Bartholomew, The Green Patriarch.

In his long-serving ministry, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew has unreservedly committed himself to the protection of the environment and the cause of peace, justice, and unity among all peoples, ceaselessly calling for effective solutions to the climate emergency.

There’s a proverb that says, “A society grows great when old men plant trees in whose shade they know they shall never sit”. The proverb certainly would be well understood by His Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, the 83-year-old spiritual leader of the world’s 300 million Orthodox Christians, known worldwide as The Green Patriarch.

In harmony with Pope Francis, whose Laudato Si’ document has become a road map for the ecological changes needed to conserve ‘Our Common Home’, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew said: “The world is not ours to use for our own convenience. It is God’s gift of love to us, and we must return His love by protecting it and all that is in it.” To be blunt, neither the Pope nor the Patriarch will live to see the benefits of the ecological campaigns they have initiated. Their faith tells them that we must act now to cut down emissions that will lead to the climate extremes that already affect livelihoods, food security, and peace itself.

“The world is not ours to use for our own convenience. It is God’s gift of love to us, and we must return His love by protecting it and all that is in it.” Photo: Ecumenical Patriarchate/Facebook

In May 2011, The Green Patriarch, wearing his ‘ecumenical’ hat, asked Churches to reflect on God’s love for the world, saying of weapons of mass destruction and of the climate crisis: “Our present situation is in at least two ways quite unprecedented. Never before has it been possible for one group of human beings to eradicate so many people simultaneously, nor has humanity been in a position to destroy so much of the planet environmentally. We are faced with radically new circumstances, which demand of us an equally radical commitment to peace.”This is a religious leader who is certainly no Johnny-come-lately to the issue of the climate crisis. He has been talking and writing about this crisis for a very long time, and has become internationally recognized for his vigorous leadership on environmental issues. Moreover, he has not confined himself to theological arguments but has raised the ethical aspects of the way the crisis must be addressed and offered practical solutions.

Tolerance From Asia Minor

Born on 29 February 1940 on the Aegean Island of Imvros, he was christened Demetrios by his parents, Christos and Meropi Archontonis.

He studied in Imvros and Istanbul, and then graduated with honours from the Theological School of Halki in 1961. He was ordained to the Holy Diaconate that same year at the Metropolitan Cathedral of Imvros and given the name Bartholomew. However, for the next two years, he was obliged to fulfill his military obligation in the Turkish army reserve.

He received his doctorate in Canon Law in 1968 from the Pontifical Oriental Institute of the Gregorian University in Rome before studying at the Ecumenical Institute in Bossey in Switzerland, and at the University of Munich, where he specialized in ecclesiastical law. Perhaps with this background, it isn’t surprising that Patriarch Bartholomew is fluent in Greek, English, Turkish, Italian, Latin, French, and German.

Patriarch Bartholomew. He has been able to nurture dialogue amongst Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. Photo: Ecumenical Patriarchate/Facebook

When he returned to Constantinople in 1968, he was appointed assistant dean of the Sacred Theological School of Halki and the following year was ordained to the Holy Priesthood. Six months later, he was elevated to the office of Archimandrite in the Patriarchal Chapel of Saint Andrew.

Under Ecumenical Patriarch Dimitrios, he was appointed director of the Patriarchal Office, and on Christmas Day 1973, Fr. Bartholomew was consecrated as bishop and named Metropolitan of Philadelphia in Asia Minor. He remained as head of the Personal Patriarchal Office until his enthronement as the Metropolitan of Chalcedon in 1990.

That same year, as Metropolitan Bartholomew, he accompanied Patriarch Dimitrios on a historic 27-day visit to the United States as his chief advisor and administrator.

Vocation To Ecumenism

During this steady career path, he had been a member of the World Council of Churches Faith and Order Commission, acting as vice president for eight years. In January 1991, Metropolitan Bartholomew led the Orthodox delegation at the Seventh General Assembly of the World Council of Churches in Canberra, Australia.

There, he framed Orthodox objections that the World Council was departing theologically from essential Orthodox beliefs – but that has not detracted from his strong advocacy for maintaining extended contacts with other Churches.

Pope Francis and Patriarch Bartholomew. (Photo Vatican Media)

These achievements meant that on the death of Patriarch Dimitrios on 2 October 1991, it was no surprise that Metropolitan Bartholomew was unanimously elected Archbishop of Constantinople, New Rome, and Ecumenical Patriarch. There followed what reads like a ceaseless round of visits abroad and meetings with religious and political world leaders. And perhaps because the Ecumenical Patriarchate has that very special geographical and spiritual position between East and West, Patriarch Bartholomew has been able to nurture dialogue amongst Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, and has extended the hand of spiritual friendship to the Far East, visiting China and Hong Kong.

A Peacebuilder

Patriarch Bartholomew has been a trailblazer in terms of interreligious dialogue. Contributing to reconciliation in the Balkans, addressing issues of terrorism, and negotiating in countries such as Iran by addressing their governments on subjects of concern – in 2002 he spoke to Iran’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs on “The contribution of religion to the establishment of peace in the contemporary world”.

Today, he and Pope Francis seem to be leading the world in their unremitting efforts to bring about effective solutions to the climate emergency. They sing from the same hymn book, with The Green Patriarch stressing that the ecological problem affects all humankind and above all has a painful impact on the poor and the weak.

Ukraine. Irpin. Damaged church and burned car as a result of the bombardment of the city of Irpin. 123rf.com

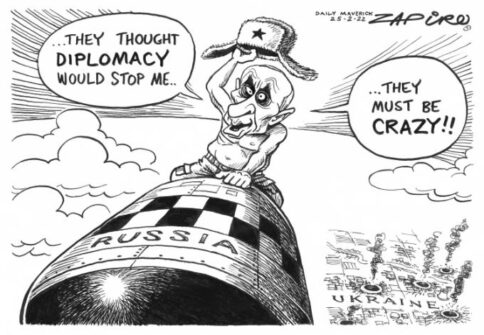

The Ecumenical Patriarch has also taken a strong position against the war in Ukraine. He said: “What is happening in Ukraine is a tragedy, it is a disgrace that will stigmatize forever those who caused it, those who turned out to have no fear of God.”

The Patriarch concluded: “ We stand and suffer alongside the pious and courageous people of Ukraine that bear a heavy cross. We pray and strive for peace and justice as well as for all those who are deprived of these. It is unimaginable for us Christians to remain silent before the obliteration of human dignity”. (Photo credits: sacredspace102.blogs)

Marian Pallister

Pax Christi

Scotland