Social-economic inequality.

According to the estimates of the last census, carried out in 2022, the Dominican Republic has a population of 10,695,000. Of these 3/4, equal to 73% are mestizos, 16% white and 11% black.

The other minor ethnic groups present in the country are Asians, especially Chinese, and Europeans (mainly Spanish). There is also a small presence of Jewish migrants, made up of about 600 people, which originated between 1940 and 1945 thanks to the visas granted by the Dominican government to allow them to escape Nazi persecution

during the Second World War.

The Dominican Republic is also home to small but vibrant communities of Lebanese, Syrians, and Palestinians who arrived during the Ottoman Empire period of the early 20th century. All of these groups have made great contributions to the growth and culture of the Dominican Republic, and this is reflected in the food, customs, and celebrations of the various regions of the country.

Santo Domingo City. CC BY 4.0/ Ronny Medina. About one million people live in the capital.

Spanish is the official language with variations spoken in different parts of the country and the Spanish dialect that is commonly used is Dominican Spanish, a subset of Caribbean Spanish based on the Canarian and Andalusian dialects of southern Spain. This language borrows some words from the Arawak language and from the African languages spoken by the populations who arrived on the island, including some words from archaic Spanish.

From an administrative point of view, the country is divided into 31 provinces which must be added the district of the capital Santo Domingo which constitutes the major economic and cultural centre, as well as the oldest European city in the ‘new world’, since the year of its foundation dates back to 1496. About one million inhabitants live there, while the entire metropolitan area, called Gran Santo Domingo, has a much higher population of about 2.6 million. In addition to Santo Domingo, the main cities include Santiago de los Caballeros with about one million inhabitants, Los Alcarrizos which has 245,000, and La Romana 225,000. The rest of the population live in smaller urban centres, while around 30% of the population live in rural areas.

The Basilica-Cathedral of Our Lady of Altagracia in Salvaleón de Higüey. Around 70% of the population belongs to the Catholic church. Photo: Ph

From a religious point of view, about 70% of the inhabitants belong to the Catholic faith, 20% adhere to the Protestant faith, and the remainder follow Islam, Judaism, Caribbean Vodou, Eastern religions or other beliefs, or declare themselves non-religious. It must be said that the Catholic Church, over the centuries, has contributed decisively to the socio-economic development of the Dominican Republic through the implementation of numerous development projects and the creation

of schools and hospitals.

The living conditions that the population has to deal with are not at all satisfactory. Despite the economic growth of the last decade, it is estimated that a large portion of the population still live below the poverty line. This is clearly seen in aspects such as the quality of health and the lack of basic means for a large part of the population such as drinking water or electricity. In recent years, this economic and social disparity has generated numerous internal tensions also favoured by the spread of corruption, a social scourge that affects the judicial system and the proper exercise of police activity.

The spread of child prostitution is another direct consequence of the endemic state of poverty of the Dominican population. The phenomenon, which was also accentuated following the economic and financial crisis of 2008, was denounced by the major international organizations also due to the high number of cases which often give incentives to families in a state of poverty. In fact, as the economic crises worsen, there is an increase in the phenomenon which, in addition to minors, involves the adult population, both female and male. The latter is based mostly in tourist resorts such as Boca Chica, Puerto Plata, and Santo Domingo. There is also the international traffic of Dominican women, destined to be exploited above all in Western Europe,

Argentina, Brazil, and Costa Rica.

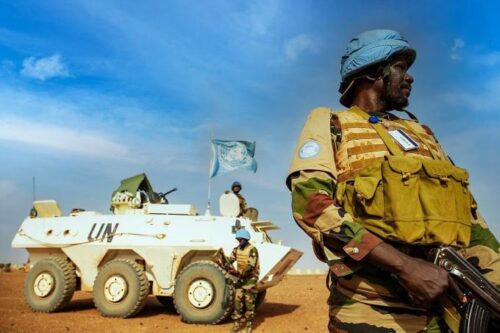

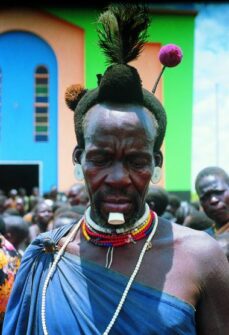

Illegal Haitian working in the sugar plantation. CC BY 2.0/Fran Afonso

In the last decade, within the political-administrative apparatus, there has also been an increase in individual and group interests, corruptive networks with a significant presence of actual criminal components, which have deeply penetrated and weakened the political system causing a significant reduction of trust in democracy and political parties. These, with few exceptions, end up occupying a grey area that makes the differences between them irrelevant and mobile. At the same time, favouritism has become widespread even among social actors.

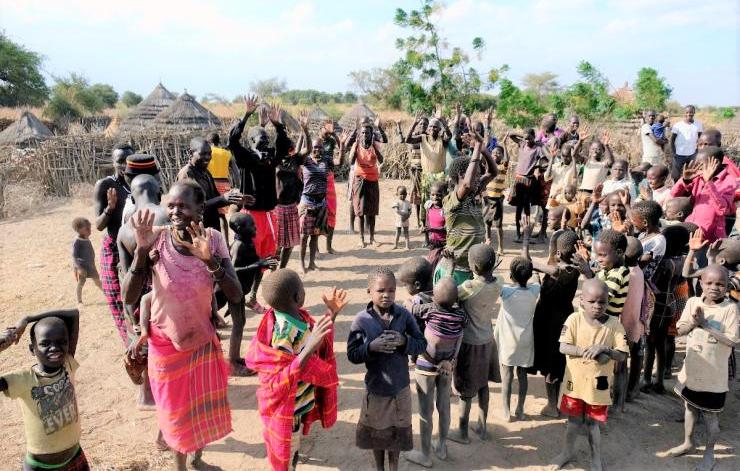

These problems are also to be associated with those of Haitian migrants gathered in villages called bateyes, lodgings built among the plantations with recycled materials without sanitary facilities or running water. Many of them, once the harvest period is over, find themselves in the position of not being able to leave the country because they are in debt and illegally present. Their children were born in Dominican territory, but the lack of documents prevents their recognition either by the Dominicans or the Haitians, with the result that basic rights such as access to school and medical care are denied. This limbo, which offers these subjects no alternative, means they must work on the plantations in conditions of slavery, thus fuelling the vicious circle. (Open Photo: ©aleksrybalko/123RF.COM) – F.R.