Books. Summer Reading.

Three interesting books for this summer.

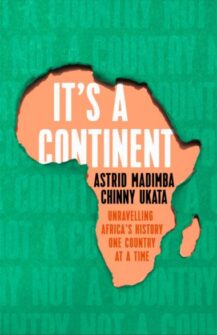

Why is Africa still perceived as a country when there are around 2,000 languages spoken on the continent alone?

The book It’s a Continent seeks to counter the misconception that Africa is a country by breaking down this vast, beautiful and complex continent into regions and countries.

Each of the 54 African countries has a unique history and culture, and this book highlights the key historical moments that have shaped each nation and contributed to its global position, as well as within the African continent. Each chapter (focusing on a different country) of the book brings to light stories and African figures that have been marginalised in mainstream education, in a humorous and easily-digestible format, breaking down facts and events that you wouldn’t believe happened.

Why is the Liberian flag so similar to the Stars and Stripes of the United States? Have you heard about Thomas Sankara’s quest for Burkina Faso’s self-sufficiency? African soldiers’ contribution to World War II? There are many aspects of history that mainstream education doesn’t address, and this book allows the reader to understand the consequences of historical colonial activities within the African Continent, and how many African countries continue to re-build. The majority of countries within the continent are young, not just in population but in age, as many only gained independence in the 20th Century.

It’s a Continent is the bold and brilliant book for readers who want to gain an understanding of things you were never taught in school.

Astrid Madimba was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo and grew up in the UK. She studies at University of Exeter. It’s a Continent is her first book. Chinny is British-Nigerian and studies at the University of Southampton. Her previous work has featured in publications including gal-dem and Black Ballad. It’s a Continent is Chinny’s first book.

It’s A Continent, Unravelling Africa’s History one Country At A Time, Astrid Madimba & Chinny Ukata, Coronet, 2022, London, 332 pages.

——————————–

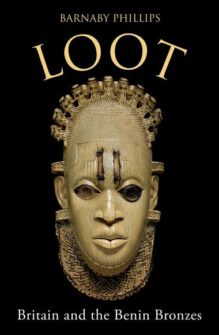

In 1974, the Nigerian government asked the British Museum to loan back an object that had been looted from the country more than seven decades earlier. That object, an ivory mask that once belonged to royalty in the Kingdom of Benin, depicts Idia, a queen active during the 16th century, and though it is cracked in parts, it retains its nearly unparalleled beauty. On its website, the British Museum calls the work “among the most enduring and emotive examples of the representation of women in Benin court art.”

“It’s a small thing, only twenty-three centimetres long, but I can’t look at it without feeling moved,” writes Barnaby Phillips in his new book Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes, a deep dive into the story of the Benin Bronzes. “The queen’s eyes are dark, inset with iron pupils and lids of bronze, making a lovely contrast with the aged ivory. She has a haunting feminine beauty.” It made sense that Nigerians wanted the mask to act as a mascot for a festival known as FESTAC ’77, a celebration of the continent’s culture. The British Museum rejected their plea “on conservation grounds,” claiming that the humidity in Nigeria would damage the work. In other words, the climate in which the mask was originally made would, in the eyes of the British, prove too hostile for it. Today, it is still housed by the British Museum, which has owned it since 1910.

Taken by British soldiers in 1897, these works, collectively known as the Benin Bronzes (though many are also crafted from ivory and brass), are held in institutions around the globe. Calls for their return are reaching a fever pitch, with Germany vowing to start sending back its Benin Bronzes next year. If these protests are relatively new among Europeans and Americans, they are old in Nigeria, where politicians, museum directors, artists, and local citizens have long pointed to the plundering of these works as a sign of colonialism’s long-term impacts on the region.But rarely have books like Loot focused so in-depth on the perspectives of Africans. As Loot makes clear, Nigerians have had a lot to say about the Benin Bronzes.

The ‘Benin Bronzes’ are amongst the most admired and valuable artworks in the world. But seeing them in the British Museum today is, in the words of one Benin City artist, like ‘visiting relatives behind bars’. In a time of huge controversy about the legacy of empire, racial justice and the future of museums, what does the future hold for the Bronzes?

Barnaby Phillips spent over twenty-five years as a journalist, reporting for the BBC from Mozambique, Angola, Nigeria and South Africa before joining Al Jazeera English. He is the author of Another Man’s War: The Story of a Burma Boy in Britain’s Forgotten African Army and Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes. He grew up in Kenya and now lives in London.

Loot, Britain and the Benin Bronzes, Barnard Phillips, OneWorld, 2021, London, 385 pages.

——————————-

This is a frantic, mystical journey through Africa’s biggest metropolis: Lagos. Going beyond the popular images of mad traffic or crowded slums, we learn of the incredible feats Lagosians pull off to survive their broken-down city, and the secret enabling them to cope with the chaos and precarity of Nigeria’s most populous centre: spirituality.

A female street fighter in a male-dominated mafia extortion business.

Two powerful chiefs locked in a deadly feud over billion-dollar real estate. An oil tycoon who gambles her fortune on televangelists’ prophecies. A rubbish scavenger dreaming of a reggae career.

A fisherman’s son trying to save Makoko, the ‘floating slum’, from demolition. A priestess to a river goddess selling sand to feed Lagos’s construction boom.

Belief in unseen forces unites these figures, as does their commitment to worshipping them–at shrines, in mosques and in churches.

In this extraordinary city, Tim Cocks uncovers something universal about human nature in the face of danger and high uncertainty: our tendency to place faith in a realm beyond.

Tim Cocks is a British-born journalist of South African parentage. Currently based in Johannesburg, he was formerly Reuters West & Central Africa bureau chief, based in Dakar, following four years in Lagos as Nigeria bureau chief. He holds an MA in Philosophy & Theology from the University of Oxford.

Lagos, Supernatural City, Tim Cocks, Hurst & Company, London 2022, 298 pages

(Open photo: 123rf.com)