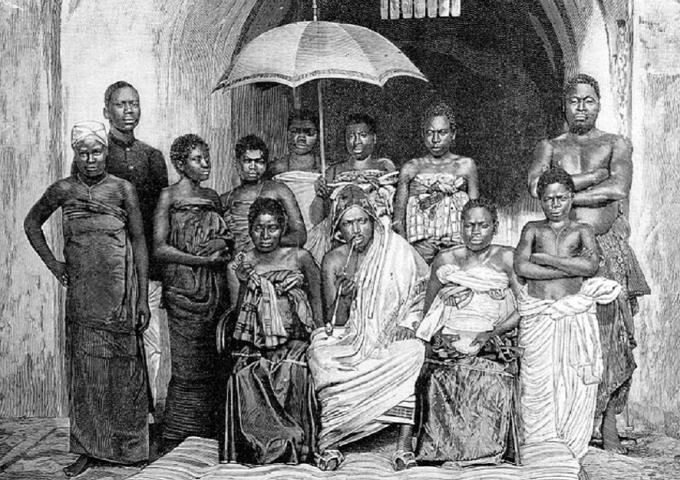

Between 1600 and 1900 the city of Abomey was the pride of the kingdom of Dahomey (today’s Benin). Court art developed there, in which genius, talent, and inspiration served above all to exalt the figure of the king.

Dahomey, also known as the kingdom of Abomey, after the capital, occupied the south-central part of what is now Benin. Founded in 1625 by the Fon ethnic group, it lasted until November 1892 when Gbéhanzin, the last king, was defeated by French colonial forces.

The solidity of the kingdom of Adomey, its social and political organization and the richness of its culture made it one of the most famous realities of the Gulf of Guinea. From the frescoes to the tapestries celebrating the war exploits of the sovereigns, the art of the palace in Abomey was an exceptional witness to the history of the kingdom which nourished and enlivened it.

Royal statues from Benin’s historic Kingdom of Dahomey. Quai Branly museum in Paris.

If in other kingdoms it was the griots, or official narrators, who praised the feats of the kings, in Abomey this task fell to the court artists. In this they can be considered authentic ‘oral historians’, as they created allegorical figures that transmitted messages intended to impress the visitor to the palace, to be disseminated throughout the kingdom and to intimidate enemies on the battlefield.

Each object was made by a family of artists, whose knowledge was passed down from father to son, and was ‘signed’.

From the foundation of Abomey to its fall, 15 kings succeeded each other on the throne and all, with no exceptions, surrounded themselves with artists of different origins: Yoruba, Fon, Mahi, Haussa. Once the genius and talent of an artist were recognized by the king, he then hurried to set up a workshop for him near the palace and to provide him with the materials for the work, helpers, some wives and a piece of land to cultivate. This proximity to the royal palace facilitated contacts, more or less discreet, between the king and the artist for commissions of works to be created.

Half-man, half-fish statue (called bochio), Fon style. Provenance : Abomey, ancient kingdom of Dahomey. This statue would represent Béhanzin, the last king of Dahomey. Quai Branly museum in Paris.

The artist was known by the name of adawunzowato (Fon language: ‘one who makes beautiful works’) and was believed to be ‘possessed’ by Aziza, the spirit responsible for creation. However, although he enjoyed great freedom in the execution of his work, once he became court, he was subservient to the monarchy: each of his works – bas-relief, tapestry or sculpture – was intended to glorify the king.

He never resorted to a real portrait. The representations of the monarchs did not have human form, but rather alluded to the animal world since, according to tradition, the Abomey dynasty descended from Agassou, the son that Princess Aligbonon, daughter of the king of Tado, had given birth to after being fertilized by a leopard.

Showcase of the Kingdom

From the time of Aho Houégbadja, believed to be the true founder of the kingdom of Abomey (actually, he was the third king and reigned from 1645 to 1685), up to the reign of Agoli-Agbo (1894-1900), as many as 10 royal palaces were built. Of these, only those of King Guézo (1818-1958) and King Glèlè (1858-1889) remain, which since 1944 have become the headquarters of the Abomey Historical Museum. Authentic ‘kingdoms within the kingdom’, the royal palaces were forts, universes jealously protected from prying eyes and from enemy attacks. Centres of political life, they embodied both the power and stability of the kingdom and its immutable and sacred character. Emblematic in this regard are the access doors to the adjalala (the reception hall) of King Glèlè. Sculpted by the Sossa Dede family, they depict elephants, horses, dogs, rifles, sabres, eyes, and toads – symbols of the strength, safety and peace that characterized the kingdom.

A wooden door from the king’s palace Gele of the Dahomey kingdom, dated 19th century, displayed at Quai Branly museum in Paris, France

