The Philippines. The church in the sea.

In the Bay of Manila, north of the Philippine capital, it is already possible to see what awaits the inhabitants of the coastal regions of the world: entire areas being swallowed up by the sea.

Perhaps hardest hit is Sitio Pariahan in the province of Bulakan – once a flourishing village but now accessible only by boat.

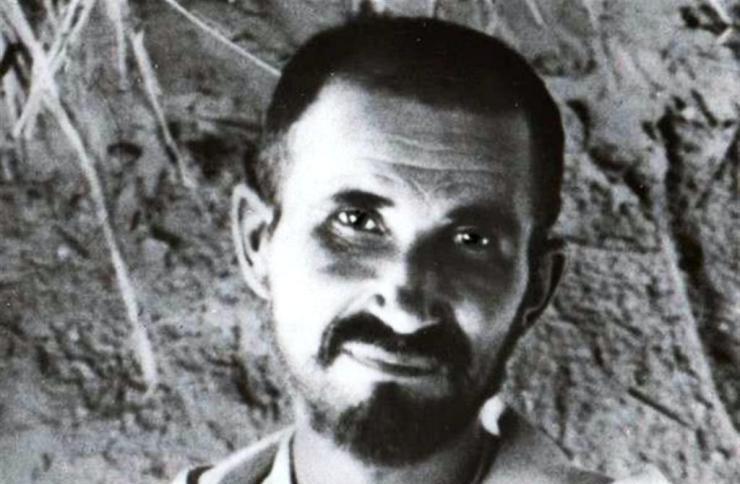

The former inhabitants survive by living in stilt houses. Despite the dangers, especially during the typhoon season, they want to remain at home; earning their living by fishing, the sea is their only means of livelihood. Sitio Pariahan belongs to the parish of Our Lady of Salambao on the island of Binuangan. The parish priest is 45-year-old Fr Rouque Garcia. The community of Sitio Pariahan counts 4,000 members. Another eight villages, called sitios, are located around the Bay: Dapdap, Capol, Bunutan, Kinse-Torres, Sapang, Tucol, Rafael and Calixtro, all of which are accessible only by using the banka, as their small boats are called.

One a month, Fr Garcia takes a banka to Sitio Pariahan to celebrate Mass. The banka initially goes towards the open sea and then turns north into the Meycauayan river, an ancient water-course flanked by dilapidated embankments. Soon, the ruins of houses start to appear. Twenty minutes later, the boat turns left into a tributary. The remains of gnarled tree trunks and individual trees protrude from the water. The guard dogs at some of the abandoned stilt houses start to bark – left behind by their owners to protect the only goods they have. Meanwhile, dark clouds are gathering in the sky above.

The name of the first typhoon of the year begins with the letter A for ‘Ambo’ and it is passing over the Pacific; still at a safe distance. The boatman accelerates and tries to get his bearings. The water is deep at this spot and full of rocks. The river then spreads into a fluvial area covering the remains of a human settlement. Suddenly, in the midst of this apocalyptic scenery, a white building surmounted by a red cross appears on the horizon: the Holy Cross Church of Sitio Pariahan.

The urban landscape of Manila, with slums and skyscrapers. Sea port and residential areas. The capital of the Philippines, view from above.

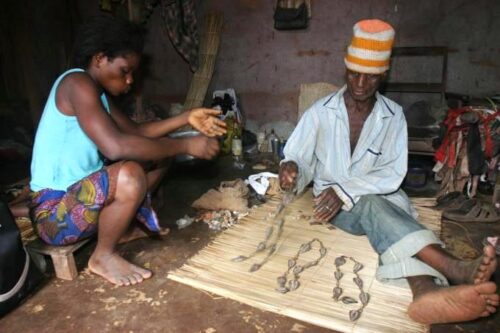

Built in 1984, the church has become the symbol of the fall of the entire region. Surprisingly, the province of Bulakan was a bulwark of the first Christian mission in the Philippines. Spanish Augustinian missionaries came here in 1572, followed by the Franciscans in 1578. Fifty years earlier, on 16 March 1521, Portuguese Ferdinando Magellan, sailing under the Spanish flag, was the first European to set foot on the Southeast Asian archipelago. The Augustinian and Franciscan monks soon succeeded in converting most of the local population to Christianity. The Philippines soon became the most Catholic country in Asia – in honour of the King of Spain. The official celebrations for the quincentenary of Christianity have been postponed until 2022 due to the Coronavirus pandemic.

“It is really something marvellous to celebrate Mass in this church”, Fr Garcia tells us. “But we need to understand that this is not just a church recently devastated by a storm or a flood where the water recedes after a month or two. This is not the case. The church has become part of the sea. Slowly but surely, the water level has risen and is now inside the whole building. Why do I still say Mass in this situation? Because I want to live the Gospel of Jesus Christ and worship in his memory. It is a matter of service, sacrifice, thanksgiving, charity and humility”.

