Africa forecast 2022.

The return to the constitutional order in three countries hit by military coups, the downsizing of the French military presence in the Sahel and the instability in Ethiopia are the main challenges.

In North Africa, prospects for the stabilization of war-torn Libya in 2022 are uncertain. By end 2021, both sides were disagreeing about the date of the elections. The Tobruk-based House of Representatives which backs Marshal Khalifa Haftar, as presidential candidate decided on the 19 October 2021, to postpone the legislative elections to January 2022 instead of Dec. 24, 2021, while the Libyan High State Council (HSC), the equivalent of the Senate, proposed in September 2021, to postpone the election to the end of 2022.

The Tripoli-based Government of National Unity led by the provisional Prime Minister Abdel Hamid Dbeibah wanted to hold the parliament elections together with the presidential election on the 24 December 2021.The UN Special Envoy for Libya, Ján Kubiš, supported this objective to create conditions for the return to political legitimacy. But on the 22 December, Libya’s election commission called for a postponement for a month of the presidential poll to the 24 January 2022 after a parliamentary committee said that it would be “impossible” to hold elections on the 24 December.

The run-up to the poll has been marred by disputes over the eligibility of candidates and security fears. The electoral commission rejected the candidacy of Col Gaddafi’s son, Saif al-Islam. There was no clarity either for a while on whether Haftar would run for the presidency. Both are accused of serious human rights violations. Then, the interim prime minister, Abdul Hamid al Dbeibah, also wanted to run. Eventually, they were cleared to run by judicial authorities. Yet, the main problem is that there isn’t an accepted legal basis for these elections. Even if they take place on the 24 January 2022, the challenge is to shore up support for the idea that the country will be run by one central government. If not, splinter groups may go in different directions and tear again the country apart, fear political analysts. There is no guarantee that the different sides will accept the result of the election. Moreover, analysts say that because of the lack of consensus on the rules of the game, it might take more than a month to resolve these issues. In such conditions, the choice of a new date in January by the parliament looks difficult to be approved. In neighbouring Tunisia, where local elections are due on 29 January 2022, the question is whether the national dialogue launched by President Kais Saied after his decision to suspend the parliament and sack the government in July 2021 will defuse tensions. The suggestion that the Islamist party Ennahda might be excluded casts doubt on whether this dialogue will be inclusive enough.

In West Africa, the main concern is Mali where presidential and parliamentary elections scheduled for 27 February 2022 by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to restore the constitutional order after the military coups of October 2020 and May 2021, are likely to be postponed.

In September 2021, the Malian Prime Minister Choguel Maiga warned that the elections could be delayed several weeks or months. At any rate, the credibility of such ballots is not guaranteed since two-thirds of the territory is under the control of various jihadist groups. Besides, France’s military withdrawal from the Sahel will take a decisive turn in 2022. The move started on 12 October when the French military pulled out of the Kidal military base in Northern Mali. Further steps include the closure of the Timbuktu and Tessalit bases, as part of a plan announced by French President Emmanuel Macron in June to put an end to the French anti-jihadist operation Barkhane, started in 2012. According to the plan, the number of French troops will be reduced from 5,000 to 2,500 by end of 2022. However, French military instructors and special forces equipped with drones and fighter aircraft should remain in the country and concentrate on operations against the jihadists in the area around the three borders of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. France should also maintain a military presence in Chad and Niger. But there is little doubt that the French presence in Mali is coming to an end. Algeria’s decision to ban French military aircraft from its airspace makes it more difficult to support operations in the Sahel. Besides, relations between Paris and Bamako have become very tense after the Malian PM accused France of abandoning his country in a speech to the UN Assembly General in September and for failing to consult Mali before announcing its withdrawal decision.

Other factors are leading to a complete withdrawal from Mali. The French government is extremely irritated by the Malian authorities’ decision to dialogue with the Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) or Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims which is affiliated to Al-Qaida.

Another factor that might accelerate the departure of French troops is the decision by the leader of the Malian junta, Col. Assimi Goita, to recruit mercenaries from the Wagner Russian private military company. Paris considers such an initiative as “incompatible” with the continuation of French military cooperation with Mali. Russia already supplied 100 tonnes of military equipment and two MI 171 combat helicopters at the end of September.

In neighbouring Guinea-Conakry, where the elected President Alpha Condé was overthrown by a military coup on 5 September 2021, there are no guarantees either that ECOWAS’s requirement to organise elections within six months, by February 2022, will be met.

