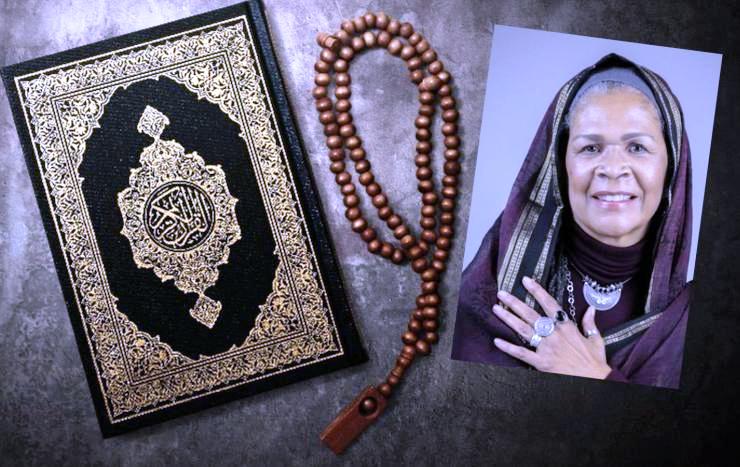

Amina Wadud, one of the most important theologians of Islam, criticizes the Islamic patriarchate, the male Imamate and the patriarchal interpretation of the Koran.

The recent demonstrations in Iran show how important it is to give women a voice in the Islamic world.

She is one of the most listened to and, at the same time, most provocative voices of Islamic feminism, which challenges both political and religious Muslim patriarchy with gestures that do not leave indifferent the followers of Islam and especially the religious leaders, who are divided into two camps: those who criticize her defiant behaviour and anathematize it – the majority – and those who support it and share its egalitarian exegesis of the Koran and its feminist claims – the minority. In March 2005, Wadud made international headlines when leading Friday prayers in a mixed congregation in New York, she sparked controversy in some spheres of the Islamic world.

During the prayers, she affirmed that “the issue of gender equality is very important for Islam. Unfortunately, Muslims have given a very restrictive interpretation of history and moved backwards. With these prayers, we want to take a step forward”.

That same year, she again led the prayers in a mixed assembly in Barcelona during the 1st Congress of Islamic Feminism.

The reactions of the Ulamas were not long in coming. Sheikh Yusef al-Qaradawi of Qatar issued a fatwa against Wadud appealing to the woman’s body, “whose physique naturally constitutes a provocation to the instincts of men”. In it he condemned Amina as anti-Islamic and heretical, and the participants in prayer as accomplices.

Sabed Tantawi of Cairo declared mixed prayer invalid, arguing that men should pray with humility and modesty, and never in the presence of a woman.There have also been favourable reactions from Muslim intellectuals and academics, such as Egypt’s Gamal al-Banna, Pakistan’s Javed Ahmad, who saw in Wadud’s gesture a revolutionary change in Islam that has the support of Islamic sources and that would have repercussions around the world.

The female voice must not only have full expression, but sometimes it will also have to have primacy,” Photo: Glen Halog (CC BY-NC 2.0)

At the same time, the response of Islamic feminism was not long in coming; neither in the Koran nor in the hadith is there a single text that prohibits women from leading prayer in a congregation of men and women. If a woman is trained to give a Friday sermon in the mosque, why can’t she do it? If a woman is chosen by the community, why will she not be able to lead community prayer?

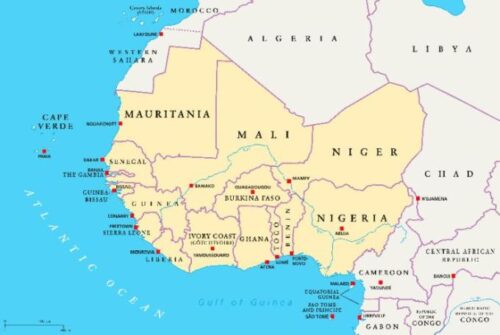

Amina Wadud’s subversive gesture led to an in-depth reflection on the issue and to the further recognition of the female Imamate in different Muslim communities in South Africa, North America, and Europe. The Muslim Educational Centre in Oxford, England, organizes mixed prayers in which a woman imam preaches.The Tawhid Mosque network, created in the United States by the Association of Muslims for Progressive Values (MPV), founded by Indonesian imam Anni Zonneveld, supports inclusive Islam in favour of gender equality. The mosque in Washington is run by gay imam Daayiee Abdullah.

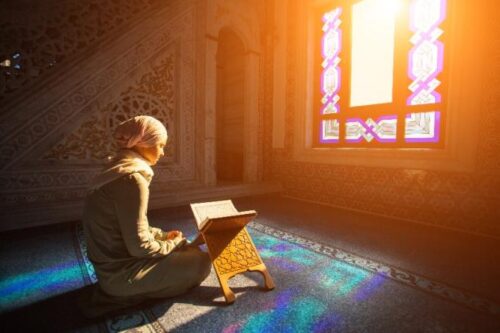

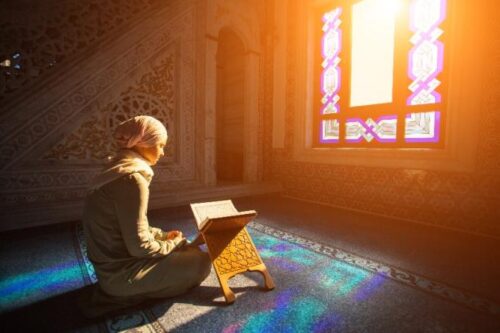

Muslim women reading Koran in the mosque during the Ramadan. (Photo: Freepik)

In November 2012 the Association of Progressive Muslims of France (MPF) created the first inclusive mosque, linked to the aforementioned North American network of Muslims for Progressive Values, who celebrate Friday prayers without any discrimination, gender, sexual orientation, or ethnicity.

