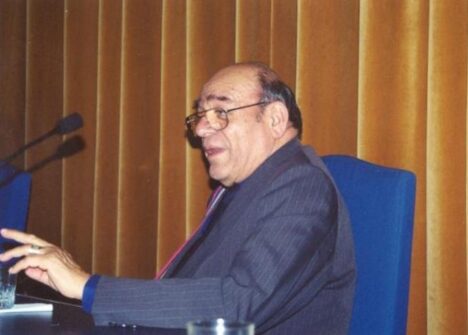

The renowned African theologian Prof. Fr. Laurenti Magesa died on 11 August, in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. “A giant of African Theology.”

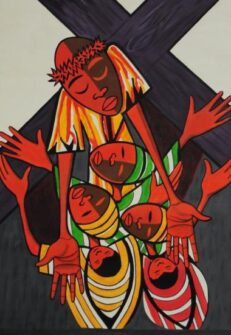

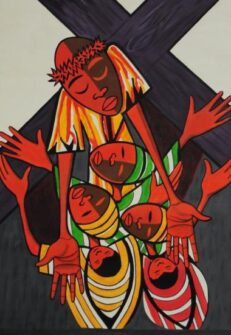

He was known as the pioneer of African Theology. Laurenti Cornelli Magesa grappled intelligently and faithfully with African existential contexts. He shared this mission with other African theologians: Jean-Marc Ela of Cameroon, Bénézet Bujo of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Bernardin Muzungu of Rwanda, Charles Nyamiti of Tanzania, and Agbonkhianmeghe E. Orobator of Nigeria. Magesa heard the Christological question of Jesus in the Synoptic Gospels: “And you, who do you say that I am?” (Mk 8:27+; Mt 16:15+; Lk 9:18+) and he felt the need for an intelligent and sincere African response.

In his farewell words at the funeral of Prof. Magesa, Bishop Michael Msonganzila of Musoma diocese to which Rev. Magesa was incardinated, summed up Magesa’s life with the following words: “Magesa kept asking Africans: And you, Africans, who do you say that Jesus is?” Isn’t this the substance of Magesa’s numerous writings? How can we characterize Magesa’s Magna Carta as found in What Is Not Sacred?

And what can I briefly say in a few words about Magesa beyond what his books say about him?

In The Post-Conciliar Church in Africa: No Turning Back the Clock (2016), Magesa examines the reception and rejection of Vatican II (1962-65) in the African Church. He invites his readers to realize that “this Council did not see itself as the end of a process, but rather as a beginning. It opened, not closed, doors – whether doctrinal or disciplinary – for ongoing reflection, for the possibility of ever-improving knowledge and understanding.” Magesa’s robust Ecclesial vision offers a stimulus for African (Catholic) Christians to keep reflecting deeply and implementing the message and treasures of the Council. He invites his reader to grasp “the scope, meaning, and implications of the Council for the Church and people of Africa.”

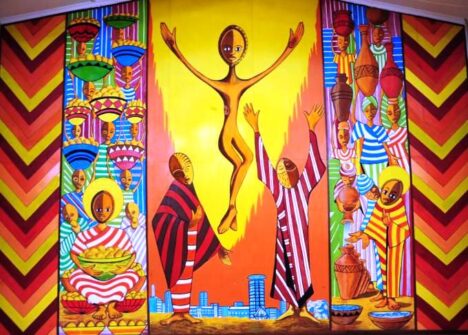

African Spirituality

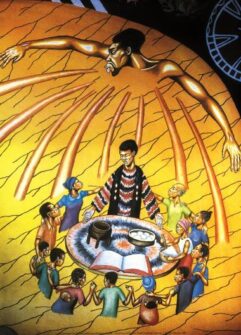

In one of his most notable and brilliant writings, What Is Not Sacred? African Spirituality. Prof. Magesa explores “the beauty of the spirituality of African religion and its enduring gift to Christianity as a light, not a shadow.” Magesa pays theological attention to indigenous African Spirituality and Christian Inculturation in Africa and this is his book’s greatest gift. He wrestles intelligently with important theological questions as they pertain to African life, such as the nature of God, revelation, and the meaning of life itself. Some scholars have taken Magesa’s What Is Not Sacred? as the Magna Carta of African Theology. Indeed, he makes it clear that “The African understanding of spirituality can be seen as human participation in the total, universal existence, the whole of human existential experience in the world” (p. 40).

