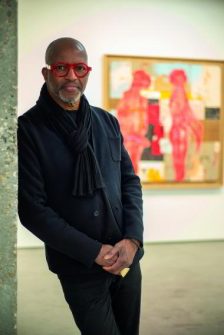

Nú Barreto. Art to Change Society.

He is the most internationally renowned Guinean artist. He has participated in biennials, art fairs, and group and solo exhibitions in various countries in Africa, Europe, America, and Asia. He is committed to showing the world his ideas for transforming Africa.

Manuel Jerónimo Barreto da Costa de Oliveira, known simply as Nú Barreto, was born in 1966 in São Domingos, Guinea-Bissau. He began drawing at an early age, in a family environment where artistic talent was evident. Comics played a fundamental role in his learning process and continue to influence his current work, as can be seen in the influence of these publications, he exchanged with friends.The death of his brother forced him to put his career on hold, but his artistic restlessness drove him to explore the world of photography. Supported by his uncle, he went to France in 1989 to study computer engineering, but his stay in Paris ignited his passion for photography. He attended the École Nationale des Métiers de l’Image and returned sporadically to drawing. In 1992, Nú Barreto exhibited for the first time in France.

“I focus on what hurts, to inform consciences and make amends, if possible.”

He has promoted his work in many countries and focused on art as a means of social commentary. An example of this is one of his most recognisable lines of creation: flags. One such piece is La source (The Source), in the collection of the National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C., in the United States, in which Barreto used several controversial books by African writers to reflect on African wisdom. The artist stated, “During the presentation of the work, I spoke with several people who didn’t know that the University of Timbuktu was founded long before the Sorbonne in Paris.”

He considers himself an artist who pays close attention to people’s behaviour: “When they want to be human, they are; when they don’t want to be, they aren’t,” he says. He takes responsibility: “I focus on what hurts, to inform consciences and make amends, if possible.”

Many styles but a single mission

Nú Barreto cannot define his style. He classifies it as a blend of styles that he tries to incorporate into his creations. One of his inspirations comes from comics published by the American Marvel. Its forms are visible in the morphology of his characters. Another style that sometimes appears in his works is hyperrealism.

Then there is another side with more contemporary traits, with less rigour in morphologies, proportions, dimensions, and formats. In his drawings, the Guinean artist includes “tombolas” in which he encloses people or objects. This symbolism is very important in his work.

“My contribution is my ability to propose a more egalitarian society.”

In this sense, his style is similar to that of the Spanish artists Goya (1746-1828) and Antoni Tàpies (1923-2012), who are complete opposites. Other sources of inspiration also include the Dutch painter, sculptor and designer Willem de Kooning (1904-1997), the British visual artists Francis Bacon (1909-1992) and Lucian Freud (1922-2011), and, in terms of surrealism, the Spanish painter Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) and the Belgian René Magritte (1898-1967). He also draws inspiration from Paula Rego (1935-2022), a Portuguese-born British painter, whose characters have an impressive, highly engaging and dense graphic formation.

The symbolism of colours and materials

The use of the colour red is evident in the work of Guinean artist Nú Barreto. He explains: “It has meaning. We function through our hearts, our thoughts, and our ideologies. In my case, red is what I see. I struggle with what I see and with society; just look at the way I dress. My glasses are red, and I always wear black. Red has different interpretations depending on the geographical location, like all colours.

In Asia and Africa, red has a more mystical interpretation, and I use it as the colour of pain, loss, blood, and mistreatment, but it’s also a colour that attracts attention. Black also has the same function, albeit on a different level: it has an impact, draws attention, and amplifies a fact. I use it for these situations.”

His work addresses themes such as inequality, poverty, and corruption because he believes that art can play a role in denouncing and transforming society. We live by culture. Eating, dressing, and speaking are all forms of culture. I don’t know anyone in the world who doesn’t eat, dress, and speak. We may not understand the codes or thoughts of artists, but they are people who embody a vision that must be understood so that society can be better guided. Art and culture calm and enrich society intellectually, accompanying it. We cannot exclude culture from our actions. “So, I realize that, as far as I am concerned, my contribution is my ability to propose a more egalitarian society,” explains the Guinean artist.

An example of this is the exhibition in which he explored recycling through collage. For him, it was a way of expressing a proposal for citizenship, a way of contributing, “not to clean up society, but to demonstrate that all is not lost, that what we think is no longer valid can change and have a new life.”

“The world has become a mirror of indifference among the imperfect. The imperfect has become indifferent to one another.”

He called this exhibition “Imperfect Indifferent.” In it, the imperfect are people. Moreover, the world has become a mirror of indifference among the imperfect. The imperfect has become indifferent to one another. The rise of indifference in today’s society breeds incivility, thoughtlessness, and inequality among people. However, the old can become part of the new, or be repurposed to become new.

The first Guinea-Bissau Art Biennial

Nú Barreto turned to Guinea-Bissau to examine the legacy of the colonial period. Guineans endured war against the Portuguese coloniser, and once colonisation and the war of independence ended, the country was finally liberated. However, the population lacked the desire and determination to develop art. There were no museums, art schools, galleries, or cultural centres, other than those in the embassies.

He and other Guinean artists realised that this situation could no longer continue. Thus, they organised the Guinea-Bissau Art Biennial, which premiered in 2023 in the capital, Bissau. The public’s reaction was spectacular, and starting in 2025, the Biennial will now cover all fields: art, literature, theatre and music. The 2025 edition, which took place from May 1st to 31st, highlighted Creole, a language that represents a meeting and blending of societies and civilisations. The aim was to reverse the cycle of coups, wars and drugs, demonstrating that the Guinean nation is not like that. (Photos: José Luis Silván Sen)

Gonzalo Vitón