The Ankole cultural spots.

Places, legends, instruments, dances, to preserve the Ankole’s rich and diverse culture. At a glance some of these sites.

Nkokojeru tombs: these are the resting places of the Ankole’s last two kings: Mugabe Edward Solomon Kahaya II buried in 1944 and Omugabe sir Charles Godfrey Rutahaba Gasyonga II, who ruled from 1944, and who died in 1982. There are also other tombstones in this area marking the graves of other royal family members.

Igongo cultural centre: this is for the preservation of Ankole’s rich and diverse culture, and is located where Mugabe’s palace once stood.

Itaaba Kyabanyoro: this is Ankole’s most significant cultural site for it is where the last king of the Bachwezi crafted the sacred Ankole royal drum called the Bagyendanwa. Itaaba Kyabanyoro is the birthplace of the founder of the Ankole kingdom. This drum was a sign of power and legitimacy owned by a Mugabe on the royal seat. This is in Kitagata Hot spring, whose hot springs are believed by many to have healing powers. One of the springs known as the Ekitangata ky’omugabe: it is very significant for it is believed to be the only spring which was used by the omugabe of Ankole. There is another spring known as Mulango named after the Mulango referral hospital, Uganda’s largest referral hospital.

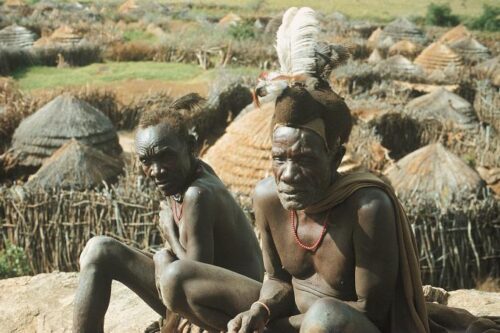

Sanga cultural village: this cultural centre is known as the great Ankole culture and customs centre.

It lies around lake Mburo National Park and is inhabited by the Hima community of Bahima people, the Ankole cattle pastoralists.

Karegyeya Stone is an historical monument found in Kategyega Village in Ntugamo District. Photo: CC BY-NC 4.0/ Tonny Mpagi

The Karegyeya Rock: known locally as Eibare rya Karegyeya, can be found just over a mile outside of Ntungamo in Karegyeya village. The legend of the rock encompasses local traditions of the ancient Bachwezi; semi-gods who took on human appearance but did not die and simply disappeared into the underworld. They were said to be the original, traditional rulers of the empire of Kitara, a probably mythical kingdom that existed in the 14th and 15th centuries and covered parts of modern-day Uganda (including Ntungamo), Tanzania, DRC, Kenya, Rwanda, and Burundi.

The Bachwezi were in turn believed to be related to the Batembuzi, a dynasty founded by Ruhanga, the creator. The last of the Batembuzi rulers, Isaza, is believed in tradition to have married and had a child with Nyamata, the daughter of the king of the underworld, Nyamiyonga. Nyamiyonga was later to seek vengeance on King Isaza for attempting to deceive him over a pact and lured him into the underworld from where he was never to return to the world of men.

The Karegyeya Rock is believed to form an entrance to this underworld and it is believed that the Bachwezi still reside down there, a legend perpetuated by rumors of fires seen at night emanating from the rocks with ashes and worldly goods scattered around them at day break. In order to keep the locals away and to prevent them from exploring the secrets of Karegyeya Rock further, another legend of a giant snake that lurks under the rock also exists.

A snake so large its belly contains a lake, a lake so large that if the rock was ever destroyed the waters from the lake would break free and devastate the surrounding areas like a dam breaking.

Ankole Long-Horned Cattle: (also known as inyambo), these have a dark brown coat and long white horns that curve outwards in the shape of a lyre. They are majestic, elegant animals, able to travel long distances in search of pasture and water.

Their horns are very impressive, almost six times longer than those of European cattle breeds). This breed continues to have a sacred role in the community of Ankole and were once considered the incarnation of divine beauty, a yardstick for women and warriors.

Ekitaguro (Ankole traditional dance): the Ankole people have their most treasured dance participated in by both women and men who dance imitating the movement of their long-horned cattle. Women dance with their arms prolonged above their head forming a symbol of two long horns of their cattle inyambo, while the men jump with vigor holding spears as they stamp the ground imitating the movement of the Ankole long horned cattle. This magnificent dance is accompanied with songs and mimes praising the cattle for providing milk and beef, and making their mooing sound and the sound of the milk pouring into the gourd. (Open Photo: © Can Stock Photo / robin_ph)

Gaaba Lucky Maria