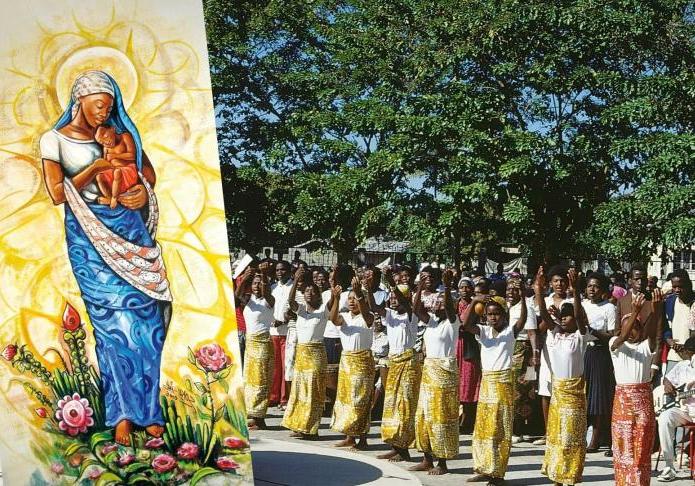

Marian Shrines in Africa. The Great Devotion.

Many shrines and pilgrimage sites in honour of the Virgin Mary have sprung up throughout the African continent. Seven cases of Marian apparitions have been reported, the most famous and officially recognised is that of Kibeho in Rwanda. An introduction to the main centres of Marian worship in Africa.

To date, seven cases of Marian apparitions in Africa have been reported: in 1980 in Ede-Oballa (Nigeria); in 1982 in Kibeho (Rwanda); in 1984 in Mushasa (Burundi); in 1984 again in Rwanda, in Mubuga; in 1985 in Yagma and Louda (Burkina Faso); in 1987 in Muleva (Mozambique); and in 1998 in Tseviè (Togo).

There are few testimonies about these appearances, except for those that took place in Kibeho, a small town in south Rwanda, which were officially recognised and which received canonical approval by the Holy See, on 29 June 2001, after Augustin Misago, the Bishop of Gikongoro, approved public devotion linked to the apparitions that took place in the small town of Kibeho between 1981 and 1983. He recognised as authentic the testimonies of the three visionaries Alphonsine Mumureke, Nathalie Mukamazimpaka and Marie Claire Mukangango, who were 16, 17 and 21 years old, respectively. The Virgin Mary appeared to them dedicated as ‘Nynia wa Jambo’, meaning ‘Mother of the Word’.

Rwanda. Sanctuary of Our Lady of Kibeho. The only approved Marian apparition in Africa. (CAN)

The three girls said that the colour of her skin was black. The Virgin invited them to conversion, prayer and fasting. Once, on 15 August 1982, the Virgin showed them gruesome scenes: “A river of blood, massacres, corpses lying abandoned”. It was the announcement of what would happen in 1994, a genocide with almost a million dead.

In the meantime, Kibeho has become a place of interest as a pilgrimage destination. The Kibeho shrine is dedicated to Our Lady of Sorrows. Rwandans consider it a pilgrimage destination and meeting point for those who seek God and wish to pray. According to the Rwandan bishops, “Kibeho is a place of conversion, of reconciliation and reparation for the sins of the world; a meeting point for those who were lost, for those who are passionate about the values of compassion and brotherhood without borders. For this reason, the Church must become a place of reconciliation for all. Our Lady has come to speak to her young children to begin the second phase of evangelization, at the end of the second millennium and at the beginning of the third”.

Burkina Faso. The Yagma shrine is dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes.

In 1966, the then Archbishop of Ouagadougou, in Burkina Faso, Cardinal Paul Cardinal Zoungrana, urged Christians who wanted a place to worship Mary: “Find the place you like, prepare it and then we will come to build a church”. Therefore, the site of Yagma, a few miles from Ouagadougou, was especially chosen in 1967 for the purpose of building a Marian shrine. On that small hill a replica of the Lourdes grotto was built out of lateritic stone. The site of Yagma hosted the first pilgrimage in 1968 and in 1971 the place was officially recognised by Cardinal Zoungrana as a pilgrimage destination. In 1985 a young woman claimed that the Virgin had appeared to her several times, although these appearances were never officially confirmed by the ecclesiastical hierarchy, the number of pilgrims has been constantly increasing. Twenty-nine January 1990

was a historical day.

