UN. 2023. The International Year of Millet.

The cultivation and consumption of millet is a response to the challenges posed by population growth, food insecurity and climate change. A unique opportunity.

Among the first plants to be domesticated, millet is considered a cereal with a high content of nutrients. For seven thousand years, this small, round grain has been the staple food for hundreds of millions of people in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia and is now grown around the world. However, the production of this cereal species is declining in many countries and its potential to tackle climate change and food security is not being fully exploited, even though this herbaceous plant can grow on relatively poor soils and in arid conditions. Millet comprises a family of cereals produced from a variety of plants that have small seeds and are grown mainly on non-agricultural land, in arid locations, where irrigation may not be possible and access to markets is difficult.

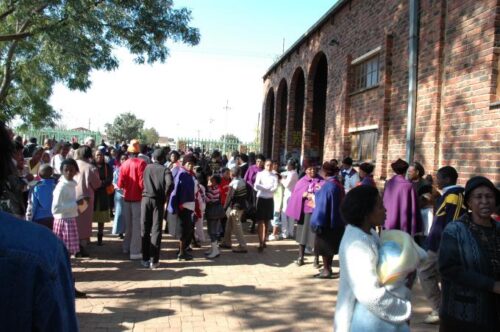

Photo: Fao/Simon Maina

Once critically endangered, the millet species is now recognized as part of the solution to global food problems, as it is an essential source of energy, and its crops can be stored or ground into flour.

Promoting the diversity and nutritional and ecological benefits of millet can benefit the food sector, from producers to consumers.

“For a long time, millet was considered a food for poor farmers, while urbanization and land mismanagement have led to the loss of farmland. With millet, degraded drylands can be reclaimed, making this cereal essential for feeding a growing world,” explains Jacqueline Hughes, director of ICRISAT, a crop research institute in the semi-arid tropics based in Hyderabad, Telangana, India. Currently, a surprisingly small number of plants are used for human nutrition, from which we receive most of the daily calories we need. Thousands of species and varieties of plants that fed our ancestors have become extinct.

Genetic diversity

Rapeseed is said to have been domesticated in northern China, and as the seeds were saved and passed down through generations of farmers, different types of rapeseed adapted to the ecosystems around villages: soils, climate, altitude and the availability of water. Cultural preferences also contributed to the seed selection process; some favourite plants were replanted for their specific taste, texture, or colour of the grains.

Now, after decades of neglect, millet is once again considered an essential food. At the suggestion of the Government of India and with the support of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed 2023 as the International Year of Millet, with the aim of increasing the contribution of these cereals to food and nutrition security, improving sustainable production and quality of cereals and increasing investment in research and development.

African women cooking traditional food. 123rf.com

The FAO defines millet as: “A unique opportunity to increase global production, ensure efficient processing and consumption, promote better use of crop rotation, and encourage better connectivity between food systems to promote millet as a key component of the food basket”.

Though vulnerable, indigenous and local communities around the world are major advocates for agrobiodiversity conservation, thanks to their traditional knowledge of different crop varieties and how to grow them. FAO’s International Fund for the Plant Treaty supports farmers in developing countries in their efforts to protect and use the genetic diversity of plants such as millet to ensure food security. “If millet replaced large areas of rice cultivation in India, scientific research suggests potential benefits, such as lower greenhouse gas emissions, greater resilience to climate change, and lower water and energy use, all without reducing calories or demanding more land”, summarizes journalist Dan Saladino, author of Eating to Extinction (2022, FSG), in Foreign Policy magazine.

Intelligent food

The United Nations encourages regions of Asia and Africa to replace the big three grasses (rice, wheat, and maize), which together provide more than 50% of human caloric intake, with millet. Over 90% of millet production today takes place in developing countries on both continents. From millet grains, bread, porridge, malt, and beer are made. As a ‘smart food,’ millet can significantly contribute to overcoming malnutrition, as its nutritional benefits can increase the growth of children and adolescents by 26-39% when substituted for rice in standard meals.

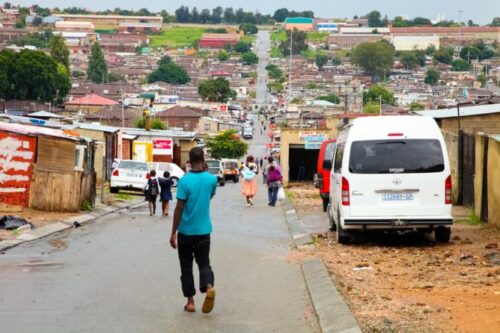

Fields of pearl millets in southeast Asia. 123rf.com

The study “Can feeding a millet-based diet improve the growth of children?”, published in the scientific journal MDPI Nutrients, points out that “nutritional intervention programs can be developed and adapted to increase the diversity of meals using millet and therefore improve nutritional content, including in school and mother-and-child feeding programs”.Research author R. Hemalatha, also director of India’s NIN Institute of Nutrition, suggests that “implementing millet meals requires designing menus for different age groups, using culturally sensitive and tasty recipes”. Millet also contributes to meeting the health needs of adults, helping to control diabetes, and overcome iron deficiency anaemia, as well as reduce cholesterol levels, obesity and the risk of cardiovascular disease. In Western countries, millet is sold in shops and in dietary sections and is mainly consumed in multigrain bread and used in the production of poultry feed. Thanks to the high fibre content and short cooking time, it can also be used in salads, purees, soups, or desserts. (Open Photo 123rf.com)

Carlos Reis