Mission. Sharing Our Life.

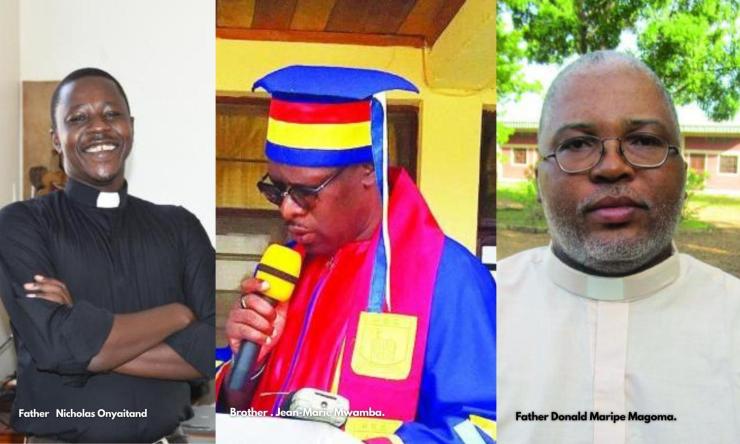

Three African Comboni Missionaries share their vocation journey and their pastoral experience.

My name is Father Nicholas Onyait and I am 33 years old. I was born in Kokorio village, in the Eastern Region of Uganda. I attribute my vocation to my early childhood years. My family was so close to the Church. We used to go to mass every Sunday and we also had daily prayers at home. This ignited the desire in me to become a priest someday because I had much contact with priests.

However, the reality of being a missionary was something that I had never known. This was because in my home parish, there were only diocesan priests and so I thought that all priests were diocesan.

One Sunday, a Comboni missionary visited our school, Teso College. He spoke to us about the missionary vocation and shared his mission experience of working in West Africa in Benin. This was stunning to me. It was not only something adventurous, but it demanded courage.

When I joined St. Peter’s College for ‘A’ level in 2002 this experience kept nourishing me. In fact, the Comboni missionary kept on updating me with the newsletter of the aspirants. In December 2007, I was invited to the first ‘Come and See’ experience in Mbuya where I met many other aspirants. After this, I joined the Comboni Missionaries and I was sent to Alenga parish in Lira in the north Uganda for my pre-postulancy which lasted three months.

This was my very first experience as a missionary and it shaped my missionary attitude and motivation. I got a bit discouraged because the life was very tough; we had to cycle long distances for our apostolate. Therefore, when the senior six results were released, I requested to join the university and come back after my studies. But, of course, I was trying to run away. However, I kept thinking about my vocation and I reapplied after completing my course.

From August 2010 to May 2013, I was admitted for philosophical studies in Jinja. Then from 2013-2015, I did my novitiate in Lusaka, Zambia. I then made my first vows on the 1st of May 2015 in Lusaka. Later, I was assigned to the Scholasticate in Casavatore in Naples, Italy, for four years, 2015-2019. I then returned to Uganda and served in Our Lady of Annunciation Kasaala parish from 2019-2020 in Kasana in Luwero diocese. I concluded my missionary service with perpetual vows in Layibi, Gulu on 15th July 2020. I was ordained a deacon on July 18th, 2020 at the Nativity parish Matany by Bishop Damiano Guzzetti. I then served in Kasaala as a deacon and I was ordained a priest on January 9th, 2021 in my home Parish of St. Pancras Toroma in Soroti diocese.

My most touching experience occurred when I was a novice in the parish of Chama in North-Eastern Zambia. Living among the people taught me the real sense of being a missionary. Thus, it is about sharing the life situation of the people, identifying with the people.

These people taught me the value of humility and motivated me to be able to offer myself in whatever way I could. For me, this was the greatest opportunity I had to witness to the gospel.

The very first hurdle I would say is the culture shock. When you encounter people whose culture and language you do not know, it is a big shock that is also humbling. But I learned to be strong and patient in such moments and also to be open to learning and embracing cultural differences.

There is also that obvious pain of separation from one’s original community and the young generations are often unprepared for it. To the young people of today I would say: “if you are convinced of the call to religious life, God gives you the graces you need for the journey”.

Bro. Jean-Marie Mwamba. Brother philosopher

I was born in 1974, in Kolwezi, the capital city of Lualaba Province, in the south-eastern part of the DR Congo, in a Catholic family of eight children. From my childhood, my mother made me get used to going to morning mass with her. After secondary school exams, I moved to Kinshasa to continue my university studies. In the capital city, I got to know the Comboni missionaries through the friendship I developed with one of them, a native of the Central African Republic, who had come to Kinshasa to finish his theology courses. He is now a priest.

Through reading the life of Comboni and the testimonies of some Combonian missionaries, I was more and more motivated to become a Comboni missionary.

Although my friend was studying to become a priest, the vocation of the religious Brother was still clear to me, but now it became an impellent call and commitment to human advancement.