The site of Yagma welcomed Pope John Paul II that day. More than 600,000 people attended the Eucharist, as the Pope blessed an image of Our Lady of Lourdes that he gave as a gift for the site of Yagma.

Other Marian places are Our Lady in the town of Dingasso, in Bobo-Diulaso; Our Lady of Peace, in Diébougou; Our Lady of Louda, in Kaya; Our Lady of Reconciliation, in Koudougou; and Our Lady of Lake Bam,

in Ouahigouya.

The shrine of Notre Dame de la Délivrande (‘Our Lady of Salvation’) in the town of Popenguine, Senegal, was established in the 1800s by a Catholic bishop named Mathurin Picarda.

In May 1888, Monsignor Picarda, led the first Marian pilgrimage to the shrine in Popenguine. In 1891 a small stone basilica was built to replace the previous wooden one. In 1988 a new larger church with a greater capacity was inaugurated.

Senegal. The shrine of Notre Dame de la Délivrande (‘Our Lady of Salvation’) in the town of Popenguine. (Photo: Ji-Elle)

Since then, Popenguine has become a place of pilgrimage and Marian worship for Senegalese people. In 1991, at the request of Cardinal Hyacinthe Thiamdoum, a native of Popenguine, a new church was built and dedicated to the Immaculate Conception of the Most Holy Virgin Mary, and it was named a minor basilica in 1991. This marked the beginning of a new life for the church and the community.

On February 20, 1992, Pope John Paul II, paid a visit to the shrine and crowned the statue of Our Lady of Deliverance before a crowd of thousands of people. Since then, the sanctuary has been the destination of many pilgrims. Currently more than 100,000 people annually visit this great Senegalese Marian shrine.

The Marian shrines of Egypt, besides having a special importance for the memory of the historical presence of the Holy Family in this land, have always been of special interest from the ecumenical point of view. Some, among the 160 churches dedicated to the Virgin Mary in the country, are considered authentic ‘Marian places’ or real sanctuaries.

Among them are the monastery of Santa Catalina, in Sinai; the Cathedral of Our Lady of Egypt; the sanctuary of the Virgin of Zeitoun; the Al-Muallaka Church (‘the Hanging Church’), in the area of Al-Fustat in Cairo; and the Saint Mary Church, in Maadi. The Feast of the Assumption is one of the most popular feasts in Egypt. The faithful of Egypt’s Coptic Church simply call it the ‘feast’ of the Virgin. The fidelity with which the Coptic Church has venerated Mary has been unceasing. The icon of the Virgin found in the famous Al-Mou’allaqa church is highly revered. Saint Catherine’s Monastery is an Eastern Orthodox monastery located on the Sinai Peninsula, at the mouth of a gorge at the foot of Mount Sinai, near the town of Saint Catherine.

Cathedral of Our Lady of Egypt. CC BY-SA 3.0/ Hierarchicus

It is the most important Marian sanctuary in the Sinai Peninsula, and the traditional site of the Burning Bush, the symbol of the divine motherhood of Mary. The monastery is visited by thousands of pilgrims every year.

Despite the fact that there are not many important sanctuaries in Ethiopia, due to the little importance that the Coptic Church gives to images, the Virgin Mary, known as ‘Waladita Amlâk’, the Virgin Mother of God, has a very special place in the Ethiopian cult, and the devotion to her holds the highest place. Ethiopia is known as the country of Mary, its protectress. The name Mary is very common among Christians, both women and men, in Ethiopia, and many churches carved out of the rocks are dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

On the 10th of February the Ethiopian Church celebrates the feast of Our Lady of the Covenant of Mercy (Kidama Mehret). It refers to the Ethiopic tradition that Jesus promised his mother that he would forgive the sins of those who sought her intercession.

