Madagascar. Soatanana. The “City of Goodness”.

The Churches of the Awakening were born in the Pentecostal sphere, they have experienced a boom since the 1990s, but on the Red Island, there is an ancient one that remains close to the spirit of its origins.

In the central highlands of Madagascar, not far from Fianarantsoa, the capital of the Haute Matsiatra region, lies the town of Soatanana, a toponym that translates to “City of Goodness”. This rural community, immersed in a landscape of green hills and crystal-clear waterways, is the hub of Fifohazana, a Christian religious movement that has shaped Malagasy spirituality for over a century. In this remote corner of the large island in the Indian Ocean, a silent spiritual revolution is taking shape at the hands of “white shepherds”, so called because of the white linen tunics they wear as a distinctive sign of purity and dedication.

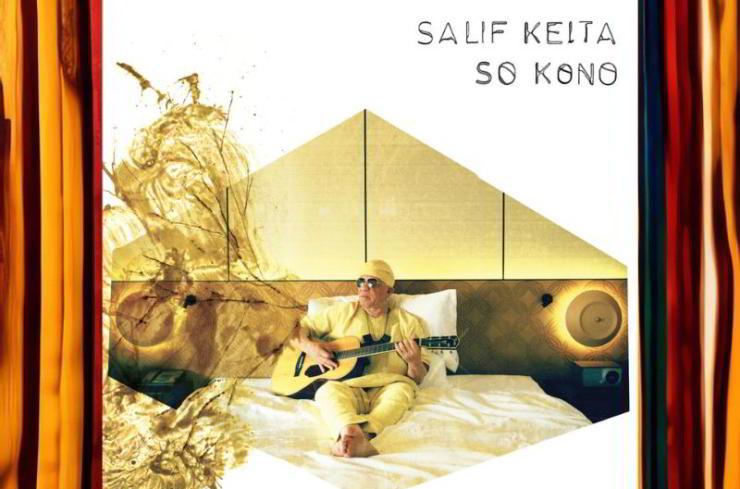

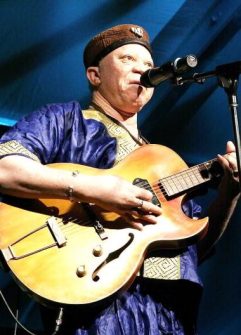

The Fifohazana movement, a Malagasy term that means “awakening”123rf

The Fifohazana movement, a Malagasy term that means “awakening”, is rooted in a succession of movements of spiritual rebirth that animated Madagascar between the end of the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth century following those same awakenings that periodically crossed the history of the Protestant world. Its origin is linked to the figure of Rainisoalambo, a traditional healer converted to Christianity by some Norwegian missionaries.

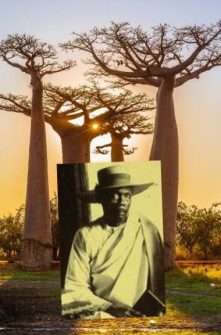

The dream of Rainisoalambo

The story goes that when the first European pastors began to settle in the region – they wore clothes of very different make from those the locals were used to, were paid to teach the new faith and were not subjected to forced manual labour – Rainisoalambo, an ambitious man, began to desire their way of life, thinking that he could live like them if he became a pastor. So, he studied and in 1884 was baptized, even though he had not abandoned pagan practices in the meantime, in the hope of becoming rich. After a six-month course of Bible instruction, he was appointed an unpaid catechist in the local church and then, disappointed, returned to his former work as a farmer and healer/fortune teller.

Dada Rainisoalambo, the founder of Fifohazana movement. File Archive

At that time, the standard of living in remote villages like Rainisoalambo was very low, and when famine and an epidemic of smallpox and malaria struck the region, killing many inhabitants, incantations and pharmacopoeia were no remedy for poverty, malnutrition and disease. Rainisoalambo’s family was decimated and he too became gravely ill, his body covered with painful sores that made it impossible for him to work. From the depths of his misery and despair, Rainisoalambo then invoked the God he had learned to know. That same night, October 14, 1894, according to his testimony, he had a dream. He saw a man, completely dressed in white and bathed in light, standing next to him, ordering him to throw away his amulets and other objects he used for divination. The next day at dawn he carried out the order and immediately felt freed from pain. According to his account, Jesus had lifted him from the depths of the pit and freed him from his pagan chains. Since he knew how to read, he began to study the Bible again, but more carefully, especially the New Testament. He already knew something about prayer, church rites and the Christian community: after spending many weeks meditating on the Scriptures, he began to spread his message. He turned first to his family and friends since many of them were sick and practised the ancestral religion.

Rainisoalambo’s first disciples began to live in community and pray together. 123rf

The central theme of his preaching was that they should turn away from idolatry and cling to Jesus Christ, who had appeared to him and spoken to him. He said that if they wanted to be healed, they should get rid of their fetishes. Many followed the advice and were healed. Then he went to the nearby villages, visiting and praying for those who were so sick that they could not even pray. He laid his hands on the sick, proclaiming that Jesus was the source of all healing, and they were healed.

