Next December, the African National Congress will hold its five-yearly elective conference. President Cyril Ramaphosa will be looking for a second term as party leader, in view of the 2024 general elections. Weakened by internal struggles and weak governance, the African National Congress may split in two at the December congress.

For many political parties in the established democracies of Europe, to win 46 per cent of the vote in a country-wide election would be a triumph; but for the African National Congress (ANC), which has governed South Africa since 1994, this result in the local council elections held last November was a disaster.

It is the first time that the party has fallen below 50 per cent of the popular vote, and it continues a downward trend that goes back to 2004 when the party won 70 per cent. In addition, the ANC lost control of a number of big cities, including Pretoria, the capital, and Johannesburg, the financial and economic heartland of the country. In fact, it now controls only three of the country’s eight biggest cities.

Many political observers welcomed these outcomes, since it is not healthy for one party to rule, both at national and municipal level, with an outright majority for such a long time. Predictably, this kind of one-party dominance leads to corruption, non-accountability and a sense of entitlement. Jacob Zuma, whose tenure as President from 2009 to 2018 was characterised by maladministration and crookery, put this in very clear terms when he promised that “the ANC will rule South Africa until Jesus comes back to earth”.

Fortunately, it seems that more and more voters are of a different opinion. Even though they still have a deep loyalty to the party of liberation, the party once led by Nelson Mandela, more and more black voters, especially among the youth, are realising that the ANC has not fulfilled the promises it made 28 years ago, and which it continues to make – to eliminate poverty, to create jobs, to provide a decent standard of living, and to ensure ‘a better life for all’.

It might be expected that this judgment by the voters would provide the ANC with an opportunity to reflect on where it went wrong, and to find ways of improving. It might also be expected that the electoral setbacks experienced by the ANC would be to the benefit of the other political parties, and perhaps even open the possibility of a complete change of government in the next national election, due in 2024.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa.

Regarding the ANC, firstly, the signs are that it will weaken even further, as internal rivalries and competition for positions of power are intensifying. There are broadly two factions within the party. One of them, which supports the party (and national) leader, President Cyril Ramaphosa, is attempting to carry out positive reforms and to help the party to overcome its recent history of involvement in corruption and malfeasance. The other faction, associated with the former president, Jacob Zuma, seeks to prolong the systems of bribery, patronage and nepotism that it benefited from in the years when Mr Zuma was in charge of the country.

The Ramaphosa faction is in the majority in the main decision-making structures of the party, but it is not strong enough – or united enough – to comprehensively defeat the Zuma faction. In addition, the loyalties of a significant number of senior figures are not clear; they tend to take sides with whichever faction seems to be gaining in popularity.

To build unity

Ramaphosa’s approach is to try to build unity above all else. He does not want to see a split in the ANC, and he appears to believe that, by accommodating the Zuma faction rather than acting against it, he can keep the party together. He is also very much aware that, 15 years ago, when the ANC did act against Mr Zuma – who was then Deputy President of the country – it made him into a martyr and he was able to gather enough support to eventually become President in 2009. If Ramaphosa were to move against the Zuma supporters now, a repeat of such a scenario is possible.

All this is happening in the run-up to the ANC’s five-yearly elective conference, which takes place in December this year. Ramaphosa will be looking for a second term as party leader, and while the numbers so far are in his favour, it is likely that the Zuma faction will be strong enough to win a few of the other senior positions in the party. If this happens, we can expect a few more years of internal wrangling and tension, a kind of political stalemate within the governing party.

Cape Town. Parliament of South Africa.

This is bad for the country as a whole. The continued in-fighting in the ANC takes up a lot of the time and energy of government ministers and members of parliament who should be busy running the country and attending to its many needs. While they engage in party political battles, the list of areas in which governance is failing grows longer: state-owned companies that control electricity and water supply are near to collapse; the national airline has almost ceased to operate; various government departments, such as the Post Office, fail to pay their employees’ salaries on time; only a small part of the country’s vast rail network is still functioning; and so on.