He explains that there is no experience devoid of God’s self-communication, that is devoid of grace. Whatever exists, does so because of God’s grace. No one can live life without the experience of that grace. Here Magesa joins the German Jesuit theologian, Karl Rahner’s concept of “Uncreated Grace.”

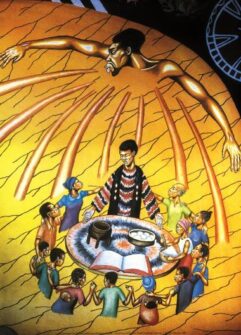

Every human experience is an encounter with grace. In this Magna Carta, Magesa awakens Africans and all who read him from their dogmatic slumbers and enlightens them with the understanding of important themes in Africa’s spiritual patrimony. His major concern is to show how underestimating this patrimony “has weakened the impact of the missionary endeavor of evangelization on the continent … He laments the fact that the traditional African spiritual worldview, which should have been the cornerstone in building a Christian edifice, is deeply rooted in the culture of its recipients, was disregarded.” He exposes the treasures of African spirituality and relates them to the supernatural. He invites the African to enter into communion with the empirical world which is transcendental and sacramental.

He describes the different ways in which the traditional understanding of life shapes the attitudes of the African. For Magesa, “there is an inter-connectedness between life and the transcendental that forms the spiritual model of the African mindset.”

Magesa’s pedagogy, obvious in What Is Not Sacred, is to assist the reader to discover or at least to have a sense of what African Spirituality can offer to deepen Christianity rooted in the cultural heritage of Africa. Magesa’ writings demonstrate with clarity that for anything to be considered truly Christian in African Christianity, it should be born and rooted in the African indigenous approach to God and to the message of the Gospel. Any attempt to circumvent this path by using one not born into the African cultural patrimony is doomed to fail. “Other spiritual traditions can inspire but cannot replace the basic shape of African spirituality” (What Is Not Sacred, p. 107).

Tanzania. Two young maasai warriors in traditional dress are standing in the savannah and talking to each other. One holds a ritual horn. 123rf.com

The implications of this Spirituality are tremendous. For Magesa, particular attention to African Spirituality can further the promotion of justice, good governance and interreligious dialogue. Magesa uses the “Ubuntu factor” to stress the quality of relationships between humans and nature, to prioritize tolerance, respect and coexistence in those places where reconciliation is still unattainable. Our mutual dependence and cooperation must promote social inclusion as opposed to “unhealthy competition and obsession with individual accomplishments, which are often attained at the expense of the well-being of others or the environment” (150). What is Not Sacred is Magesa’s enduring legacy. Tolle et lege (take and read), if you desire to have some key glimpses of Magesa’s hopes and joys, pains and anguish in What is not Sacred? African Spirituality.

Of particular note is that some African theologians have equally named his Anatomy of Inculturation: Transforming the Church in Africa (2004) as the Magna Carta of African Theology of Inculturation.

For further insight into Magesa’s academic biography, let me also share, albeit in an illustrative way, his authored books which can inspire present and future readers’ attention. African Religion in a Dialogue Debate: From Intolerance to Coexistence (2010); Rethinking Mission: Evangelization in African in a New Era (2006); Anatomy of Inculturation: Transforming the Church in Africa (2004); Christian Ethics in Africa (2002); Le Catholicisme Africain en mutation: des modèles d’église pour un siècle nouveau (2001); African Religion: The Moral Traditions of Abundant Life (1997), translated in German as Ethik des Lebens: Die afrikanischeKultur der Gemeinschaft; and The Church and Liberation in Africa (1976). Prof. Laurenti Magesa also co-authored others books: How Theology Serves: Reflections on Professor Peter Kanyandago’s Contribution to African Theology. (2021); Democracy and Reconciliation in African Christianity (1999); The Church in African Christianity (1990); Jesus in African Christianity (1989); and African Christian Marriage (1977). What often stands out in his authored and co-authored works, which always focused on Africa, is that Magesa’s study of African Christianity is that “although religion in the African mindset provides solutions to almost everything that concerns human life, Christianity has not been presented and received that way. Inculturation is therefore not an option but a necessity.”

