy into a technology that was already out of date. Minister Mantashe seems happy to lock us into coal and gas for another 30 years by which time Western nations might well be imposing punitive taxes on goods produced and transported

using fossil fuels.

Open pit coal mining and processing in South Africa. 123RF.COM

The second problem is illustrated by the situation in Cabo Delgado in Mozambique where the curse of the hydrocarbon resource is being played out tragically in the violence which has gripped that area. Islamist insurgents have caused havoc among local people in the struggle to take control of the Total gas fields off the coast.

Developing countries with ‘get-rich-quick’ natural resources are prime targets for criminal groups. It is not just the problem of insurgency. In Angola, the entire oil industry became the fiefdom of a single political family. The sad fact is that possessing large deposits of hydrocarbons does not automatically translate into the equitable sharing of wealth. The history of South Africa itself illustrates this fact – the diamonds and the gold discovered in the 19th century attracted the attention of empire-builders like Cecil Rhodes and other colonial looters.

Perhaps South Africa has the legal and institutional strength to avoid the problem of the resource curse. However, the fact that Shell has been conducting a seismic survey off the East Coast (and another has been planned by an Australian company off the West Coast) has set environmental alarm bells ringing.

Oil rig in the ocean bay of Cape Town. 123RF.COM

A solid historical objection to Shell is the company’s history in Ogoniland in Nigeria where the environmental impact has been catastrophic and scandalous. If they trashed Ogoniland, one can ask, how can we guarantee that they will not also trash the coast of the Eastern Cape, known locally as the Wild Coast for its great beauty and rich ecological diversity?What is the feeling of ordinary people about the issue of the energy transition? In the areas where drilling might take place, there is concern for the loss of traditional economies connected to the environment, as well as the impact on tourism. Solidarity is not 100%, of course, for there are always some who would hope to benefit from the concessions and contracts that hydrocarbon exploitation brings.

As for people who are not directly involved, there seems little concern except among the professional classes. For many ordinary people, life is a hard struggle and therefore issues like how rapidly we move to a renewable electricity supply are hardly their daily concern. For them, the question is whether they can afford electricity at all and whether their children will ever find jobs. Unlike in Europe where the supporters of fossil fuels are on the defensive, in South Africa, fossil fuel businesses and their political supporters still hold many of the strong cards. (Open Photo: The Tutuka Power Station near Standerton, in the Mpumalanga Province. ©dpreezg/123RF.COM)

Chris Chatteris sj