Burkina Faso. Masks: the spirits of the forefathers.

Masks are a link between the earthly and the spiritual; they maintain the culture and values of a community. They are sacred objects that appear during funerals, weddings and ceremonies to inaugurate the harvest or to ask for more rain. The urban exodus of many young people is compromising the culture of masks.

Masks are not just beautifully carved pieces of wood. They are not even a sculpture or a decorative object hanging on a wall. “If you are born into a culture where masks have power, you will never be able to get out of it, even if religions, both Islam and Christianity, have shaken everything up,” explains Ahmed Traoré, a wood craftsman from the Artisan Village in Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso.

This carpenter, who can craft both wooden plates and Bwaba masks – typical of the Bobo ethnic group, the majority in the western part of the country – has been carving masks used in ceremonies and rituals throughout the country for over 20 years.

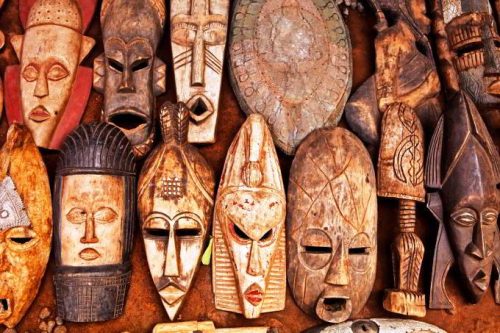

West African Art Masks. They are sacred objects that appear during funerals, weddings and ceremonies. Shutterstock/Linda Hughes

In Burkina Faso, there are 65 ethnic groups, each with its own language and culture. However, most of them share the animist tradition, which venerates ancestors and embodies the souls of nature, both human and animal and plant, in objects.

Masks are sacred objects that appear during funerals, weddings and ceremonies to inaugurate the harvest or to ask for more rain, but you never know who is behind them. There are also family and even personal masks, which can be kept at home to be venerated when necessary. In addition, there are the so-called ‘passport’ masks, which are much smaller and pocket-sized, ideal for taking on trips. “A mask in itself has no power, but once it is brought to the village, a ceremony is held, people’s hair is tied to it, it is washed with potions, and even sacrifices are made so that it can then be venerated,” Ahmed explains.

First steps

Masks are a system and a link between the earthly and the spiritual, as well as maintaining the culture and values of a society. For example, only those who have passed the initiation rite can wear masks and dance with them. Milogo, 30 years old, is a young man of the Bobo ethnic group. Every year, at the beginning of March, the village chief gathers all the men of the community to inform them of who has been chosen

for the initiation rite.

The African masks have a social and religious function. Pixabay

This initiation rite marks a before and after in the lives of young people in all communities because it allows them to pass into adulthood, which also means that they are the bearers of tradition and, therefore, guarantors of the continuity of mask ceremonies. It is in these initiatory steps that young people learn the dances, the meaning and the secret language of the masks.

During this month, the chosen ones live together in the forest to learn the deep meaning of this tradition, which is preserved through oral culture. Afterwards, the village chief – a person with almost divine powers, often older and respected by the community members – will decide the day when the masks will come out of the forest to participate in the ceremony. “This is the moment when the masks return from the camp to dance.The ceremony lasts three days,” says Milogo. But not everyone can participate in this sacred celebration.

In the Bobo ethnic group and in Milogo’s village, only very old women and the Pulot, women of the Peul ethnic group (a nomadic community present throughout the Sahel) can participate.

West Africa. A man in the traditional Zaouli mask dancing. Young people learn the dances, the meaning and the secret language of the masks. Shutterstock/Beata Tabak

This concept, a UNESCO intangible heritage, which could be translated as ‘playful alliance’ is also part of the basis that binds ethnic groups together and keeps them at peace. “The playful alliance is not a personal relationship, but a social structure that dramatises and jokes about past conflicts to facilitate the search for peace,” explains Doti Bruno Sanou who holds a PhD in history. The Bobos and the Peúles, with their agricultural and pastoral traditions, have had conflicts and now laugh and joke with each other. However, they cannot marry each other. For this reason, the only ones excluded from the ceremonies are women of marriageable age. These are the unwritten social mechanisms that are learned in initiation rites and that structure the community in the villages of Burkina Faso. “The masks or statues have a social and religious function that embodies the spirit of the ancestors and totemic animals,” explains Vincent Ouattara, professor of African culture and literature at the Norbert Zongo University in Koudougou.

Masks and stools

“For carving, I use local wood,” Ahmed explains. Fromager wood, shea wood and Nére wood, but not all of them are used to make masks. “Nére wood is only used to make stools,” he explains. This is because masks are not the only objects venerated or the only ways of expressing oneself: the Lobi ethnic group, for example, have wooden stools. For men, it has three legs and a person’s face carved on the backrest.

The Lobi have no hierarchies, and everyone ‘has their own backrest,’ as their stool represents. They are also matriarchal, with sons and daughters adopting their mothers’ names. There are no masks, but older women have a statue of a god at home, which they call batebá.

The importance of distinguishing between masks created for rituals and those that are purely artistic. 123rf

The Bobo, who have a mask, give a man a four-legged stool after marriage. It is traditional for the woman to prepare the first meal she cooks at home on it. Ahmed picks up the stool and holds it close to his belly: “This is how we walk to community meetings. He adapts it to his body with a simple organic movement, without thinking about it.

“Young people have forgotten the rural areas, they live in the city and don’t even know what the masks of their ethnic group are,” Ahmed laments, while acknowledging that everyone needs to return to their villages to reunite with their masks and their venerated objects. “If one day you promised something to the mask, you are obliged to return, if you don’t, you will have more and more bad luck,” he stresses and adds: “There are many believers of other religions who go to the village at the end of the year to return what they owe to their mask,” he explains laughing. In 2024, for fear of losing these traditions, the government of Burkina Faso decreed May 15 as the Day of Customs and Traditions, a day of celebration to perform rituals and valorise culture. However, 72% of the Burkinabe population live in rural areas, where the culture of masks is more alive. According to Professor Ouattara, the problem is not that the tradition is being lost, but that the masks are being ‘commodified’ and are entering the commercial game.

Young people have forgotten about rural areas. They live in cities and don’t even know what masks their ethnic groups wear. 123rf

“There are artists who make copies and then sell them, and in the end, they only serve as decorative objects,” he says. He also stresses the importance of knowing how to distinguish between masks created for rituals and those that are purely artistic. However, Ouattara also highlights the efforts of African states to protect this tradition. “There is the Porto-Novo mask festival in Benin and the Pouni festival in Burkina Faso,” he points out. The latter has been held since 1990, 130 kilometres from the Burkinabe capital. For three days, music accompanies masked dancers from different regions. “It’s magnificent and very precious,” explains Ouattara. Another event is the International Festival of Masks and Art held in Dedougou, the fourth largest city in the country, an event that had to be suspended in 2022 due to insecurity caused by the presence of terrorist groups in the Boucle de Mouhon, but which in 2024 returned to host the music and the tiring dance of the masks. “We are sacrificing and destroying tradition for commercial reasons, not for the modernisation of our society,” concludes Ouattara. (Open Photo: A traditional African mask hanging on a wooden fence. 123rf)

Elia Borras