Nigeria.Oil theft is sinking Africa’s first economy.

Whereas other oil producers are boasting from substantial revenues as a result of high crude prices triggered by the Ukraine war; theft, shut-ins and lack of investment are hitting badly a sector which represents, 89 percent of Nigeria’s export revenues and more than 50 percent of the national budget.

Last August, Nigeria faced a record low production of only 980,000 barrels a day, well below its OPEC quota of 1,55 m b/d. The figure calculated by the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries corresponds to half of Nigeria’s export capacity of 2 million bpd.

As a result, Nigeria once Africa’s first producer dropped to the fourth rank, behind Angola, Algeria and Libya.

On the 9 September, President Muhammadu Buhari said such decline was putting the economy in a precarious situation. Crude oil exports accounted indeed in 2021 for 89 percent of Nigeria’s export revenues and for more than 50 percent of the national budget.

Nigeria President Muhammadu Buhari. CC BY-SA 4.0/Bayo Omoboriowo

According to Nigerian officials, the main cause for this decline is theft which is carried out at an industrial-scale. It poses an “existential” threat to the sector, claims a Shell executive. Theft and the related sabotage of pipelines by criminal gangs to siphon the crude are causing a loss of more than 200,000 barrels per day, according to the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC).

In August 2022, the NNPC claimed that up to 700,0000 bpd were missing from its exports as a result of theft and of the decision by oil companies operating locally to shut operations to avoid the thieves. Some companies reported even that 80 percent of the oil they put into pipelines was stolen. And the situation can still deteriorate since oil workers unions threaten to call for a strike if the government does not take action against the oil bunkering gangs.

The NNPC estimated in early September that losses may reach up to US $ 700 million per month which represents the equivalent of $ 8.4 billion per year. The Nigerian Extractive Industries and Transparency Initiative estimated that Nigeria lost, between 2009 and 2018, $ 42 billion owing to oil theft and its consequences; The figure is higher than Nigeria’s external debt estimated at $ 39 bn by March 2022.

Headquarters of Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation. It is government oil company. CC BY-SA 4.0/ Simoniwodi

In an interview with the French daily Le Monde, Alexander Sewell, researcher for the Stakeholder Democracy Network (SDN), which supports local populations affected by the extractive industries, describes two methods to steal oil.

The first consists in diverting oil from a pipeline to convey it by smaller pipes to barges which in turn, can either supply local refineries or bring the crude to larger vessels which can head out to the sea in order to refuel a tanker that can sail directly to South America, Europe or Asia or transfer its cargo to other vessels on the high seas.

The authorities claim to clamp down on perpetrators. In June 2022, the Special Anti-Vandal Unit of the National Security and Civil Defence Corps (NSCDC) arrested 88 people accused of having caused pollution and health hazards posed by illegal refining. But sources in the Niger Delta say that bunkering cannot stop because the military, the police and even the NSDC are involved. Some speak of a “sophisticated mafia of powerful Nigerians and foreigners”, including government officials, retired oil industry personnel, politicians and businessmen. In 2019, the governor of Rivers state himself, Nyesom Wike confirmed that top military officers were involved and sponsoring oil bunkering. The damage inflicted by small-time oil bunkers in Rivers, Delta, Bayelsa and other states, is peanuts compared with the havoc caused by the cartels that own giant vessels and equipment.

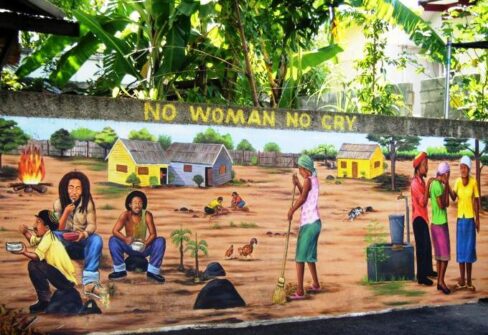

Woman walking on the Shell oil pipelines.

The second technique of stealing, called “topping”, is far more difficult to detect and even more damaging. It consists in adding undeclared crude to a shipment for which the export permits have been issued, allowing traffickers to resell the extra oil without being noticed. International oil companies involved in this business pay no royalties on the crude illegally bunkered, says a report from the British Chatham House Institute. Perpetrators benefit from official protections. According to Sewell, sometimes, the ships transporting this stolen oil through the Niger Delta are even escorted by the military.On top of that, the bunkering cartels have huge means. On the 25 August 2022, President Buhari’s Special Assistant on Digital & New Media, Tolu Ogunlesi reported that the MT Heroic Idun, a very large crude carrier registered in the Marshall Islands, owned by the Norwegian company Hunter Tankers AS and operated by the Dutch-based company Trafigura, with a capacity of 3 million barrels of crude, entered Nigerian waters a fortnight before with “the obvious intention of lifting crude illegally.”

The tanker was then asked to follow a Nigerian Navy ship to Bonny anchorage pending when she would be cleared for loading. But the tanker “refused to cooperate” and fled southwards in a bid to evade arrest. Moreover, the tanker made a false broadcast to the International Maritime Bureau alleging it was under attack by pirates. Eventually, the vessel was seized in the Equatorial Guinea waters.

Motor Tanker (MT) Heroic Idun. Photo: af24news

This failed attempt is just one example of the large-scale theft orchestrated by Nigerian and foreign big players. According oil firms and Ministry of Petroleum estimates 90 percent of the oil snatched is sold on world markets while only 10 percent is refined locally by gangs operating in the creeks and swamps of the Delta.

This high scale theft has led the NNPC to raise the issue with the European Union. In July 2022, the EU promised to work with Nigeria to help tackle oil theft and the illegal refining menace after a fact-finding mission in the Niger Delta of the European Commission Deputy Director General on Mobility and Transport, Mathew Baldwin. According to former presidential advisor, Dele Cole, the main buyers of Nigerian stolen oil are organised criminal networks in the Balkans and refiners in Singapore.

In a report entitled “Nigeria’s Criminal Crude”, the London-based Chatham House policy institute estimated that much of the proceeds of Nigeria’s stolen oil were laundered in Britain, United States, Dubai, Indonesia, India and Switzerland. The US, Brazil, China, Thailand and Indonesia are the other likely destination of the stolen crude.

The stolen oil which goes to local refineries operated by local gangs is being processed in extremely poor safety conditions. In April 2022, more than 100 people were burned alive in the explosion of an illegal refinery in the Abaezi forest between Imo and Rivers, in South-eastern Nigeria.

However, observers on the spot don’t believe this trend will end anytime soon since there are social and political reasons behind the importance of the illegal bunkering and refining, despite the industrial accidents and the pollution caused by these activities in farmlands, swamps and rivers. Some communities even justify their practices. A local oil refiner told the SDN that “the government and oil companies are collecting our oil, and we don’t have jobs, no money, so we have to collect the oil and refine our own”. Such industry fills an economic vacuum where local communities suffer the negative impacts of oil extraction but see none of the economic benefits since the Federal State fails to provide basic public services and security.

Yet, the sharp decline of Nigeria’s crude oil production and exports is not only owed to theft, argues Nigeria’s Chief of Naval Staff, Vice Admiral Awwal Gambo who disputes NNPC’s oil theft figures of 200,000 to 400,000 barrels per day. According to Gambo, the government makes the mistake of calculating losses due to force majeure as well as shut-ins as part of oil being stolen.

François Misser