Mauritius. Erosion of democracy.

Mauritius is considered a beacon of good governance, but during the Jugnauth administration, there has been a decline. The last elections saw the victory of the opposition. The challenges facing

the new prime minister.

Mauritius, once considered a bastion of liberal democracy in sub-Saharan Africa, has seen a significant decline in democratic standards over the past decade. According to the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, Mauritius is undergoing “autocratisation.” This trend can be attributed to a dysfunctional mix of ethnicised politics, “dynastic”

rule, crony capitalism, and an outdated electoral system

that perpetuates inequality.

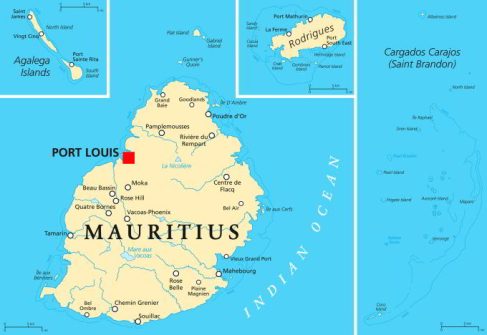

Mauritius Political Map with capital Port Louis, the islands Rodrigues and Agalega and with the archipelago Saint Brandon. 123rf

A particularly critical aspect of this decline is the political instrumentalisation of state institutions, starting with the police force. The judiciary has also been threatened in this process, while parliament, the traditional beacon of democratic debate, has been reduced to a rubber stamp for the executive branch. Over the past five years, civil liberties and digital rights have been scaled back; years that have seen the imposition of heavy sanctions on journalists for content tracked online and the establishment, more generally, of a culture of censorship or self-censorship. Yet in the previous decades, a culture of respect for the will of the people had consolidated.

Since independence, 12 general elections have been held and the power transitions have always been correct as the losing parties have always accepted the outcome of the consultations.

The scandal of “Mr Moustass”

The elections of November 10th brought a historic result: the opposition coalition led by Navin Ramgoolam won all the available seats: 60, against the 0 seats won by the alliance of the outgoing Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth.The vote was dominated by two factors: money and social media. Money refers to the often-obscure dynamics of party financing. Especially during expensive election campaigns. The impact of social media was then sensational.

Prime Minister of Mauritius, Navinchandra Ramgoolam.

One of the turning points of the vote happened entirely online: it was in the ether that the mysterious informant “Mr Moustass” was able to share wiretaps involving important political figures of the islands. Over about 30 days (the duration of the election campaign), 86 videos on this page obtained 13 million views (there were one million registered voters). The videos made public a series of conversations concerning topics such as the cover-up of a murder, political interference in key institutions and general political control of the state. The leaked information reached such a level of diffusion that it pushed the communications regulator (ICTA) to impose a ban on the use of social media. The measure was supposed to last until the day of the election but was actually revoked after about 24 hours due to strong pressure from local civil society. The newly elected government of Prime Minister Ramgoolam now faces arduous challenges: there are measures to be taken to heal the wounds left by this setback to Mauritian democracy just described. Structural reforms are needed, which can re-establish justice, transparency and citizen trust.

The Mauritius flag with a statue of Lady Justice. The judiciary must be freed from political control and return to its neutral role. Shutterstock/Mehaniq

The judiciary must be freed from political control and return to its neutral role, while it will be essential to rebuild the democratic debate in parliament and guarantee a voice to the forces that have now gone over to the opposition. Cases like that of “Mr Moustass” have shown the need for robust data protection legislation and citizen privacy protection. The enthusiasm seen in the streets after the elections should also be read carefully: it is the expression of a deep desire for citizen involvement. Transparency and inclusiveness must be the key words. Just as more “bottom-up” consultation spaces must be guaranteed – from web platforms to town hall meetings – to strengthen a culture of participatory governance. Last but not least, education campaigns on rights and civic responsibilities will also allow citizens to hold their political leaders accountable. (Open Photo: Mauritius flag painted on the wall. 123rf)

Roukaya Kasenally