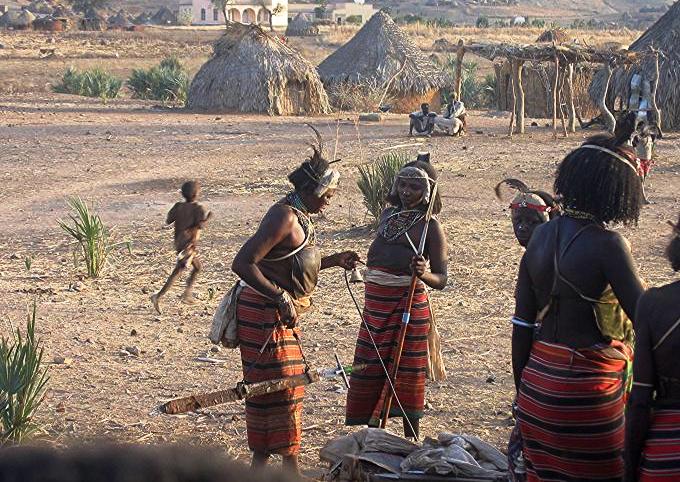

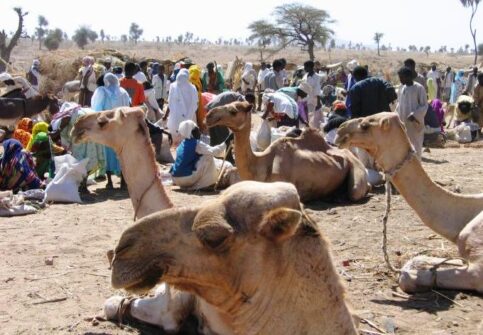

Indeed, the junta led by Col. Mamady Doumbouya, whose members are subject to travel and visa bans imposed by the ECOWAS said it would hand over power to civilians after a transition period but did not set any deadline for its end. By contrast, the national assembly elections in Gambia and Senegal, scheduled for April and July respectively, are expected to be held on schedule. In São Tomé and Príncipe, the Ação Democrática Independente (ADI) of President Carlos Vila Nova who was elected in September with a comfortable majority of 57.6 per cent is the favourite in the National Assembly elections scheduled for the 10 January. In Chad, attention will be focussed on the follow-up of the national dialogue planned to start at the end of 2021 to prepare the national presidential and parliamentary elections, after the interruption of the constitutional order that followed the death of President Idriss Déby Itno in April 2021 in a fight against the Front pour l’alternance et la concorde au Tchad (FACT) rebels led by Mahamat Mahadi Ali.

The problem is whether the dialogue promoted by Idriss Déby’s 37-year-old son, Mahamat Déby, who took the leadership of the ruling Transition Military Council, will be inclusive enough and involve two Libya-based armed groups, the FACT and the Union des forces de la résistance (UFR) led by two cousins of President Déby, Timan and Tom Erdini.

In both Equatorial Guinea and Congo-Brazzaville, there is very little doubt about the outcome of the forthcoming elections in 2022. In Malabo, a victory by Teodoro Obiang Nguema’s Partido Democrático de Guinea Ecuatorial (PDGE) is expected in the House of Representatives, Senate and local elections scheduled for August, owing to the reduced margin of manoeuver left to the opposition coalition CORED. The only question will be the name of the PDGE’s residential candidate for 2023: Teodoro Obiang or his son, Teodorín depending on the health of his father.

In Congo-Brazzaville, observers believe that President Denis Sassou Nguesso’s Parti Congolais du Travail (PCT) will again win the legislative and local elections due in July 2022. But the opposition which, under the umbrella of the Comité d’action pour le renouveau has formed a coalition of 20 parties is taking up the challenge.

Meanwhile, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, people wait with fingers crossed for the political players to reach an agreement on the composition of the National Independent Electoral Commission (CENI). By the end of October, such consensus seemed difficult to reach since 13 opposition parties, including former President Joseph Kabila’s Joint Front for Congo coalition, were calling for demonstrations against the nomination of President Felix Tshisekedi’s appointee, Denis Kazadi who was rejected by the Roman Catholic and Protestant Churches.

In Sudan, the 25 October 2021 military coup dashed hopes that the presidential, legislative and local elections due in 2022 would take place as planned. Indeed, the coup leader Gen Abdel Fattah Burhan who had been chairing the transition Sovereign Council formed by military and civilian leaders, declared soon after that Sudan was still committed to “international accords” and transition to civilian rule but that elections would be postponed to July 2023.

The main concern, after the arrests of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and other civilian members of the transitional government formed after the ousting of former dictator Omar al-Bashir in 2019, was that the coup may lead the country into civil war. Such concern was fuelled by demonstrations in Khartoum and other cities of people calling for a return to full civilian rule.

The concern is even higher in Ethiopia. The question is whether the country may disintegrate with terrible repercussions for the entire Horn of Africa. Diplomats warn that chaos could also be exploited by jihadist groups such as al-Shabab.

In Kenya, where presidential and legislative elections are scheduled for 9 August 2022, everyone fears a repetition of previous electoral years where elections were marred by fraud and violence, with thousands killed and hundreds of thousands displaced. In 2018, the handshake between President Uhuru Kenyatta and his rival, former Prime Minister Raila Odinga helped defuse the tensions which followed the 2017 presidential elections. The question is whether the spirit behind the handshake will hold. Somaliland‘s peaceful parliamentary and local council elections in May 2021 bode well for a similar scenario for the presidential race in November 2022, in a context where the opposition gained a victory over the ruling Kulmiye party which acknowledged defeat and showed remarkable fair play. Yet, President Muse Bihi Abdi, who is expected to seek a second term, may need to govern more inclusively if he wants to prolong his time in office. In Southern Africa, Lesotho expects to hold its general elections in September or October 2022 whereas Angola is preparing to elect its next president in August 2022, amid controversy over election regulations. President João Lourenço is expected to seek re-election but there is mistrust about how the process has been managed and a lack of consensus about recent constitutional amendments concerning the elections.

On September 2, opposition parties called on Lourenço to reject the ratification of the general elections law and return it to the National Assembly. The parliamentary groups of UNITA, CASA-CE, PRS, and Bloco Democrático, called the legislation a “law of electoral fraud and corruption.” The opposition parties also cast doubt on whether the elections will be free and fair. They claim to have been intimidated by authorities. At the same time, they are trying to build a united “Patriotic front” front led by the largest opposition party UNITA with Bloco Democrático and the project Pra-Já Servir Angola against the MPLA which has ruled the country since independence in 1975.

François Misser