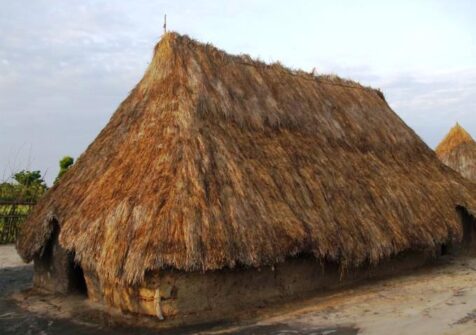

Celebrating Mass is a challenge both for the priests and the people. There are no longer any seats or benches in the church. The priest and the people are in water up to their knees “Sometimes, when the tide is high, the water reaches the windows”, Fr Garcia tells us. It costs a lot for the people of Pariahan to travel to the main church of Obando, so the priest comes to them to say the Mass. All the people live in stilt houses not far from the church.

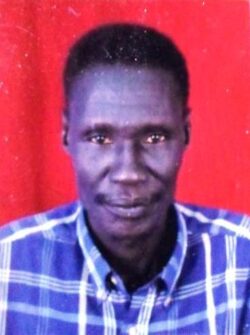

Today, the community of Holy Cross is celebrating its patronal feast. The village head Saturnio Espirito is present and recalls the good old days: “Usually, the brass bands would play as they marched through the streets and dancers would perform for the feast of Holy Cross. In those days, life was very good here and there were lots of trees and plants everywhere. We could walk along the streets. What has happened here is unprecedented and the people cannot believe their eyes. We never thought it could happen to us “.

Sitio Pariahan was, at one time, a coastal village. It is now permanently under water that never completely recedes, not even in the dry season. We had a school, a basketball court, a church and cement-built houses. Today, most of the buildings are in ruins. The homes of those families who have decided not to leave are now on bamboo stilts. The people live by fishing. The cause of all this? Locals say the flooding started after 2011’s Typhoon Nesat, which devastated the area and destroyed dikes that kept water out, but according to experts, the problem lies beneath the surface. It’s called land subsidence, or the sinking of land due to the over extraction of groundwater through deep wells. Most provinces outside Metro Manila rely on these wells for fresh water. Even water providers in rural towns like Bulakan take water from below ground before distributing it to homes through pipes. According to Mahar Lagmay, professor and executive director of the University of the Philippines Resilience Institute, that land naturally subsides when underground sediments compact but it is usually replaced by new material in time. But in Pariahan, the sinking is just too fast.

According to Lagmay’s satellite monitoring, the village and nearby areas are subsiding by up to 4 to 5 cm a year, which results in flooding. This aggravates the effects of global warming, which raises sea levels in the area by about 3 to 5 mm a year.

Of the 100 houses once to be found in Sitio Pariahan, only 40 are still standing. Most of the inhabitants moved to terra firma in the nearby cities of Taliptip, Obando and Malabon, but they, too, are flooded during the heavy rain season. Similarly, millions of residents in the northern parts of Manila are threatened by flooding and there are evacuation centres in many places. As if this were not enough, the inhabitants are now threatened by a further disaster: right where their village is located, the new international Bulakan Manila airport is to be built. It is expected to cover 2,500 hectares of the sea and to be four times larger than the present airport. In future, 100 million passengers per year will land and take off from this airport.

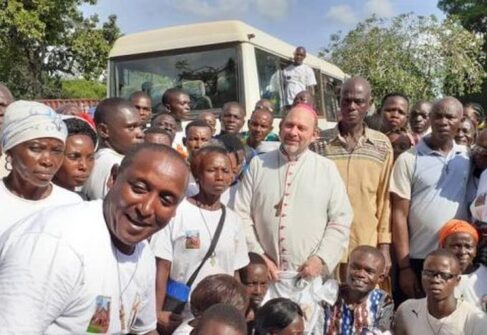

Residents of Taliptip stage a protest action in front of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, to oppose the San Miguel Corporation’s airport project that would displace hundreds of fisherfolk. (Photo courtesy of Save Taliptip).

Last October, the Philippine Senate granted permission for the large-scale project. Large protests were made both by the people of the place and various environmentalist associations. All to no avail. It is only a matter of time until the inhabitants of the village will have to leave their homes for good. At the nearby community of Bunutan, the church bells have been sent to higher ground. The island of Binuangan and the region around Taliptip will feel the enormous impact of the huge airport. Besides the noise and environmental pollution, the reclamation for the mega-airport will further aggravate the flood situation in the Bay of Manila – and all of this is happening while the polar ice is melting at an ever-increasing rate, causing a rise in sea levels. “If it had not been for the Corona pandemic restrictions and the quarantine measures in this parish, people might well have already moved to make way for the airport”, Fr Garcia informs us. “This is why we celebrate every Mass in Pariahan as if it were to be the last”.

Hartmut Schwarzbach/Kontinente