The churches. Lost engagement.

They have lost the prophetic voice they had in the days of apartheid. They have no longer been able to effectively guide the action of politics. Too many gaps to bridge.

The death of Archbishop Desmond Tutu on St Stephens Day 2021, occasioned many reflections on his public witness, his prophetic leadership in the anti-apartheid struggle and his pastoral discernment in leading the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in those early years after the advent of democracy, as South Africa sought to find its bearings in a post struggle reality.

He remained till his death, the moral compass of the nation, a fearless articulator of truth to power and as many observed, he was as critical of the pathologies of the democratic government as he was of the apartheid regime, a stalwart in crafting a theology of repentance and forgiveness and a citizen of the world. His solidarity with oppressed people everywhere was one of his traits. We saw it in his closeness to the Rohingya people and the Palestinians. He was a man of prayer and of deep spirituality. In so many ways his witness as it has been recalled and lauded over these past months, also constitutes the ongoing challenge to the broader faith communities and to the Christian family in particular. It also stands, twenty-six years into democracy, as a benchmark for the success of the church’s engagement with our context.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu (centre) leads some 30 clergymen through Johannesburg to police headquarters in 1985 to hand in a petition calling for the release of political detainees.

Twenty-six years is obviously not long enough to measure the church’s contribution to the reversal of the injustices and inequalities of a system that was rightly called a crime against humanity. The very fact that corruption has robbed this country in recent years of a trillion rand of public money – a theft from the poor – that poverty remains as a wound on our body politic and that unemployment affects over 36% of the population, that schools are dysfunctional and that we minister in unchanged apartheid defined spaces, all means categorically, that to an important degree, we as the moral compass of the nation, as the prophetic voice in the midst of abhorrent situations, have not raised our voices loudly enough to give politicians and business concerns who grow rich off low wages and exploitative practices, reason to change their ways. They have not felt challenged enough or morally chastised by the faith communities’ ministry of standing with the poor and naming social sin, to change their ways. That must spell a failure on our part.

It is true that the faith communities have been good about raising red flags, about drawing attention to the multiple wrongs in our country.

It is true that in times of dire need the faith communities have responded with charitable care.

We saw it in the hard times of the pandemic. That this is true is shown by the activities at levels that generally make for social change, namely, education in its broad sense, advocacy and activism. There have been good examples at different times over the past years – and those have been stellar moments – of marching, of standing in solidarity, of advocacy around critical issues. But it seems that those moments have remained moments. As faith communities, as churches, it seems we still need to find a coherent overall understanding of justice issues that allows us to analyse and act coherently, that allows for larger buy-in from those who fill our pews and that is so persuasive that we understand that these words from the Final Message of the Synod of Catholic Bishops of 1971 saying that ‘working for justice is a constituent element of preaching the gospel,’ is something that applies to all. It seems that we are content, as in the apartheid era, to leave the work for justice to a few. We are also challenged by Archbishop Tutu’s testimony to see that all injustice is part of a whole. Abuse and domestic violence, xenophobic utterances, poverty, just wages; all these issues belong together and as long as we separate them out, we rob them of their force and their potential to touch some areas of our lives, and thus we find it easy to absolve ourselves from responsibility for righting our wrongs. It might also be that the church and faith communities’ own complicity in race and class exploitation, in cultures of abuse and elitism, finds it harder to call others out while vestiges of its own

sins are still evident.

Stellenbosch. Altar girls from church with a cross in Kayamandi township©dvsakharov/123RF.COM

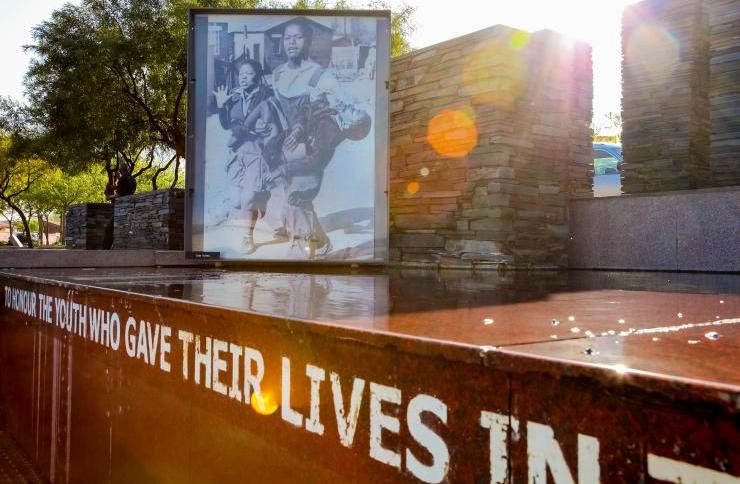

Archbishop Tutu once said that the church is a slumbering giant and sometimes it wakes from its slumbers and growls a little. Possibly the positive point in its growls is that the small noises and acts might acquire the power to take on greater potency as the world and our country’s outlook gets bleaker. It is possible that the best the church can do is to amplify the growls till they become a deafening noise. History has shown that such incremental moments and actions can indeed change the tide of history. It might well be that the church cannot become a home for all until it, with others, has put the effort in to transform the myriad of structures that keep people apart and perpetrate injustice and only then will spaces of worship become homes to all, communities of justice, witnesses to hope and examples of peace. It is a dream and one that we strive to achieve but it is still a long way off. (Open Photo: Outside Hector Pieterson Memorial Museum in Soweto Johannesburg. ©sunshineseeds/123RF.COM)

Peter-John Pearson