Magesa published over two hundred articles in various peer reviewed academic and popular journals and as a chapter-contributor in books since 1975 to his death on August 11, 2022. Magesa received numerous awards, notably PhD Honoris Causa from DePaul University, Chicago, USA in 2018; US Mission Award as Distinguished African Theologian in 1998; and Xavier Univeristy’s J. Bruegeman Chair Award in 1995.

A man of God

Magesa was not just an erudite author of books. He was a friend to many. He was recognized as a man of God to those who met him. He was a pastor for God’s people. He did not seek self-aggrandizement. He was a self-effacing man with unparalleled humility. He taught me that the true value of things is not found in ostentation, but in letting your work speak for itself. Magesa rejoiced whenever he learned of his students’ small accomplishments. He rejoiced as if they were his own and celebrated them with great joy and happiness. When I returned from Boston, USA after having completed my Doctoral Studies, Laurenti took me to a beautiful place to be at ease and relax. From there we went to Serengeti National Park. He did the same for many others. When I was invited to speak at the United Nations General Assembly Hall, Laurenti edited my speech and offered wise advice. His wisdom shared with me, will remain engraved in the archives of the United Nations.

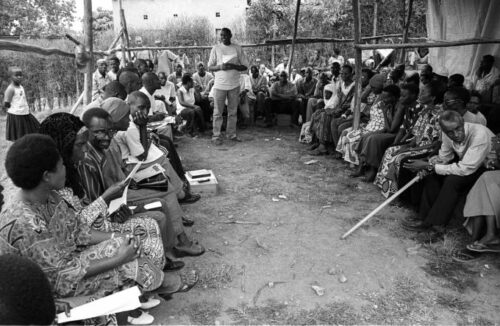

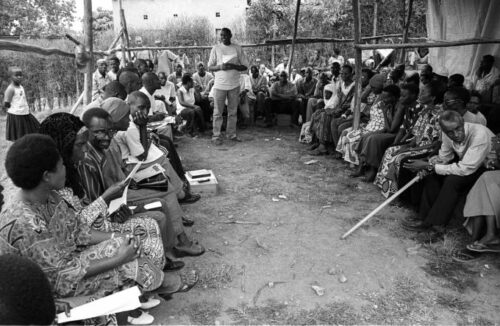

I invited Laurenti to speak at a conference in Rwanda at which he presented a brilliant paper which will be part of a forthcoming book published by Georgetown University Press (2023). The title of his paper is “Learning from a Tragedy: Toward a New Evangelization after the Genocide in Rwanda.” He stated that for about three months in 1994 – between April and mid-July – a systematic massacre of upwards of 800,000 people, mostly ethnic Tutsis, took place in Rwanda in what has become known universally as the Genocide against Tutsi.

Magesa was clear that there should not be any form of moral equivalence between a civil war and a genocide, as many tend to do when it comes to Rwanda. These are entirely different and should be honestly treated differently. It is globally recognized as well that the Catholic Church at various levels was involved negatively in that drama: in its questionable historical methods of evangelization, which created and cemented unnecessary divisions among the Rwandan people, on the one hand, and during the tragedy itself by abetting the violence in some significant cases on the other. If this scar on the church in Rwanda cannot be wiped away completely, it is necessary to learn from it so that it should not be repeated. Such was the essence of his presentation. He emphasized the necessity of memory in acknowledging guilt and repentance for the role the church inadvertently or knowingly played in the sad narrative of the genocide. Most importantly, he suggested that lessons to be learned from the genocide experience should be a basis for a “new evangelization,” not only in post-genocide Rwanda, but for the wider Church in the African continent and, indeed, throughout the world. Here, he joins other theologians such as Emmanuel Katongole who writes that the ecclesial experience of the genocide in Rwanda is a “mirror” to the universal Church.