After some time of discernment, I began my training as a Comboni Brother. And here I must reveal an almost inexplicable ‘conversion’. I had always dreamed of continuing with my technical studies and acquiring a trade or technical profession.

However, during the first years of Postulancy, I came across a science that fascinated me: philosophy. Its beauty bewitched me irreparably. A beauty that increased with the passage of time, mostly spent devouring books and philosophy texts. Today I am happy and proud to be a philosopher.

After my undergraduate studies at the Edith Stein Philosophy School in Kisangani, in 2003, I was admitted to the novitiate at Kimwenza, in Kinshasa, where I spent two years. In 2005, after my first religious vows, I was sent to the International Centre of the Brothers, in Nairobi, to continue my formation.

In agreement with the superiors, I was able to enrol in a graduate programme in philosophy at the Catholic University of the Eastern Africa (CUEA). Having obtained the master’s degree, in 2008, I was assigned to the Comboni Province of Togo-Ghana-Benin, as a member of the formation team of the institute’s Postulancy, at Adidogomé (western suburb of Lomé) and teacher of philosophy in the School of Philosophy.

I have never limited myself to teaching philosophy. I always wanted to carve out time to devote to pastoral ministry. In Adidogomé, I worked with the parish youth group. In 2011 I went back to Kinshasa where I did my perpetual religious profession.

Immediately after, I returned to Nairobi for my doctoral studies in philosophy at CUEA, which I finished by defending my thesis in November 2015. My superior appointed me as a teacher of philosophy at the Edith Stein Philosophy School in Kisangani. The following year, I was appointed Rector of that institution, a position that I hold to this day. And here I am now, a Comboni missionary Brother, engaged mostly in the field of teaching.

Father Donald Maripe Magoma.

I was born in 1979 in Masikwe, in the diocese of Witbank, South Africa. Going to church was my father’s exclusive business. Although he was a pastoral assistant in one of the thousands of ‘apostolic churches’ swarming South Africa, he never bothered to take his children with him on Sundays. Our mother, on the other hand, did not belong to any church, nor did she practice any religion.

The situation changed in 1990, when our parents left us in the care of our maternal aunt Jane, who was a staunch Catholic. For her, taking us to church was the most natural thing in the world. So, at the age of 13, I found myself enrolled in the catechumenate of the neighbouring parish. Two years later, myself and my sister were baptised and confirmed.

So, soon after baptism, I began to attend all the vocational workshops organised by the parish. One day, by pure chance, I came across a magazine published by the Comboni Missionaries in South Africa: Worldwide. The content of the articles and the perspective that I could grasp in the many testimonies reported in it, surprised me deeply; it was no longer a question of finding priests for a diocese, however vast and poor in personnel, but for the whole world, infinitely larger. It was immediately apparent to me that the world’s need for heralds of the gospel was far greater than that of the diocese.

I wrote to the vocation director of the Comboni Missionaries. Within a few months, the decision was taken. In 1997, I entered their postulancy, in Pretoria, as a pre-postulant. Two years later, I started the postulancy proper. In 2001, I entered the novitiate in Lusaka, Zambia. It was the first time I had been outside my home country and I was the only South African among the group of novices.

The two years of novitiate went by without a hitch. In April 2003, I made my first religious profession. Shortly afterwards, I joined the Comboni scholasticate in Kinshasa, DR Congo. Here the difficulties were numerous and nerve-wracking. The language was French, the atmosphere was French, everything tasted and smelt of French… and I could not adapt. I lasted only two years, and then I gave up and decided to return to South Africa, with the intention of abandoning the idea of becoming a missionary altogether.

The provincial superior of the Comboni missionaries offered me to live in the Comboni community of St. Peter Claver Parish in Mamelodi, a township of Pretoria.

There, in a welcoming community and surrounded by my own people, I recovered and regained confidence. Two years later, I returned to Kinshasa with a renewed spirit. I resumed my theological studies, which I completed in 2010. On 7th August of that year, I made my perpetual profession in Glen Cowie Parish, Limpopo Province, South Africa. On 22nd August, I was ordained a deacon, and on 12th February 2011, I was made a priest in my parish at Masikwe.

I only asked for two months’ family leave, and in April I reached my new destination, Chad. Since then, I have worked for a year and a half in a mission in the diocese of Lai, then another year and a half in St. Francis of Assisi Parish, in the diocese of Doba. In September 2014, I was posted to St. Michael’s Parish, in Bodo, also in the diocese of Doba, where I still am.

I am engaged in the fields of first evangelisation, human promotion, training of local leaders, and the common effort towards self-support of the local Church. I like being here. I feel that I am where God wants me. There is no greater joy. The difficulties of the past – and there have been many – appear to me today as small pearls set in the crown of the Church of Africa, of which I feel a humble servant. (SWM)