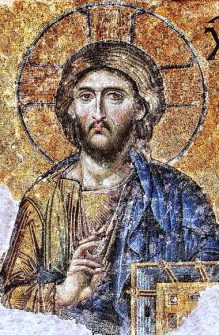

The Catholic Church. A Human and Social Gospel.

There is a Catholic minority in Mauritius, but it is highly valued by both the government and the population for its traditional contribution to social work, in collaboration with the other numerous religious groups present in the country.

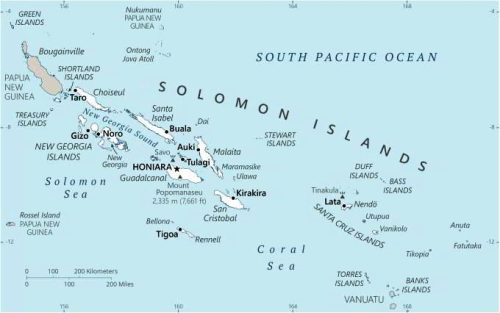

Mauritius today has over 1 million,300 thousand inhabitants, mostly Hindus, Buddhists and Confucians (50%); over 32% are Christians of which 25% are Catholics (and 7% Protestants – Anglicans, Presbyterians, Adventists, Baptists and other Pentecostal groups) and Muslims or of other religious faiths. There are over 330,000 Catholics, in 44 parishes in the diocese of Port-Louis and the apostolic vicariate of Rodrigues erected in 2002.In 1985, the Catholic Episcopal Conference of the Indian Ocean was established by the Holy See, which includes the five bishops of the Episcopal Conference of the Indian Ocean (CEDOI): the dioceses of Port Saint Louis and the Apostolic Vicariate of Rodrigues (Mauritius), Saint-Denis-de-La Réunion, Port-Victoria (Seychelles) and the Apostolic Vicariate of the Comoros.

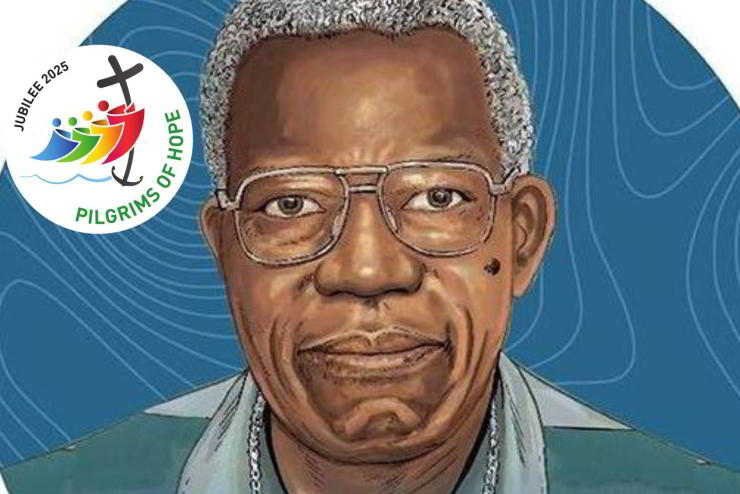

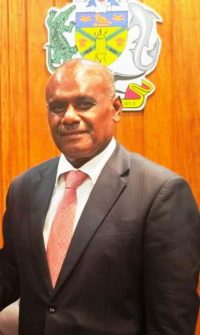

Mons. Jean Michaël Durhône, bishop of Port Louis Diocese

In 1989 and 2019, Mauritius welcomed John Paul II and Pope Francis respectively. The Catholic Church has been present on the islands since the 18th century. In fact, the erection of the apostolic prefecture of the Indian Ocean Islands (now the diocese of Saint-Denis-de-La Réunion) dates back to 1712, which included, in addition to the islands of Réunion, the Seychelles and Mauritius, French colonies, to which Madagascar was added in the second half of the 18th century. The apostolic prefecture was entrusted by the Holy See to the Lazarists, who landed on the archipelago in 1722. Over time, various other missionary congregations, including the Benedictines, Spiritans and Jesuits, joined the Lazarists. The most profound imprint on the development of the Church was left by the Lazarist Jacques Désiré Laval, beatified by John Paul II in 1979 and remembered as the “saint of the island”. He worked there for over 20 years, between 1841 and 1864, dedicating himself above all to the evangelization of the slaves brought from the continent. Those who converted in large numbers formed the first large nucleus of the Mauritian Catholic community, and over the years, in the encounter between black Africans and white European colonizers, they formed the mixed-race majority of Creoles. After independence, in 1968, the government proclaimed religious freedom, and since then, many new Churches, religious groups or syncretistic sects have been created. The notable contribution of the Catholic Church in the fields of education, health and social promotion have always been recognized and appreciated by the various governments that have succeeded one another.

Celebration of Palm Sunday in a parish in Port Louis. File archive.

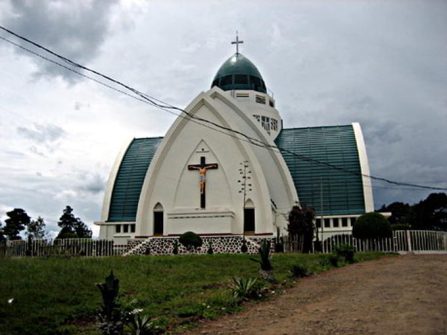

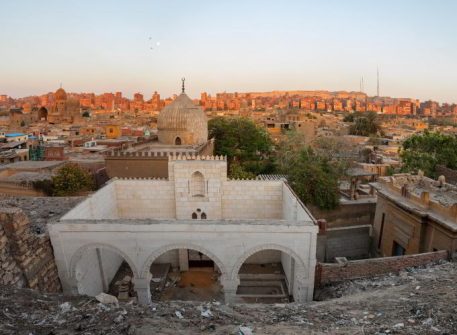

The visit of Pope Francis – as witnessed by many Catholic faithful – helped to consolidate relations between the different faith communities, between which tensions had arisen at the time of independence. “At that time” – says an elderly person present at the time – “the Catholic Church worked very effectively for reconciliation between the various faiths. And today it continues its commitment as an instrument of unity and collaboration”. Even in Mauritius, however, ecclesial activity has been weakening due to the crisis of priestly and religious vocations in recent years. It should also be emphasized that many Catholics and Christians of other denominations are conditioned by the animist faith. The belief of many in the power of magic or the evil eye influences how faith is practiced, often accompanied by the fear of evil spirits and various superstitions. It should be reiterated, however, that the adherents of the various religions, originally from Africa, Europe and Asia and present in all the islands of the Indian Ocean, have mostly cultivated relationships of mutual respect, peaceful coexistence, dialogue and participation in festivities and humanitarian initiatives organized by the adherents of the different religious faiths. (Open Photo: St Louis Cathedral, Port Louis. Shutterstock/Lobachad)

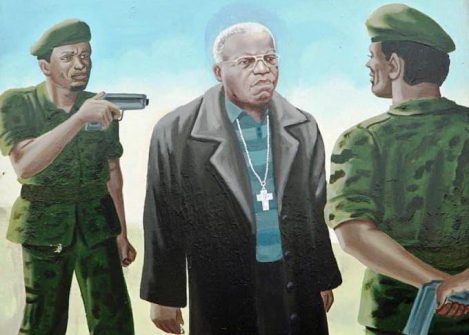

John White