Sudan. Soft drinks are increasingly tasting blood.

After diamonds and minerals, soft drinks and other products are increasingly profiting from bloodshed. Most of the world’s supply of Gum Arabic, which the food industry relies on, is controlled by Sudanese warlords. Moreover, alternatives are unlikely

to emerge soon.

Traditionally, gum Arabic, derived from the sap of acacia trees, serves as an emulsifier in the food industry, particularly for making soft drinks, including the classic “Coke. ” This product, known in Egypt since the era of the pharaohs as “kami” and used to ensure the cohesion of mummies, is also employed today by breweries to create the desirable foam much appreciated by beer consumers. Additionally, it is utilised in various other industries, including textiles, construction, printing, and painting. In the cosmetics sector, it is used to mix, stabilise, and thicken ingredients in products such as lipsticks.

Most of the world’s production originates from the Sahel region, particularly Sudan, which contributes 70 to 80 per cent of the total. This is where the acacia groves are located in the Blue Nile, Southern Kordofan, and Southern Darfur provinces. Following Sudan are Chad, Nigeria, and other nations such as Senegal, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Eritrea, Egypt, and Southern Sudan.

From Left: General Abdel Fattah Al Burhan’s Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and General Mohamed Dagalo’s paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

However, since the outbreak of the conflict between General Abdel Fattah Al Burhan’s Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and General Mohamed Dagalo’s paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in 2022, there has been growing suspicion that revenues from the production and trade of Gum Arabic are being used to fill the coffers of Sudanese warlords.

Most of the business has been in the hands of the RSF since they took control of the main rubber-harvesting regions in western Sudan

at the end of 2024.

Until then, production had been exported through Port Sudan. The SAF levied export duties, general taxes and forestry fees that amounted to $1,500 per tons of rubber, thus fueling the war effort of General Burhan, who had been sanctioned by the United States for his role in bombing civilian infrastructure, schools, markets and hospitals.

Displaced people in Darfur. Since the outbreak of the conflict in 2022, more than 12 million people have been displaced. File swm.

But now the RSF, accused by the US of genocide in a war that has displaced 12 million people and killed at least 150,000, are reaping most of the rewards. The RSF have also burned fields, raided farms, killed farmers and looted thousands of tonnes from warehouses in the capital, Khartoum. According to the Sudanese Chamber of Commerce, 30,000 tonnes of gum arabic have been looted since the war began. Most of it has been recovered by RSF. This amount represents about a quarter of the world’s annual production of Gum Arabic. According to industry sources, the RSF extorts about $2,500 per truck, which alongside higher transport costs caused a spectacular increase to $4,000 a metric ton from $1,200 before the war. Nowadays, the RSF is controlling almost all the Sudanese Gum Arabic supply chain, which poses ethical challenges for the main traders and clients of the product, who are seriously exposed to the risk of funding indirectly the Sudanese warlords.

Traceability is a challenge.

According to UNCTAD (United Nations Conference for Trade and Development), the main importers are the French companies Nexira and Alland & Robert which buy annually up to 50 percent of the Sudanese Gum Arabic production. Other important clients include the Kerry Group from Ireland, the Dutch corporation FOGA Gum and the Indian Savaji Group which created a joint venture with Alland & Robert in 2019 to sell Gum Arabic on this huge market.

The main importers are the French companies Nexira and Alland & Robert, which buy annually up to 50 percent of the Sudanese Gum Arabic production. Courtesy Nexira.

Further downstream, important Gum Arabic consumers include the powerful American soda drinks giants Coca Cola and Pepsi Cola. Both companies value so much this magic product which stops the sugar from falling to the bottom of the can that they successfully lobbied the US administration to carve Gum Arabic out of the sanctions package imposed on Sudan in 1997 for sponsoring terrorism and providing refuge to Osama bin Laden.

Some of the main consumers such as Nestlé and Mars have made statements claiming they abide by ethical principles. Nestlé says it is committed to source commodities in a responsible way while Mars, which makes M&Ms, claims to engage with its suppliers regarding the situation in Sudan and is prepared to take action in the event of a violation of its policies. By contrast, Coca-Cola and Pepsi have

remained silent so far.

