Glasgow COP26. Young people at the forefront of Climate Change.

Not only protest marches. They have contributed with debates and proposals at the COP 26 Climate Change in Glasgow. They have been the real protagonists of the Conference.

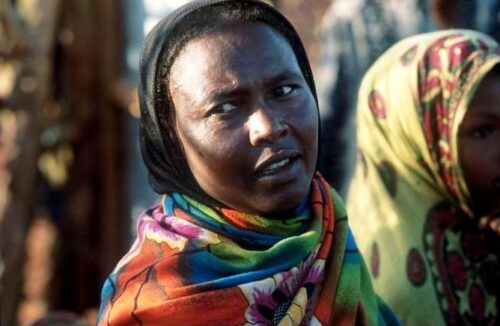

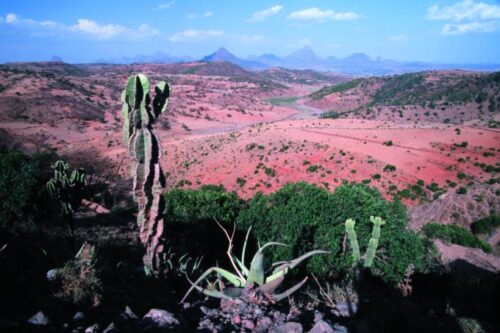

At COP26 in Glasgow, Oumarou Ibrahim from Chad, founder of the Association for Indigenous Women and Peoples of Chad, addressing world leaders on the importance of environmental preservation and listening to Indigenous voices, said: “In the Sahel, my people are the best architects of the Great Green Wall that avoids desertification and restores land degradation. We do this as a duty, not as a job…We use our Indigenous peoples’ traditional knowledge as a tool to protect nature. We don’t stand in front of you as a victim. No. Today, we stand as climate champions.”

While the African continent is responsible for just 3% of global emissions, it remains the most vulnerable region to global warming. The African Union Commission warned that up to 118 million extremely poor people will be exposed to drought, floods, and extreme heat in Africa by 2030. Climate change could further lower GDP in sub-Saharan Africa by up to 3% by 2050.

Elizabeth Wathuti, a 26-year-old from Kenya who founded the Green Generation Initiative, a group that helps young people become environmentally conscious through growing trees, pointed out: “ I have seen with my own eyes three young children crying at the side of a dried-up river after walking 12 miles with their mother to find water.” Wathuti said it’s “painful and heartbreaking” to see people who contributed least to the climate crisis suffer most of the impact. Young people are carrying the burden of fixing the climate crisis, she says. Africa’s youth population is growing rapidly and is expected to reach over 830 million by 2050.

Mary Mathema from Zimbabwe believed that : “African youth should be part of the climate solutions. Instead, we are underrepresented in climate change policy-making and implementation processes at the national, regional and international levels. Integrating African youth in the creation of climate policies, plans, projects and programs

at all levels is imperative.”

Evelyn Acham, a Ugandan activist with the Rise Up movement in Africa, explained why some young people had become “full-time activists” against climate change, giving up education and work due to the urgency of the crisis. She pointed out that the situation was so urgent that they had abandoned other parts of their lives to push for action. She said: “The young people going out there to march give us hope.

“The future belongs to those young people, because they still have a lot of time, they haven’t achieved a lot, but the older generation have already achieved so much and (climate change) probably won’t be so much their problem. “But young people still have work to do, they still have school to do, they have a future to build, so this is our concern.”

Keeping girls in school and taking young climate leaders seriously are keys to tackling climate change said Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai. Speaking to a virtual panel, Malala, 23, said educating girls and young women, particularly in developing countries, would give them a chance to pursue green jobs and be part of solving the climate crisis in their communities.“Girls’ education, gender equality, and climate change are not separate issues. Girls’ education and gender equality can be used as solutions against climate change,” Malala said.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, some 130 million girls worldwide were already out of school, according to the United Nations cultural agency UNESCO, which said more than 11 million may not return to classes after the pandemic.Climate disasters have also been linked with early marriage, school drop-outs, and teen pregnancies, says UN children’s agency UNICEF.

Malala pointed out that it is important to pay attention to youth climate activists: “Listen to young people who are leading the climate movement. Young people are reminding our leaders that climate education and climate justice should be their priority.”

Txai Surui, a 24-year-old indigenous climate activist from the Brazilian Amazon, said “Today the climate is warming, the animals are disappearing, the rivers are dying, and our plants don’t flower like they did before. The Earth is speaking. She tells us that we have no more time. We need a different path, with bold and global changes. It is not 2030 or 2050, it is now.”

She continues: “We have ideas to postpone the end of the world. It is always necessary to believe that doing so is possible. May our utopia be a future on Earth.”The Pacific Islands are extremely vulnerable to climate change. Salome Alinili Maitangi came looking for promises and funding for her community. A young woman from Samoa and Tuvalu, she has travelled the world to make her voice heard and convey a clear

message to leaders.

“Protect the Pacific… we are the smallest contributor to climate change, but we are at the forefront of climate change,” she said.

Moemoana Schwenke from Samoa believes it is important that young women from different communities have a voice at the table. “If our youth work together, we can become better leaders and if we want to work to ensure that our planet does not suffer losses and losses.”

The final agreement of the Glasgow Climate Pact was received with a mix of disappointment with activists, vulnerable smaller states and non-governmental organisations, in particular, describing it as “weak” and lacking “the urgency and scale required” in the face of the climate crisis.

Many youth activists have taken a bleaker view. Vanessa Nakate, a climate activist from Uganda, said: “Even if leaders stuck to the promises they have made here in Glasgow, it would not prevent the destruction of communities like mine. Right now, at 1.2C of global warming, drought and flooding are killing people in Uganda. Only immediate, drastic emission cuts will give us hope of safety, and world leaders have failed to rise to the moment.”

She said the scale of the climate movement was increasing: “People are joining our movement. 100,000 people from all different backgrounds came to the streets in Glasgow during the COP and the pressure for change is building.”

Climate activist Greta Thunberg comments: “The COP26 is over. Here’s a brief summary: Blah, blah, blah. But the real work continues outside these halls. And we will never give up, never. ( Open photo: Hinduo Oumarou Ibrahim delegate from Chad) (swm)