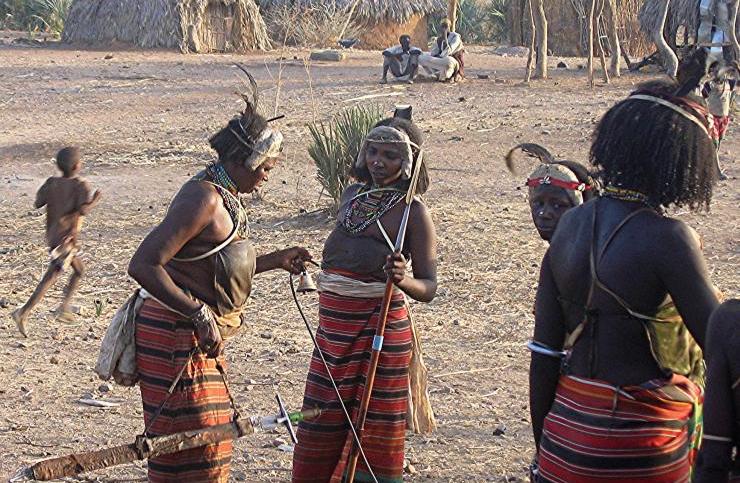

Even the walls of Abomey’s buildings have stories to tell. The facades are adorned with magnificent earthenware bas-reliefs, authentic visual chronicles of Dahomey. The technique is that of sunken relief: the artists carved out a square or rectangular niche in a very thick wall inside which they modelled the desired shape with clay. Once completed, this assumed the appearance of a half-round figure, protected from the rain and perfectly integrated into the structure. Works mostly by artists of the Houndo and Assobakpé families contain all the memory of the Dahomean dynasty and today offer it to the enchanted eye of the visitor. One can admire the silhouette of a buffalo, the emblem of King Guézo, proud to equate his strength to that of the mighty animal, or of a lion, as a disguised message from King Glèlè to enemies intending to attack his kingdom.But the genius of the artists is best seen in the creation of some hieroglyph-like signs. In them we distinguish the furious Amazons (women who formed the army of Dahomey) and war trophies, such as chameleons brandishing a sword or pine cones coming out of the sun. They are probably well-known graphically depicted proverbs, full of political and moralizing messages.

Chronicles on cloth

Tapestries were widely used in the Abomey kingdom, first to make military maps, then to celebrate friendship or to convey the titles of kings.They were also used in religious centres and places of worship, where they served as skirts for voodoo adepts. The masters of tapestry art were members of the Hantan, Zinflou and Yémadjé families, who became famous for the technique used: they inserted pieces of cut-out fabric of different colours into a single-colour canvas, so as to allow the tapestry to be admired from both sides.

Fon banner from the Kingdom of Dahomey.

The results were amazing. It depicted scenes of war or the simple meaning of the king’s nickname. For the most part, the sovereign was exalted in an allegorical form: he was represented as a man out of the ordinary, capable of killing a buffalo by the horns or in the act of subduing enemies with weapons and handcuffing them. Salpata, the voodoo of smallpox, which sows death among the population, is on the scene in a tapestry. In another, against a black background, there are scenes of war between the Fon and the Yoruba. In a third, with a certain amount of macabre in some details, we see people defeated and torn apart, victims of the glorious army of the Amazons.

Unlike metalworking, tapestry-making was not a Dahomean art. It is thought to have been introduced during the reign of King Agadja (1711-1740), who captured two master craftsmen of the Hantan and Zinflou lineages in the Avrankou region, north of Porto-Novo.

Glory to the King

The term ‘regalia’ meant all the precious objects intended to glorify the sovereigns and court dignitaries. Chairs and thrones, batons, decorations, musical instruments, sandals, caps and fans. Nothing escaped the cult of appearances.

Also exceptional is the statue of the god Gou, made by Ekplékendo Akati, a prisoner of war and certainly an adept of Gou. Life sized, the figure appears dressed in a soldier’s tunic and wears a hat, resembling an asen (portable altar), which allows him to receive libations and sacrifices.Combining human and animal forms, the court artists of King Guézo and King Glélé sculpted statues depicting the moral and physical qualities attributed to their rulers. Placed in front of troops during battles, these effigies also served as a bogeyman against enemies.

Benin Bronzes were taken from the ancient city in Nigeria by the British army. British Museum

Very well-known is the asen of king Gbéhanzin, made by Vincent Lanmandoucelo Aissi, of the Hountondji family: it represents the meaning of the name of the last king, Gbéhanzin, (‘the universe has the egg that the earth desires’): it alludes to fragility of the kingdom and the diplomacy with which a king must reign. Also beautiful are the royal drums, the akatahounto, specialties of the well-known families of artists Houeglo, Djotohou and Hountonvo.

Artists also worked for court dignitaries (especially the prime minister) and soldiers (the Amazons). Owning works from royal workshops was a privilege. The king’s soothsayers also used tools prepared by the court artists. The polychrome trays and ivory hammers carved by a Yoruba craftsman, of the Houndo family, for the soothsayer Guedegbe are beautiful. On the edge of the tray, the face of a legba (intermediary between gods and men) is reproduced 16 times. 16 is a magical figure: in addition to being quadruple of 4, multiplied by itself it gives 256, which is the number of ‘signs of divination’ (fa), which collect all the myths and traditional knowledge.

The Return of the Treasures of Abomey

The history of the ‘Treasures of Abomey’ is as dramatic as their sculpted forms. In November 1892, the French general Alfred Amédée Dodds entered Abomey, the capital of the Danxomè kingdom, after two years of ruthless warfare. French troops sacked the palaces and the city. Dodds and his troops seized important royal objects, including the 26 artefacts that Dodds donated to the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris in the 1890s. Since the 2000s, the objects have been kept at the Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac.

Over the years, the Benin government demanded the return of the items. Only in 2016 did France admit that the Beninese government’s request for President Patrice Talon was legitimate, although restitution remained legally impossible under French property law. In November 2017, President Emmanuel Macron affirmed in his speech at the University of Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) the French willingness to undertake restitutions. The return process finally began.

On December 24, 2020, the law relating to the restitution of 26 cultural assets to Benin was promulgated in France, in derogation from the principle of inalienability of French public collections. On November 9, 2021, the deed of physical transfer of ownership of these 26 assets to the Republic of Benin by the French Republic was signed at the Elysee Palace, in the presence of President Patrice Talon and President Emmanuel Macron. The following day, the 26 works of the royal treasury of Abomey were transported to Cotonou. It took 130 years for the Abomey Treasury to be returned to the homeland. (Open Photo:King Behanzin of Dahomey and his household. New World Encyclopedia.)

Flavien Amouro