West Africa. The war between Ukraine and Russia is spilling over into the region.

The war between Russia and Ukraine is having an increasing impact on Africa. A recent proposal by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to supply Ghana with drone technology has caused tensions in West Africa, where Ukrainian military aid to Tuareg rebels prompted three Sahel countries to sever diplomatic ties with Kyiv.

The war between Ukraine and Russia has no geographical limits. In August 2023, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba vowed to ‘liberate Africa from Russia’. A year later, Maria Zakharova, spokeswoman for the Russian Foreign Ministry, accused Kyiv of opening ‘a second front in Africa’.

President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Photo: President.gov.ua

The latest development in Kyiv’s continental offensive came in the form of a statement by President Volodymyr Zelensky on 11 July, following a telephone conversation with Ghana’s President, John Dramani Mahama. In a post on X following the call, the Ukrainian president said that Ghana was interested in producing various types of drones and in Ukraine’s experience gained during the war with Russia. Ghana is therefore ready to finance the production of Ukrainian-made drones to defend its 2,000 km border with Togo, Côte d’Ivoire, and Burkina Faso.

Particularly serious concerns have been raised regarding the border with Burkina Faso, which has experienced an escalation in jihadist attacks since 2020. These attacks have been carried out by groups linked to Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara. Spillover jihadist attacks have also been experienced by neighbouring Togo.

Ukraine undoubtedly has something to offer. Since the Russian invasion in February 2022, the country has developed a wide range of unmanned aerial vehicles, including first-person view drones for reconnaissance and precision strikes, as well as larger, long-range systems. Such technology could enhance Ghana’s border surveillance capabilities by enabling real-time monitoring of remote areas and a rapid response to incursions. Zelensky’s offer comes at a time when Ghana is planning to increase its defence budget by 11% during the 2025–2029 period to address the potential threat of jihadism in the north and piracy

in the Gulf of Guinea.

President of Ghana, John Dramani Mahama. Photo US Dep. of State

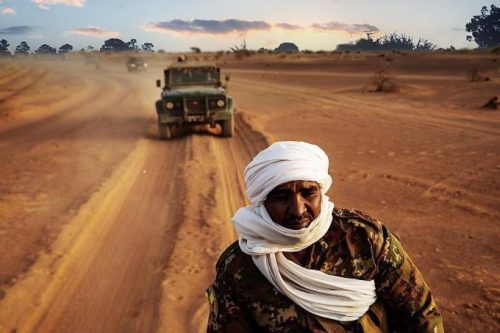

If implemented, the deal between Ukraine and Ghana is likely to upset the leaders of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. All three countries have been at odds with Kyiv since 27 July 2024, when an army convoy composed of Russian Wagner mercenaries and Malian soldiers was attacked near Tinzaouaten, close to the Algerian border in northern Mali, by Tuareg pro-independence rebels from the Permanent Strategic Framework for the Defence of the People of Azawad and jihadists from the Support Group for Islam and Muslims. According to the rebels, over 80 Russian fighters and 47 Malian soldiers were killed in the battle. The three countries’ anger against Kyiv was stirred by a statement from Andriy Yusov, spokesman for the Ukrainian Defence Ministry’s Intelligence Services, who claimed victory for this massacre. During a television interview, he boasted that the Tuaregs had received the necessary information to carry out a successful military operation against Russian war criminals.

FPV . Ukraine Drones.

Sources close to the rebels confirmed that Ukraine had provided intelligence on the movements of the Wagner column, as well as training the Tuaregs to operate explosive-laden drones.Additionally, Ukrainian inscriptions were found on the remains of the drones, and experts alleged that they may have been operated by Ukrainian soldiers. The publication of a social media video celebrating Wagner’s defeat by Yurii Pyvoravov, the Ukrainian ambassador in Dakar, added to Mali’s fury. Bamako and Niger soon broke off diplomatic relations with Ukraine. The Senegalese government expressed its irritation and reminded Kyiv of its diplomats’ duty of discretion and non-interference. It also condemned the ambassador’s “apology for terrorism”. In August 2024, Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger jointly appealed to the UN Security Council, urging it to condemn Ukraine’s “overt support for terrorism”.

A convoy of the Malian Armed Forces (FAMA). UN Photo/Harandane Dicko

In this context, Zelensky’s offer to Ghana seems to be as much about countering the Russian presence in West Africa as it is about fighting jihadists. This is especially apparent when considered alongside another offer made to Mauritania the previous month, amid tensions between Nouakchott and Bamako following the expulsion of Malian migrants in March. On 25 June 2025, Maksym Subkh, the Special Envoy for Ukraine in the Middle East and Africa, told Reuters that Kyiv had proposed sharing technologies and battlefield achievements with Nouakchott, including training programmes for Mauritanian soldiers.

However, this strategy carries risks. For example, Ukraine’s involvement in Sudan backfired for Kyiv, as demonstrated by the angry communiqué issued by the Khartoum government on 7 June 2025. ‘Ukraine’s involvement in supporting other groups in Libya, Somalia and Niger has been established. It supports organisations such as Boko Haram and al-Shabab in Somalia, and in Sudan it provides support to the Rapid Support Forces by supplying them with drones,” a Sudanese Foreign Ministry official complained, as quoted by the Russian propaganda

outlet Russia Today.

A Mauritanian soldier. Kyiv has proposed training programmes for the Mauritanian Army. US Dep. Of Defence.

Some of these allegations are contradicted by the facts. For example, when the Ukrainian ambassador in Abuja presented his letter of credence to President Muhammadu Buhari of Nigeria in 2019, he publicly declared that Kyiv had signed contracts to supply Nigeria with military equipment and munitions, and would continue to support the fight against Boko Haram. In June 2024, the Horn Observer reported that Ukrainian Special Forces were training and advising the Somali Army’s Danab special operations force under the supervision of the US private security firm Bancroft Global Development, citing Somali military sources. This raises doubts about Ukrainian support for al-Shabab militias. Nevertheless, such a presence has the potential to heighten local tensions.

According to the Horn Observer, two Somali officers reported that Ukrainian Special Forces had arrived to counter potential Russian activities in an ambiguous context. During that year, President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud had expressed an interest in a security partnership with Russia, yet he also attended the Ukraine peace conference in Switzerland. The conference concluded with a communiqué that condemned Russia’s aggression.

Displaced people in Darfur. The civil war in Sudan, which has been ongoing for more than two years, has killed tens of thousands of people and displaced over 11 million. File swm

In the case of Sudan, the anger of the Khartoum authorities can be explained by the shifting alliances of both Ukraine and Russia. At the beginning of the conflict in 2023, Ukrainian special forces fought alongside the Sudanese Armed Forces against the rebel Rapid Support Forces, who were supported by the Wagner Group. However, the situation changed in February 2025 when the Russians secured an agreement from the Sudanese Armed Forces to establish a naval

base on the Red Sea.

Ukraine is increasingly finding itself on the opposite side to Russia’s allies across the continent. Kyiv has hosted training programmes for the Libyan government’s land, air and naval forces and has provided assistance with sea and air border security. The main aim was to hinder the operations of the commander of the Benghazi-based Libyan National Army, Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, who is backed by Russia’s Africa Corps. Ukraine has undoubtedly been successful in opening a front in Africa against Russia. But only to a certain extent. It has not managed to reduce the Kremlin’s influence or ‘liberate Africa from Russia’. For Africans, the main outcome is that this rivalry has fuelled further divisions among them, reminiscent of the Cold War era. (Open Photo: Ingall, Niger. Shutterstock/Katja Tsvetkova)

François Misser