Life in community

The news of the healings spread quickly, and more and more sick people and their families sought out the man who preached Jesus Christ. Rainisoalambo’s first disciples began to live in community, praying together and taking on a series of solemn commitments: learning to read and count, so that they could read the Bible themselves; keeping their homes and yards clean; having a separate kitchen area so that the home could be used to gather and honour God; cultivating a garden and thus having a source of food; and always beginning every activity with a prayer in the name of Jesus.

The Malagasy Church of the Awakening represents, for historians of religions, a true model of that process of indigenization. 123rf

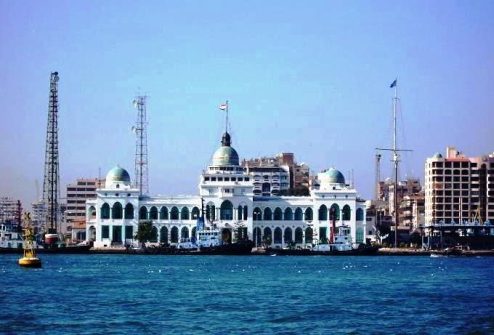

They also decided that at funeral ceremonies, which were often an excuse for drunkenness and pagan debauchery, beautiful clothes should be worn, and there should be singing, prayers and exhortations, but no slaughter of livestock, so that the grieving family would not become impoverished on such occasions. They preached the Gospel, healed the sick and freed the possessed. To keep the Bible with them at all times, they created white cotton bags to carry over their shoulders. Initially, the community met in Rainisoalambo’s home village of Ambatoreny, but in 1902, with the changing political climate and the increased control imposed by the French colonial authorities, the “revival centre” was moved to Soatanana, where it still is today, to place itself under the aegis of the Norwegian mission and be integrated into the Lutheran parish.

The New Jerusalem

Thanks to Rainisoalambo, the community of Soatanana has become the centre of spiritual awakening and for this reason it is also called “New Jerusalem”. Here, the principles of Fifohazana are still practised daily: collective prayer begins and ends the day, and the work ethic is reflected in the commitment to agriculture, livestock farming and artisanal activities, calling for a radical change of life, far from the plagues of modernity, consumption and jealousy. The feet of every foreigner, vahaza in Malagasy, who enters the village are washed and the entire life of the community, which today has about five thousand members, aspires to adhere to an inflexible practice of the precepts of the Bible. The “white pastors” of Soatanana embody the spirituality that

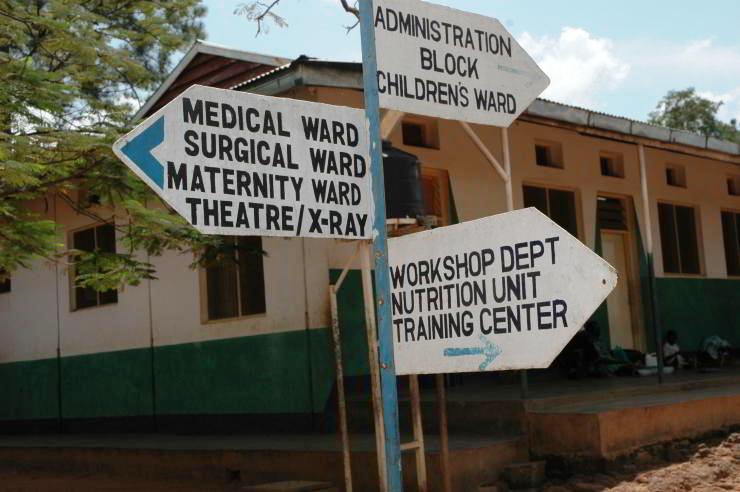

Soatanana is under the aegis of the Norwegian mission, and it is integrated into the Lutheran parish. 123rf

Rainisoalambo wanted to transmit and aim in this way to represent a model of active and authentic Christian life. Their existence is dedicated to service, following principles of love and mutual aid and calling for a radical change of life, far from the plagues of modernity, consumerism and jealousy. And every year, around mid-September, the country comes alive even more, on the occasion of the annual gatherings of the movement that attract pilgrims from all over Madagascar, and represent moments of strong spiritual sharing in which adherents of other evangelical awakenings also take part. These are the events, in fact, that not only strengthen the Fifohazana community but also aim to spread a message of peace and reconciliation, testifying to the transformative impact of faith on daily life. Today there are numerous examples of independent Christian communities in many African countries, but the Malagasy Church of the Awakening represents for historians of religions a true model of that process of indigenization that, thanks to the translation into a canon that is understandable and acceptable to the wider local population, has allowed the propagation of the Christian faith even in the most remote areas of the continent. (Open Photo: Disciples of the white shepherds of Soatanana in their Sunday procession. 123rf)

Santatra Ramanantsoa