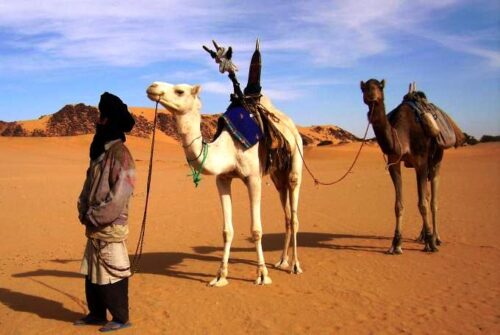

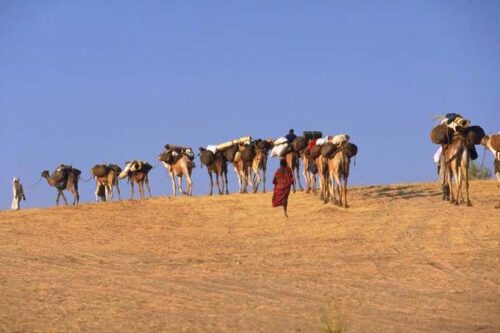

Every year in November, thousands of Malians and Christians from all over West Africa gather in the small town of Kita, about 150 kilometres west of Bamako, Mali’s capital. They go on pilgrimage to pay homage to Our Lady of Kita. The clay image of the Virgin Mother was made by a lay brother who collaborated with the first missionaries in the country.

The pilgrimages to venerate Our Lady of Kita began in 1970 and take place every year in the last week of November.

These events have always been moments of dialogue and brotherhood between Christians and Muslims in Mali.

Ivory Coast. The Basilica of Our Lady of Peace in Yamoussoukro, CC BY-SA 2.0/ Felix Krohn –

Located on the west coast of Africa, Ivory Coast was evangelized in the last decade of the 19th century. The Basilica of Our Lady of Peace in Yamoussoukro, the administrative capital of Ivory Coast, is considered the ‘Palace of Our Lady’. Consecrated by John Paul II in 1990, it is known as the ‘Saint Peter’s Basilica of Africa’. The design of the dome and encyclical plaza are clearly inspired by those of the Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican City, although it is not an outright replica. It is the largest church in the world. Every year thousands of pilgrims arrive in Yamoussoukro from all over the continent to venerate Our Lady of Peace.

However, the national Marian shrine in Africa is that of Our Lady of Africa, located in Abidjan and dedicated to Our Lady of All Graces.

Other places of Marian pilgrimage are the Shrine of Our Lady of Liberation, in Issia, in the Diocese of Daloa, and the Shrine of Ferké, in the Diocese of Katiola.

The first missionaries, who arrived in Angola in 1491, built a church dedicated to ‘Our Lady Saint Mary’. Today, there are more than one hundred churches and chapels dedicated to the Mother of God in Angola. The Shrine of Our Lady of Muxima is located 130 kilometres from Luanda, Angolan capital, and it is considered by many to be the most popular place of pilgrimage and worship in Angola.

The festival in honour of Our Lady of Muxima – which in the Kimbundu language means ‘heart’ – has been celebrated since 1833. Due to its importance and historical significance, the church, built at the end of the 16th century, was declared a national monument in 1924.

Benin. The Grotto of Our Lady of Arigbo in Dassa-Zoume,

In Benin, the Grotto of Our Lady of Arigbo in Dassa-Zoume, was blessed in 1954, and it has gradually become an international pilgrimage centre. Every year on 15 August this place is the pilgrimage destination of people arriving from Benin, Togo, Niger, and Burkina Faso. The shrine of the Divine Mercy of Aliada is also another popular pilgrimage centre where faithful gather to ask the Mother of God for protection and mercy.

In Linzolo, a few kilometres from Brazaville, capital of the Republic of Congo, one of the first missions founded by the Spiritan Missionaries in 1883, there is a gigantic grotto dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes at the bottom of a magnificent valley. Every year, since the Marian Year of 1987, flocks of faithful have reached this site, which is the most important Marian meeting place in the country.

In 1952, during a Marian congress that took place in Durban in South Africa to celebrate the centenary of the arrival of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate in South Africa, Archbishop Martin H. Lucas proclaimed, ‘Mary Queen Assumed into Heaven’ Patroness of the South African Church.

Our Lady of Ngomé is one of the best-known Marian shrines in South Africa. It is located in the diocese of Eshowe, in the heart of the Zulu region, where it is said that the Virgin manifested herself to a Benedictine nun named Reinolda, who died in 1981. Mary is venerated in this place with the title of ‘Mary, Tabernacle of the Most High’. In Uganda, in the diocese of Arua, in Lagonda, in the north of the country, is the sanctuary of Mary Mediatrix of all Graces, where the Virgin is also called ‘Our Lady Sultana of Africa’.

Ismael Piñón