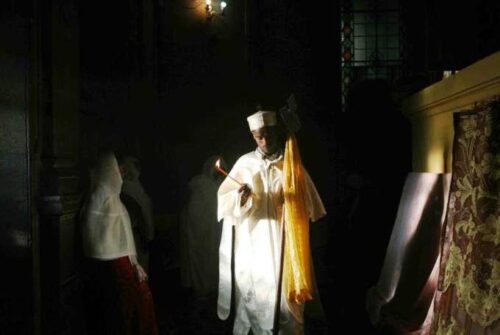

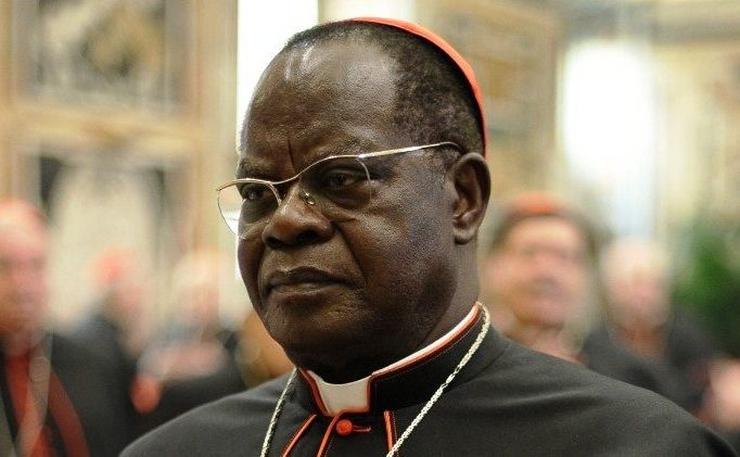

Uganda. A bride Mukiga girl.

The Bakiga or Kiga people are known as people of the mountain. They are a Bantu ethnic group of South Western Uganda and Northern Rwanda. We look at different stages of traditional marriage.

Marriage among the Bakiga has generally been monogamous and it begins with courtship of the couple. The young man identifies the woman he likes and approaches her father. Unlike the usual courtship, among the Bakiga, they will do the Oshwera Abuza (investigation) regarding the family of the young lady. The lady’s family also does the same with the young man. Though in the past, courtship was out of question since the suitor kidnapped the girls.

The investigation also helped families find out if any of them had any serious sicknesses including mental illness, if any of the families were involved in witchcraft practices and rituals, and the virginity of the girl was also investigated. Virginity was rewarded with a goat which was given to her paternal aunt. After investigations, preparation of marriage begins with the paying of the bride price (Okuhingira).

Bride Price among the Bakiga included cows, goats, locally brewed beer. The girl’s father goes to the boy’s family where he is allowed in the kraal to choose the cows, he wanted for his daughter’s bride price.

In the past, many Bakiga owned cows so all bride prices revolved around animals. Today, many things have changed; few people own cows so the number of cows asked for the bride price has reduced.

Marriage was, and is not, a one-person affair among the Bakiga; it is an affair of the extended family which includes the father of the groom and his extended family. The marriage ceremony is a ritual among the Bakiga in which they have stages to follow before the marriage is completed. In the past the introduction ceremony was when the groom was introduced to the girl, because the girl would never know her groom until after he had paid her bride price.

Today, the bride is expected to introduce her fiancé to her parents, uncles, aunts, and grandparents since she is the one who knows him. After which the Kuhingira (Giveaway) follows.

At the Kuhingira, the bride’s father hands his daughter to the father of the groom and tells him to take good care of her. In case of misunderstanding in the couple, the groom’s father is supposed to help them find peace. The girl is also advised not to return home.

Then the Okwaruura (introduction of the bride to the family and to house chores) takes place at this ceremony where the new bride was given a hoe by her family and advised to go and start to work for her unborn children. Today Okwaruura is done but the brides are not given hoes anymore because many of them are corporate women or living in urban areas. Before Okwaruura, the bride was on honeymoon and she was not allowed to do any house chores; she would also receive gifts during this time. The last ceremony before she gets her first born is when her family, her sisters and brothers would pack sorghum, local brew, chicken, and any other gifts, then go to pay their sister a visit. They would carry with them a drum and sing along their way.

When they reach their sister’s home there would be merrymaking: dancing, drinking local brew and lots of food and when returning home their in-laws would also pack gifts in the same baskets which they would carry back to their parents.

Kidnapped by secret admirers

In the past, marriage had another twist amongst the Bakiga. According to old stories some girls were kidnapped by secret admirers and tied to ekyigagara (a stretcher-like mat) and then taken to the home of the suitor and the bride price would be paid later. The Bakiga believed that everyone had a right to marriage even the men considered ugly, and the disabled, whom many girls rejected.

Bakiga girls did not have a say in who they would get married to because marriage was a discussion between men, which included the secret admirer, secret admirer’s father, and the bride’s father.

The kidnapper was considered an ugly or disabled man and was sure no woman would marry him. His friends and brothers would organize to kidnap the girl. The old stories continue that the secret admirer would approach his father and tell him about his intentions for a particular girl and after all investigations, his father would approach the girl’s father and tell him about his son’s intention.

There, discussions would begin but the girl would never know what was happening except that she would be told to reduce on heavy chores, and preparations to beautify her would begin. That was the time the girl would know that something was not right.

The culture dictated that girls never knew the men they were getting married to until the day they came to pay her bride’s price. Since some men did not have the patience, once he admired a girl, many brothers were advised to be their sister’s keepers to protect them from kidnapper husbands. Sometimes the secret admirer would attack the girl’s brother and a fight would ensure that the winner takes the girl.

When going to pay the bride price, the groom and his entourage would walk long distances since it was rare to find a man marrying within the same village. They would get their walking sticks, cows, goats and local brew and walk until they reached a point agreed upon by both sides, there they would sit and rest.

There, they would find young girls from the bride’s home waiting for them with entacweka (small calabashes) filled with enturire and bushera, locally made soft drinks, which were offered to them to quench their thirst and then they would complete their journey.

When arriving at the home they are welcomed with ululations and drumming and singing. The visitors are then given seats and given food to eat before the marriage negotiations can begin. After the meal they begin negotiations, and after the negotiations, the following day the groom is expected to come back and take his bride.

Today the entacweka is taken from the girl’s home after the groom’s entourage arrives. A Mukiga girl had no right to reject a suitor because it could earn her punishments. The girl’s father and suitor’s family discuss the price which he would be given, without him consulting anyone. So, rejecting a suitor meant the bride’s father returns the items he received. She was also not expected to leave her marital home however hard the situation was. In the event she left and asked for divorce, her family was required to return every item given to them for her bride price.

Irene Lamunu