Guatemala. Tana’s Sandals.

She never once bought an ice cream. She never had a day off. She has always worked. But she wants to celebrate her birthday. A Guatemalan migrant struggles to live and survive.

She looks at her fingers and hands chapped by 24 years spent cleaning restaurants and shopping malls with chemical cleaners. Originally from Camotán, Chiquimula, Guatemala, Tana left her indigenous clothes, her Maya Ch ‘orti’ gods, and wearing canvas trousers, a t-shirt and tennis shoes, she emigrated along with fifteen other girls from her community. Her home country, now a dry strip of land, has ceased to be the fertile ground that once fed the roots of crops decades ago. Without water and without food, both Tana and hundreds of residents have been forced to emigrate, some to the capital, others to Honduras but the majority determined to take the road to the United States. Some left with the financial help of relatives who were already in the country and others with just a one-way ticket to the capital and with the belief that the Lord of Esquipulas will open the way for them.

That is how Tana decided to emigrate, like most of her fellow villagers with nothing but the clothes on her back. She is the eldest of 11 siblings, her parents are farmers who plough the dry land that has stopped producing. She was sixteen when she left, at dawn, telling them she would go to the capital to find domestic work, but plans had already been made and there were 55 others from Camotán and Jocotán who made their way together, most of them under 18 years of age. Wandering among the hundreds of migrants who were found on the Tapachula side, they managed to reach Naco, Sonora, riding on the top of the Train of Flies, which in southern Mexico is known as La Bestia (the Beast). When they passed through Veracruz, they had some food that Las Patronas throw to the migrants on the train. That was one of the few times they had anything to eat as they travelled with a gallon of water to drink, some oranges and some cold bread they bought in bags in Tapachula.

The 55 who left Camotán and Jocotán crossed the Sonoran Desert without incident and were picked up in Arizona by relatives and coyotes who allegedly transported them to the different states of the country. Tana stayed there in Arizona with the relatives of someone she knew from Jocotán who gave them accommodation and found them work. Since then, Tana has lived in a community, with people moving in and out of their rented house; she has met people of every religion and region of Mexico and Central America. On one occasion, there were two men from India and one from Mauritania staying with them.

They could only greet them using signs because neither they nor she spoke English or French. They stayed for two months and then moved on to Chicago and New York.

Migrants cross the Suchiare river between Guatemala and Mexico. (Photo AP)

Tana cleans restaurants from 2am to 5am and at 7am she goes to her other job cleaning shopping centres until 6pm. When there is extra work, she goes to clean offices after her second job. On those days she gets only about three hours of sleep. At 1:45 am, she is already at the office, waiting in line with the other undocumented immigrants, from where they are taken by car to the different workplaces. They will be picked up later by those same cars. Tana works in a group; she doesn’t have a car but travels by train or bus.

Invariably, every week on Sunday morning, she will send money to the family in Guatemala. She has been following the same ritual for 24 years. With her remittances, her parents have managed to build a cement-block house with a terrace and are now adding a second floor. They have also opened a shop and built a cistern to store water when it arrives. They have enrolled her brothers in school. They all go to school because Tana made that a condition when she called them from the US two months after she left. All three of them simply must succeed in their studies.

Tana hasn’t eaten ice cream for 24 years; she doesn’t have a day off, working seven days a week. She buys all her clothes at a thrift store so as not to upset the remittances. She sometimes goes to her colleagues’ birthdays, but there is little money left for herself. She knows nothing of the parks, museums, swimming pools, cinemas or theatres and has never left Phoenix, where she lives.

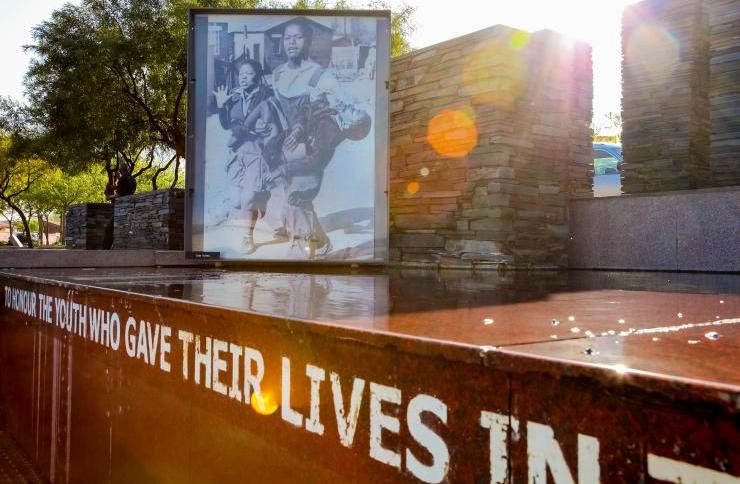

People shopping at the Great Mall©unitysphere/123RF.COM

But that day is her birthday, and she wants to celebrate it for the first time. She doesn’t want to go to work and wonders what it would be like not to turn up for work. She wants to put on a dress like the ones she wore in her native Camotán. She takes a deep breath, reaches out, fills herself with courage, and for the first time in 24 years she postpones sending her remittance. She has breakfast and goes to buy some material. She starts walking around the mall looking at the shelves; she had never seen so many things in the years she was cleaning. It is lunchtime and, for the first time, she buys herself a plate of Chinese food and then some pistachio ice cream. Walking on, she stops in front of a shoe shop. She enters and starts looking at the shoes. She never before bought herself new shoes, but always second-hand, like her clothes from the second-hand stores. She has never worn sandals because she saw them as a luxury to which she is not entitled. After walking around the store for three hours and battling feelings of guilt over spending the money on herself instead of sending it to Guatemala, she buys two pairs of shoes and a pair of sandals. So many doubts and feelings of guilt. Suddenly, she thinks that for her next birthday, her fortieth, she will also learn how to cook the cherry pies she sees in restaurant patisseries because from then on, she plans to always celebrate her birthday.

Ilka Oliva Corado