World Youth Day. Pope Francis: “All together in Lisbon! A new beginning for the young and for humanity”.

“I hope and I firmly believe that the experience many of you will have in Lisbon next August will represent a new beginning for you, the young, and – with you – for humanity as a whole”.

The World Youth Day will be celebrated in particular Churches on November 20 next and at international level from August 1 to 6, 2023 in Lisbon with the theme “Mary arose and went with haste” (Lk 1:39).

Pope Francis comments: “In these troubling times, when our human family, already tested by the trauma of the pandemic, is racked by the tragedy of war, Mary shows to all of us, and especially to you, young people like herself, the path of proximity and encounter”.

Francis writes in the Message for the XXXVII World Youth Day, which highlights a verb in particular – to arise – whose meaning includes that of “waking up to the life all around us.” After the Annunciation, “Mary could have focused on herself and her own worries and fears about her new condition. Instead – points out the Pope – she arises and sets out, for she is certain that God’s plan is the best plan for her life.”

Thus “Mary becomes a temple of God, an image of the pilgrim Church, a Church that goes forth for service, a Church that brings the good news to all!”. Mary in particular “is a model for young people on the move, who refuse to stand in front of a mirror to contemplate themselves or to get caught up in the “net”.

Mary’s focus is always directed outwards. She is the woman of Easter, in a permanent state of exodus, going forth from herself towards that great Other who is God and towards others, her brothers and sisters, especially those in greatest need.” “Each of you can ask: ‘How do I react to the needs that I see all around me? Do I think immediately of some reason not to get involved? Or do I show interest and willingness to help?”, is Francis’ question to young people.

“To be sure, you cannot resolve all the problems of the world – comments the Pope – Yet you can begin with the problems of those closest to you, with the needs of your own community”, following the example of Mother Teresa.”

Francis points out: “How many people in our world look forward to a visit from someone who is concerned about them! How many of the elderly, the sick, the imprisoned and refugees have need of a look of sympathy, a visit from a brother or sister who scales the walls of indifference! What kinds of “haste” do you have, dear young people?”

“What leads you to feel a need to get up and go, lest you end up standing still? Many people – in the wake of realities like the pandemic, war, forced migration, poverty, violence and climate disasters – are asking themselves: Why is this happening to me? Why me? And why now? But the real question in life is instead: for whom am I living? The haste of the young woman of Nazareth is the haste of those capable of putting other people’s needs above their own.”

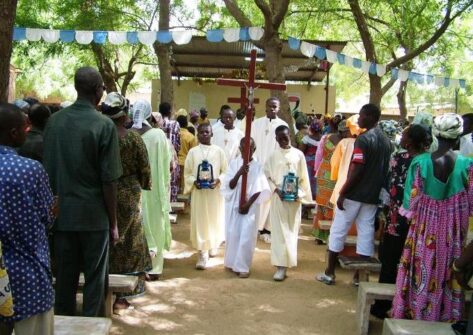

Francis goes on to note: “How many testimonies have we heard from people who were “visited” by Mary, the Mother of Jesus and our Mother! In how many far-off places of the earth, in every age – through apparitions and special graces – has Mary visited her people! There is practically no place on earth that she has not visited.”

A “healthy haste”, points out the Pope, “drives us always upwards and towards others.” Yet there is also an “unhealthy haste, which can drive us to live superficially and to take everything lightly. Without commitment or concern, without investing ourselves in what we do. It is the haste of those who live, study, work and socialize without any real personal investment.”

“This can happen in interpersonal relationships – argues the Pope -. In families, when we never stop to listen and spend time with others. In friendships, when we expect our friends to keep us entertained and fulfil our needs, but immediately look the other way if we see that they are troubled and need our time and help. Even among couples in love, few have the patience to really get to know and understand each other. We can have the same attitude in school, at work and in other areas of our daily lives. When things are done in haste, they tend not to be fruitful. They risk remaining barren and lifeless.”

Finally, Francis returns to highlight the importance of dialogue between generations: “to bridge distances – between generations, social classes, ethnic and other groups – and even put an end to wars.”

“It is no coincidence that war is returning to Europe at a time when the generation that experienced it in the last century is dying out,” is the Pope’s analysis: “We need the covenant between young and old, lest we forget the lessons of history; we need to overcome all the forms of polarization and extremism present in today’s world.”