Narrative African Voices in Print and on the Web.

A panorama of the newspapers founded by African intellectuals who gave and are still giving a black tone to cultural and literary production.

To change the narrative on Africa, it is necessary to have spaces where this narrative can be initiated. Unique and original spaces. Original spaces that emerge from autochthonous roots. These places, whether physical or virtual, exist in the continent, and some have been there for some time. There are newspapers but also literary experiments, places of cultural aggregation and exchanges of perspective. Founded and fed by African intellectuals.

Many are from the diaspora, working to hold together the various threads of pan Africanism or simply to internationalise African voices. Many others never left Africa.

There are many Intellectual African magazines that already attracted notice in the fifties and sixties when all efforts and attention were everywhere focused on the struggle for independence.

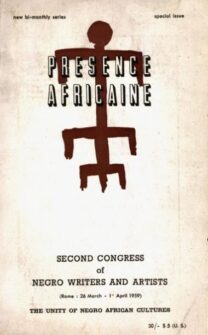

One of these is Présence Africaine founded in 1947 by Senegalese Alioune Diop, who studied in Algeria and at the Sorbonne in Paris, becoming a Professor of Letters.

The magazine became a sort of forum for a movement that, first of all, promoted a concept that was, at the same time, a field of intellectual, cultural and political action: negritude. And it succeeded in involving the French and African intelligentsia of the time: from Paul Rivet to Jean-Paul Sartre, from Albert Camus to Aimé Césaire.

Concerning Présence Africaine and its founder, the Cameroonian author Mongo Beti, the pseudonym of Alexandre Biyidi Awala, once said: “Alioune Diop will go down in history as the one who allowed the blacks to express themselves. Without this instrument forged by him, we would have remained as we always were: silent”.

The magazine – that has already been available online for some time – since the death of Diop (1980) has been headed by his wife Christiane Yandé Diop who has continued to sustain the voice and black literary expression liberated from the exoticism into which Western culture often relegated it. Reading clubs, interviews with authors, as well as editorial houses, thrive. It is a shame that there are still so few associated bookshops in African territory (Présence Africaine has its physical seat in Paris) where books edited by the editorial houses are distributed.

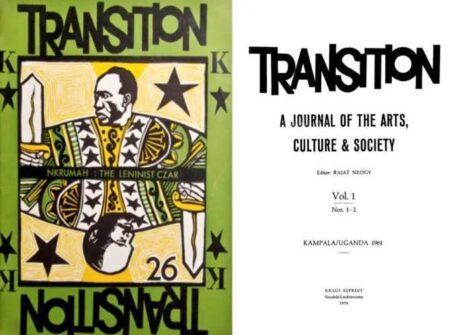

Then there was Transition founded in 1961 as a ‘Newspaper of Arts, Culture and Society’ by Ugandan Rajat Neogy. Among the contributors (and well-known voices) to the magazine were Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, and James Baldwin. Neogy was arrested in 1968 for sedition after publishing an article critical of the Ugandan government. Nevertheless, the magazine did not disappear; on the contrary, it assumed a growing international character. Today it is a publication of the Hutchins Centre of Harvard University – which also includes many research institutes, one of which is the W.E.B. Du Bois Research Institute – with Wole Soyinka as head of the editorial team and the Anglo-Ghanaian philosopher and author Kwame Anthony Appiah as co-editor. An incredible amount of study and research material has been accumulated on its website.

New seeds

All of these initiatives appeared in their time as milestones and could not, therefore, be abandoned. On the contrary, they sprouted and flowered on a thousand branches. Then came the Internet and the desire emerged – also the urgency – to scatter new seeds. One of the first online platforms for literature, art, and politics as narrated from within, Chimurenga is a pan-African platform of writing, art, and politics founded by Ntone Edjabe in 2002. Drawing together a myriad of voices from across Africa and the diaspora, Chimurenga takes many forms, operating as an innovative platform for free ideas and political reflection about Africa by Africans.

Outputs include a journal of culture, art, and politics of the same name (Chimurenga Magazine); a quarterly broadsheet called The Chronic; the Chimurenga Library – an ongoing invention into knowledge production and the archive that seeks to re-imagine the library; the African Cities Reader – a biennial publication of urban life, Africa-style; and the Pan African Space Station (PASS) – an online radio station and pop-up studio.

The aim of its many and multi-form activities “is not just to produce new knowledge but rather to express the intensity of our world, capture those forces, and act”.

The literature and poetry sites have for some time been helping to make known a culture that still remains unexplored given its vastness, or rather, a bottomless well. Brittle Paper is one of these, for those who love and are never satisfied with African literature and its diversity. More territorially centred is Bakwa, a Cameroonian literary magazine on Anglophone literature in a country with a Francophone majority (and where, as a consequence, a civil war has been waged since) and dominated by the French language.

Doek! is instead a Namibian literary magazine – but is also contains visual poetry and arts – co-founded in 2019 by Rémy Ngamije. It is a place where the heritage of colonialism and the “the unexpressed losses due to the liberation struggle” against the white government of South Africa, are explored.

Other initiatives worthy of mention are the Johannesburg Review of Books which gives a voice to African writers to comment on literary works from all over the world, but especially those from Africa. One of the spaces opened up for writers of short stories (including emerging ones) who live in the continent or are part of the diaspora is Afreada, a natural fusion of Africa and the reader. The aim of this platform inaugurated in December 2015 is to preserve those cultures and traditions that find expression in the stories published on the Website.

Another magazine founded during the same period and based in Nairobi is Jalada, a collective of pan African writers which has already made history and among its projects is the translation of The upright revolution: or why humans walk upright, by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o into 97 languages, most of them African. Finally – simply because it is the youngest in this incomplete barrow load – Lolwe, an online magazine that publishes stories, book reviews, personal articles, photographs, and poetry, was founded in 2020 by the Kenyan editor, writer, and lawyer Troy Onyango. The name of this project derives from Nam Lolwe, the original or traditional name for Lake Victoria which means ‘infinite lake’. Similarly, Lolwe means ‘infinite’, ‘without limit’, like the flow that unites the narrating voices of the African continent.

Antonella Sinopoli