The challenge for the church in Rwanda at all levels is to discern what is of God, and to establish practices for evangelization and catechetical approaches that will support justice, foster genuine universal reconciliation and lasting peace. As Pope John Paul II said similar words in Pastores Dabo Vobis, “Today, in particular, the pressing pastoral task of the new evangelization calls for the involvement of the entire People of God, and requires a new fervor, new methods and a new expression for the announcing and witnessing of the Gospel.” For this, a new type of leadership is called for: among other things, it “demands … a fruitful cooperation with the lay faithful, always respecting and fostering the different roles, charisms and ministries present within the ecclesial community.”

His Legacy

In November 2021, it became clear that Laurenti could not be the keynote speaker for a webinar on the Synod on Synodality organized by the Symposium of Episcopal Conference for Africa and Madagascar (SCAM) and the Jesuit Conference of Africa and Madagascar (JCAM). This was because his excruciating cancer. Laurenti suggested my name to the conveners of the webcast and he also called me on his phone and said: “Fr. Marcel, you have to do it and I believe you can carry on this work.” Despite his pain, Laurenti followed my speech and he was the first to congratulate his student. In his final days, he urged me to publish a book about Rwanda which he prefaced and also proposed its title. He did this while he was dying from metastasized pancreatic cancer. The book Risen from the Ashes: Theology as Autobiography in Post-Genocide Rwanda will be available in November 2022. With all this, together with others who share my sentiments because of what Laurenti had done for them, we can safely say that we have lost a father, a brother, a friend, a mentor and a giant of African Theology. Our hope in the Risen Christ is that Laurenti is now interceding for us and that we carry on his legacy which is now left in our hands.

Among many enduring lessons from Laurenti and beyond his scholarship, he taught us that when you know what you are passionate about, few things will be a barrier if you really want to be of service to humanity. He was passionate about Jesus Christ not as an abstract idea, but as a person whose message must be rooted in hearts of Africans. For Laurenti, the place where western Christian structures have failed to tap into African religious values has been in the former’s tendency to see repentance and spiritual transformation as an almost exclusively “personal,” and “inner” endeavor, ignoring the role of the community which, for the African, is pivotal. Social processes of community building, especially across existing divides caused by human wrongdoing, are for the African family very much transformative, as important and as necessary as interior attitudes of repentance.

Additionally, Laurenti knew that he had received much from his scholarly mission, and in return for all he received, he gave generously of himself. He was convinced that, “If you hold on to your life, you lose it, if you give it away, it becomes ever lasting life!” (Mt 16:25). He understood that if we are going to exist, we must give ourselves away. There may be no better way of doing that than spending many years teaching and journeying with students, and forming men and women well for the future Society of Jesus and the Church. He himself did this perfectly.

He gave himself away. He knew his own limitations, but they did not become a barrier. When I accompanied him to Musoma, Tanzania on his last journey, after he retired from Hekima University College, I asked him: “What made you a prolific writer?” He responded. “I am not a great speaker like you, but I hope my writings are my speech.” Two weeks before he died on August 11, 2022, a day after his 76th birthday, I called him and he was with his brother, Prof. Evaristi Cornelli Magoti and very much at peace. He gave me several bits of wisdom and advice. Before I left for another meeting, he said this: “I conclude with a piece of advice. It is important not to be a burden to yourself as a priest, doing things simply out of duty. This will eventually crush you. But even more important: try not to be a burden to others on account of your own discontents in life.”

In his Tribute to Laurenti Magesa, which was published by The Tablet (August 20-27, 2022), Agbonkhianmeghe E. Orobator could not have been more right. “The belief is strong in many parts of Africa that the status of an ancestor is reserved for people who have made a transformative and enduring contribution of service to their community. By his life of service as a pastor, the depth of his scholarship and the example of his life as a Christian, Magesa now qualifies to join the ranks of ancestors of the Church in Africa and the universal Church.”

Marcel Uwineza, SJ, PhD

Dean, Jesuit School of Theology

Hekima University College

Nairobi, Kenya