Amina Wadud believes that the era of patriarchy is over. “We must evolve – she says – towards another more tolerant and cooperative model, because it is not only the future of Islam that is at stake, but the very future of the planet. In order for our families, communities and nations to move forward, more and more women must reach the areas of progress”. In defence of the new egalitarian and cooperative model, she cites the Koran, since it “argues that men and women were created inequality”. In her opinion, the principles of the Prophet have been distorted. There has been a ‘functional shift’ of Islam to conform to male domination. Precisely the movement contrary to what happened in the origins of the Muslim religion.

A feminist reading of the Koran

The Muslim theologian’s research is aimed at recovering the voice of women in the Koran and their word as commentators on the text, with the dual objective of challenging the intellectual tendency of Islam that marginalizes the female voice in the sacred text and its interpretation and to expand the possibilities of understanding among Muslims themselves. Wadud starts from an indisputable fact: the voice of women has been silenced in the Koranic text by its interpreters and has been absent from the intellectual heritage of Islam. Only men have been considered people with full rights to the presence of God and as leaders of women, while women are nothing more than mere extensions of men.

People in the Holy Shrine of Lady Fatima Masumeh, in Qom, Iran. Lady Fatima Masumeh was the sister of Imam Reza, one of the twelve imams in Islam. Photo: 123rf.com

Moreover, such silence is understood by Muslim thinkers themselves as part of a divine decree and God’s will. Women themselves have voluntarily accepted this situation of marginality for centuries, even when they have been forced to deny equality in their human condition and to accept their exclusion from the koranic text.

To this silence must be added another equally negative element for Islam: with the exception of the last three or four decades, almost no substantial exegesis of the Koran has been produced by women.

However, Wadud notes, the voice of women is contained in the Koran and makes a fundamental contribution when it comes to commenting on and interpreting it. And the search for that voice includes the person of the son-in-law, that is, the woman: “The female voice in the Qur’an is the voice of Allah, and it is not a woman, nor is it feminine. He’s not even a man, and neither is he masculine. Both the male and female voices are the divine enterprise of making themselves known through the text”.Another thing is patriarchal – or rather, anti-intellectual – intellectual heritage of Islam, which certainly privileges the male voice, the qualities and attributes of God related to power and even violence, when other qualities and attributes are more important, as shown by the 99 most beautiful names for God in the Koran: the life-giver, the merciful, the kind, the generous, the tender, the grateful, the trusting, the protector, the patient, the indulgent, the just, etc.

Amina believes that it is necessary to emphasize the female voice today to achieve balance. During the fourteen centuries of Islam, it was almost exclusively men who wrote treatises on exegesis, considered authoritative and definitive.

By silencing the female voice of the text, the Islamic ethos limited the richness of the text, which constitutes, in its view, an injustice against the divine author of the text and against those who seek in it moral guidance. To broaden the moral horizon of the text, it is necessary to eliminate the unique interpretative authority of men, recover the female voice within the Koran and encourage the development of feminist commentaries. “The female voice must not only have full expression, but sometimes it will also have to have primacy”, says Amina.

Another Koranic argument to which the Muslim theologian appeals to defend the equality of men and women in the sacred text is the idea of the duality of all creation. Men and women possess the same meaning as part of the duality of creation, and neither can be attributed a higher value.Whatever their orientation, all Koranic exegetes agree that the Koran establishes and defends the absolute justice of God as a divine attribute, which must be translated into the practice of justice in social and economic relations.

It is worth noting in this regard the hermeneutic of social justice that Amina makes of the Koran articulating the categories of ethnicity, social class, and gender.However, in practice, the principle of fairness is violated by granting absolute rights to men and relative rights to women. Amina Wadud notes such a violation in the different values that male commentators attribute to the male and female voice of God. They link the male voice to autonomy, hierarchy, domination, action, authority, control, and the female voice to nourishment, reciprocity, synthesis, and receptivity. In this case, divine justice is unfair and discriminatory to the detriment of women. To reverse this inequality, it is necessary to recognize the same value in both voices.

Iranian girl in the Nasir Al-Mulk Mosque in Shiraz. Photo: 123rf.com

Wadud notes with concern that in the collective imagination, both within and outside Islam, the static idea of a conservative Islam, which does not allow changes, is deeply rooted. To overcome this image, she believes it is necessary to distinguish between Muslim culture, Islamic texts, and Islamic law, and return to the Koran where the elements are found to break the static conception of the Muslim religion and its confinement in a rigid and immutable system.

And, it is from there that a gender-inclusive hermeneutic begins that discovers that women are moral subjects who maintain a direct relationship with God.

Her work Inside the Gender Jihad: Women’s Reform in Islam (Oneworld Publications, 2006) goes in this direction, where she proposes a Jihad (non-violent struggle) of women for justice and gender inclusion within the global Islamic community.

It addresses some of the major issues facing Muslim women today such as sexuality, leadership, education, and social status. What is proposed is to change the condition of women within Islam, a truly revolutionary task that Amina Wadud considers urgent.

This idea is developed and deepened in the tribute book dedicated to the study of her life and thinking on the occasion of her sixtieth birthday: A Jihad for Justice. Honouring the Work and Life of Amina Wadud, edited by Kacia Ali, Juliana Hammer and Laura Silvers (48HrBooks, 2012), which opens with the following text by Amina: “Listen to our song, and when the words are familiar, keep singing; for our people, silence has too often been what has sustained and nourished our principles”. (Open Photo: 123rf.com & CC BY-NC-ND 2.0/ Andrea Moroni)

Juan José Tamayo