South Africa. Joburg. Towards Social and Urban Renewal.

Johannesburg or Joburg, as it is called, is one of the fifty largest cities in the world. With six million inhabitants, it is estimated that in less than a decade, it will be a mega-city and will have to find solutions to the demands of services and basic resources.

Known as Igoli (city of gold, in Zulu), the urbanization of Joburg began after the discovery of deposits of the precious mineral in 1896. Only 35 years later it already had 400,000 inhabitants. It is also the city with the largest area of trees planted in the world (6 million).

Its population is made up of 76.4% blacks, 5.6% mestizos, 12.3% whites and 4.9% citizens of Hindu origin. Furthermore, according to official data, 7% of its population is illiterate and 34% only received primary education. It is also a mix of religions: 53% are Christian and 24% do not identify with any creed, 14% follow independent African churches, 3% are Muslim, 1% Jewish and 1% are Hindu. It also has a small community

of Mormons. (49,000).

Despite the push that the country’s democratic governments, the first led by Nelson Mandela, gave to the construction of social housing – between 1994 and 2014, 2.9 million homes were built across the country as part of the Reconstruction and Development Project – and the increase in infrastructure for basic services for the population that suffered under apartheid discrimination, the situation is still serious.

Almost 30 years after the end of apartheid, the feeling of stagnation, coupled with the frustration of repeated promises and an average waiting time of decades for access to a home, indicate that the problem is still far from being solved.

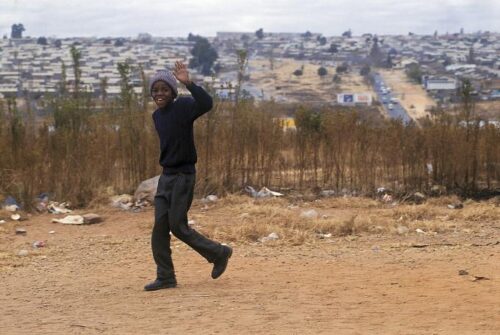

A boy on the outskirts of Johannesburg

According to World Population Review, 80% of the South African population resides in formal housing, 13.6% in informal housing and 5.5% in traditional housing. In the case of Johannesburg, it is estimated that 29% of its residents live in informal housing, with limited access to water and electricity, and poor sanitation.

“We strongly believe in the importance of undoing the divisions of space imposed by the apartheid era that continues to segregate our cities on the basis of race and social class. And for this, integrated housing districts from the periphery must be developed, with economic and leisure opportunities for the districts of the city centre”, says one of the managers of Divercity, a real estate fund formed by large private companies in the sector (Atterbury, Ithemba, RMB, Future Growth and Nedbank Properties) which is collaborating with the Johannesburg city council to make inhabitable those areas of the city condemned to service cuts or occupied by criminal gangs who demand money from people and keep them under coercion and violence.

From Hillbrow to Maboneng

“Joburg is rapidly becoming urbanized and is expected to become a megacity by 2030, requiring more homes to meet current and future demand. Converting the old commercial buildings in the city centre into affordable residential housing with a high standard of quality in the urban core helps to answer this question economically”, emphasises the Divercity manager in his brand-new office in one of the restored buildings in Maboneng, located in the area christened Jewel City, whose splendour cannot be ignored.

The main square of Jewel City. Photo José Luis Silván Sen

Jewel City is just a street where transformation is absolute. Modern buildings decorated in bright colours converge in squares where children can play safely. You can see international and local fast-food restaurants, well-stocked supermarkets, and modern cafes with a wide variety of products. It is a scene limited to a specific space because in parallel streets you pass into a completely different situation, with badly paved roads and overcrowded and untidy places.

The restored buildings function because all their services, from waste collection to water and electricity supply, to security, are private. The well-intentioned former mayor Herman Mashaba launched a plan in 2016 (with an initial investment of around 1,220 million euros) to ‘rebuild Joburg’ which included kilometres of cycle paths, whose durable green colour can be seen in some streets in the neighbourhood of Hillbrow, and partnering with real estate companies to offer affordable one- to three-bedroom apartments to the lower-middle-class population. This is with rents of 55 to 275 euros, depending on the number of rooms, excluding the services necessary to make them habitable such as water and electricity.

The entrance to renovated buildings with a security system. Photo José Luis Silván Sen

Mashaba, during his tenure – he resigned in 2019 to form a new political party, Action SA, with which he ran for local election in November 2021, without obtaining a majority that would allow him to carry out his project – estimated that more than 150,000 people were on a waiting list for accommodation and an average of 3,000 migrants arrived in Johannesburg each month in search of better economic opportunities to build a decent future.

Newtown and culture

In addition to basic accommodation at an affordable price and with guaranteed minimum services, other areas of the city centre have undergone a somewhat fictitious transformation, due to specific places such as Newtown, which is home to Mary Fitzgerald Square, where events and political meetings are usually organized. The dilapidated Museum Africa and the Market Theatre, which with its experimental shows and shows that end late in the night, provided a degree of big-city normality, aside from the obsessive safety in which every citizen moves around Joburg.

During the Mashaba period, the number of police officers on the streets was increased to make the city centre ‘the safest place to invest’. The claim remained only words since crime rates and violent deaths have not stopped rising.

Buildings undergoing renovation. Photo José Luis Silván Sen

Farther south, between Market and Commissioner Street, in Gandhi Square and the Marshalltown business area, the spaces designed to sit and enjoy the hustle and bustle of the city are surprising. As in Maboneng, it is impressive that if you widen a little the radius in which you walk, you come to a road with potholes and sidewalks where the sewer covers are missing. The feeling of insecurity also increases, and is impossible to avoid when faced with evidence of the armed guards at the entrances to buildings who warn people of the danger of carrying a mobile phone in one’s hand.

Fighting the structural inequality that exists throughout South Africa, but which in big cities like Johannesburg increases due to the presence of mafias and corruption that has become intrinsic in recent decades, is the great challenge of the mayor, Mpho Phalatse, who last January promised a ‘golden start’ for the city. This commitment includes the development of the city centre, the operation of traffic lights, public transport, road maintenance and the fight against cable theft to avoid power outages, and has also led to the renaming of the Joburg heritage site named after Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Much remains to be done for the city to become a more human place. (Open Photo: View of Johannesburg. Photo José Luis Silván Sen)

Carla Fibla Garcia-Sala