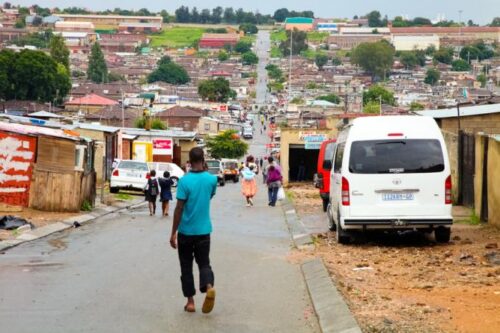

These failures of governance have a serious impact on the economy, and on the unemployment rate which has now reached almost 40 per cent overall, and 70 per cent for young people. This, in turn, means that more and more voters will reject the ANC at the next election – but what will take its place? The second question, therefore, is about the state of the opposition parties.

Ideally, when a governing party starts to weaken after many years in power there will be an opposition party, or more than one, ready to offer themselves as feasible alternatives to the voters. This is not really the case in South Africa. The biggest opposition party, the Democratic Alliance (DA), has also lost support in recent years, down from almost 27 per cent in 2016 to 22 per cent last year, and it has also been affected by internal squabbles and leadership problems.

The only other party of significant size is the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), which has about 10 per cent support. Neither the DA nor the EFF will win anywhere near a majority of the vote in 2024. In addition, these two parties are at opposite ends of the political spectrum, and there is no possibility that they could combine their votes to unseat the ANC. There are numerous other parties too, but they are all quite small and while some might support the DA in a coalition, others are much closer to the ANC.

Which Future?

So, what does all this mean for South Africa’s political future? After so many years of being certain about one thing – that the ANC would maintain its overall majority in the next election – we are now entering into a period of uncertainty. If Cyril Ramaphosa is re-elected as ANC leader this year, he will lead the party into the 2024 national elections; and, since he is personally very popular with the voters, it is possible that the ANC will once again gain 50 per cent of the vote, and form a majority government. On the other hand, the levels of frustration with the ANC’s poor performance are now so high that it might suffer a further decline in 2024. If this happens the ANC will have to govern as a minority or it will have to seek a coalition partnership, either with one of the two big opposition parties or with a few of the smaller ones.

Neither of these options is likely to give us a stable government, at least in the short term.

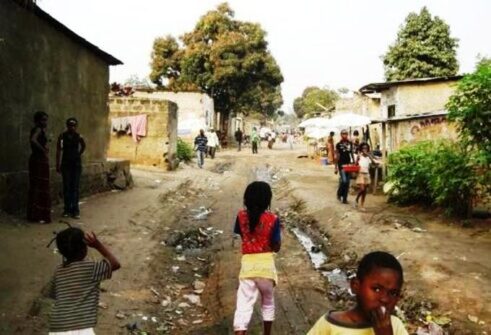

Johannesburg. Gandhi square. ©viewapart/123RF.COM

Another possibility is that the ANC will indeed split. If this happens, the reformist faction will form a new party along social democratic lines, which could find some common ground with the DA, while the ‘Zuma faction’ may well link up with the EFF. Such a realignment in our politics would be very interesting; it could bring a new sense of purpose and rekindle people’s enthusiasm for democratic politics.

However, if the Zuma faction and the EFF were to combine and form a government, the consequences could be severe. Both these groupings are deeply compromised by corruption and both espouse populist policies that would destroy an already weak economy.

But South Africa’s political future is not just about which parties are in decline and which are likely to grow. We have a very active and committed civil society, made up of thousands of organisations committed to human rights, the rule of law, social justice and economic development. These organisations work very effectively to counter governmental abuses and failures, and in this, they rely on a strong and independent judiciary which has proved itself to be a bastion of democratic and constitutional rule.

The big question is whether South Africans will continue to value the multi-party democratic system if, as the years go by, it does not fulfil their needs – decent jobs, good education for their children, adequate living standards, freedom from crime and insecurity, and a healthy environment. With each successive election, fewer people register to vote, and of those who are registered, fewer and fewer actually go to the voting stations to cast a vote.

The task facing all those in leadership, whether in politics, civil society, the churches, the business community or the workers’ organisations, is to spread the message that even if democracy does not guarantee constant progress towards a better life, without it things will only get worse. As long as we remember this, we will be able to find our way through the current uncertainties and emerge as a stronger and more unified nation.

Mike Pothier