The Giraffe. The Queen of the Savannah.

Lessons, strategies, and curiosities. What we know about the giraffe, the tallest animal in the world… with a big heart. It is an icon of Africa, known for its long neck, its unmistakable spotted coat,

and its elegant bearing. But the giraffe is an animal with other exceptional characteristics that never cease to amaze. Too bad

it risks disappearing.

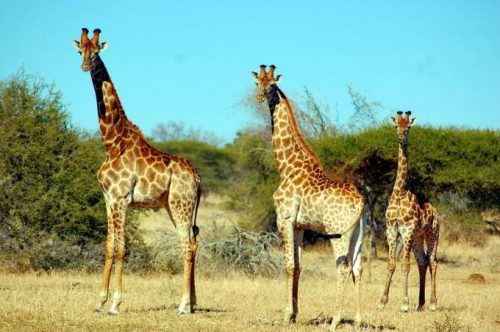

Ndlhulamite: “Tallest of the trees”. This is the name that Zulu and Matabele gave to one of the most iconic animals of the African continent, the giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), with its elegance and majesty, has always fascinated explorers and travellers. Unmistakable for its long neck and spotted coat (the design of which is a unique distinguishing feature between individuals, also, the 8 subspecies present in Africa),

it can reach five and a half metres in height – the tallest

animal in the world.

A perfect body

But such a body – that of the male can weigh more than a ton – is not easy to manage. So, the giraffe had to develop an enormous, exceptional heart, weighing up to 12 kilos, to irrigate the highest parts of its body with blood effectively. Despite its large heart muscle, height and the force of gravity can be a problem. When we stand up suddenly, our head spins a little: we are not two meters high and yet the movement already creates an imbalance in blood pressure.

The tallest animal in the world. Pixabay

Imagine a giraffe, when having finished drinking with its head at ground level, it returns to an upright position: in the space of a second its brain rises by 5 meters… Any other animal would faint instantly, but not the giraffe. In the same way, when it lowers itself to drink, the pumping of the heart, added to the force of gravity, would create such an increase in pressure as to cause cerebral vessels to burst. This does not happen to a giraffe. And think of how many people need to wear tights for varicose veins: the giraffe, despite its height and blood pressure combined with the force of gravity, does not seem to suffer from it at all. Even in this case, its anatomy provides formidable solutions: in the highest part of the neck, just under the skull, there is a complex network of blood vessels that acts as an instant pressure regulator and allows the animal to make rapid and wide movements of the head, up or down, compensating for the change in pressure and preventing the animal from fainting or suffering a stroke. Furthermore, the shape of the skin that wraps around its legs works exactly like supporting tights, compressing the blood vessels, preventing them from dilating excessively due to pressure.

At the table with giraffes

Giraffes are grazing herbivores, that is, they feed on leaves, shoots, and pods, which they select with their long, bluish tongue (which is up to half a meter long) – they have rarely been seen grazing grass. As ruminants, they have four stomachs, in which digestion occurs by fermentation. Their height allows them to access food niches closed to many other herbivores, and for this reason, they can be seen associating with other animals such as zebras and wildebeests, with which they do not develop any sort of competition.

As ruminants, they have four stomachs, in which digestion occurs by fermentation. Pixabay

Giraffes are dependent on water and drink regularly. As ruminants, they cannot lie down, due to the risk of suffocation by gastric fluids. For this reason, they rest crouched in the typical posture that we find in cattle, or standing, often resting their head on the fork of a branch. Another interesting characteristic is the habit of “chewing” bones. It is not uncommon to observe a giraffe picking up a white bone from the ground with its tongue and chewing it like chewing gum: this practice provides it with the mineral salts it lacks in its usual diet.

Societies with no ties

Giraffes emit very few sounds, limited to snorts, sometimes guttural in the male, while the young have a more varied and audible range of calls. The scent glands are also poorly developed and limit olfactory communication. A deficiency compensated by their height and extraordinarily acute eyesight, which allows giraffes to maintain visual contact even at great distances. It seems that a giraffe can spot a predator almost five kilometres away.

A high-ranking male imposes his status simply with his posture and presence. Pixabay

A gregarious animal, the giraffe does not live in stable herds or family groups, but temporarily associates with other individuals and then leaves the group at any time to join another; only the young remain permanently in the vicinity of the mother until weaned. Males only compete during the females’ oestrus, engaging in spectacular fights with their horns, carried out violently by their long, flexible necks. Generally, however, a high-ranking male imposes his status simply with his posture and presence. Young males associate in small bachelor groups and abandon their native territory, migrating to new areas, thus ensuring genetic exchange within the species. As they mature, they tend to become more solitary.

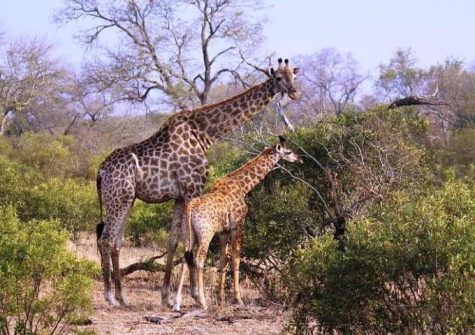

How a giraffe is born

Giraffes do not have a specific reproductive period during the year, although births are more frequent in the rainy season. Males, who reach sexual maturity at around seven years of age, wander from group to group looking for receptive females: courtship takes place through the approach, tasting the female’s urine (to check her receptivity), and a ritual march in which they proceed in pairs.

Giraffes do not have a specific reproductive period during the year, although births are more frequent in the rainy season. Pixabay

After a gestation period of up to 15 months, mothers give birth to a single calf. The newborn can stand on its legs within the first 15 minutes of life. During the first weeks, mother and calf live in isolation to strengthen the bond and allow the calf to learn to recognize the unique pattern of its mother’s coat. The calf is breastfed until 3 or 4 months old, after which it begins to ruminate, becoming independent when it is a year old. While an adult may be considered relatively invulnerable to predators (only a large and experienced pride of lions can take down an adult giraffe), young animals are easy prey.

As a result, they spend a lot of time immobile, both to avoid being spotted and to try to divert energy towards body growth rather than to compensate for useless energy expenditure.

In danger of extinction

Once widespread throughout the semi-arid savannah regions, the giraffe has now disappeared from many of its native territories, resulting in extinction in vast regions of the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. In Africa, this decimation is proceeding at an alarming rate: according to the latest estimates, 117,000 remain (of which 68,000 are adults), a decline of almost 40% compared to thirty-five years ago.

In Africa, the decimation of elephants is proceeding at an alarming rate. Pixabay

Although it is not difficult to encounter them in the main tourist parks, they have completely disappeared in seven African countries, prompting the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to raise the alarm and classify them as a “vulnerable species”. Some subspecies have been declared endangered or critically endangered (for example, there are fewer than two thousand Kordofan giraffes).

What is decimating the population of the world’s tallest mammals is, above all, the deprivation of space and resources: in the last three hundred years, giraffes have lost 90% of their natural habitat due to deforestation, the expansion of agricultural and livestock activities, and to a lesser extent, due to uncontrolled hunting, plus political and social instability in some regions of the continent. (Open Photo: 123rf)

Gianni Bauce/Africa