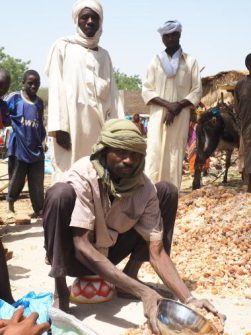

A man sells gum Arabic in a market in Chad. Shutterstock/Pierre Laborde

However, traceability of the product is a challenge. Sudanese gum is smuggled into neighbouring countries that are also producers, making it difficult for Western companies to protect their supply chains from conflict gum. Last March, Reuters reported that traders in Chad, Egypt and South Sudan have begun aggressively offering the commodity at low prices and without proof that it is conflict-free.

Meanwhile, Kenya and Cameroon, which so far had exported small quantities to the EU, have increased their sales on this market after the start of the Sudanese civil war. The Rapid Support Forces are also exporting it via the Central African Republic. Egypt, which traditionally is a minor exporter, has seen its exports rise as well, according to industry sources. According to Reuters, exports from South Sudan have also increased since the beginning of the Sudanese civil war.

Diversification, a long process

The identification of the source of origin is also difficult because traders in the neighbouring countries are reluctant to reveal that they may be involved in smuggling operations or in the resale of stolen products. Industry consultants estimate that nearly all the Sudanese production, now under the RSF’s control, is smuggled, although the Association for International Promotion of Gums (AIPG), the main industry lobby which represents the main processors of the product, declared last January that there was no evidence of links between the gum supply chain and the Sudanese belligerents.

Sudan. Warehouse for storing Gum Arabic. Most of the world’s production originates from the Sahel region, particularly Sudan, which contributes 70 to 80 per cent of the total. Photo: UNOPS

Nevertheless, major players such as Nexira implicitly acknowledge the existence of such a link and seek to protect their reputations by arguing that they have taken steps to reduce the impact of the conflict on their supply chain by cutting imports from Sudan and diversifying their sourcing to ten other countries. But such diversification is a long process: according to Bloomberg, the French company has imported at least 149 shipments totalling 3,679 tonnes of gum arabic from Sudan since the war began. Some of Nexira’s imports came from the Sudanese company Afritec, which has paid extortion money to the RSF.

The main Gum Arabic processors and buyers belong to the Sedex platform used by companies to assess and manage ethical and sustainability risks within their supply chains. But Chadian traders are often not able to provide a Sedex certification that guarantees buyers that their suppliers meet sustainable and ethical standards, while Sudanese suppliers in Sudan say that buying Gum Arabic that meets ethical standards has become nearly impossible.

A few alternative

The problem is that in the short run, there are very few alternatives to replace Sudan, the swing producer of the commodity. Chad or Nigeria are also producers but it would take years before they could boast from groves large enough to compete with the Sudanese ones. According to the chairman of the Chadian Gum Arabic Exporters Association, Abechir Ahmat, the demand is soaring there but also in Mali and Niger.

Pieces and powder of raw gum arabic.CC BY-SA 3.0/Simon A. Eugster

The 10 percent growth of the world market of gum Arabic up to 2 million dollars by 2030 projected by the Market Research Future experts is a powerful incentive for Sudan’s neighbours to build an important alternative production capacity. Chad has a huge potential to become such an alternative, since it could produce the double of the current global crop, says a note from the economic service of the French Embassy in Yaoundé. But for the time being, there is no alternative to the Sudanese production.

More specifically, there is no immediate alternative to natural Gum Arabic. However, should the main consumer countries, the European Union, Japan and the United States, declare a boycott of ‘conflict’ gum from Sudan, one of the medium-term options could be for the chemical and food industries to develop the production of synthetic emulsifiers.

But the consequences of such a well-intentioned policy could be disastrous for African producers, wiping out the tens of millions of smallholders who depend on Gum Arabic, often organised in cooperatives, in Sudan alone. (Open Photo: Gum Arabic, also known as acacia gum. 123rf)

François Misser