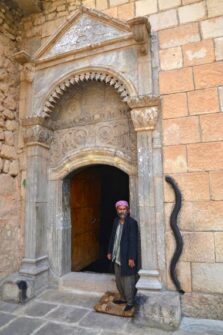

Iran. Young Generation: “We want to be free”.

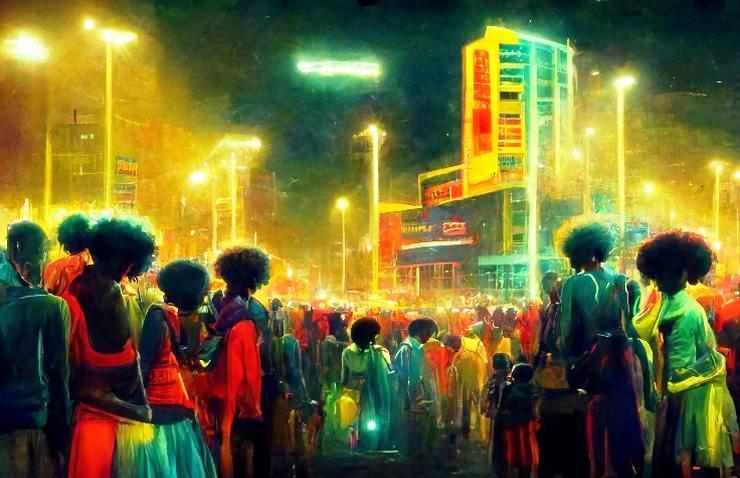

The current Iranian Revolution is entering its fourth month, with people all over Iran protesting. Iran’s Gen Z is leading the charge as the loudest voice of the protests not only in the streets but also

in the cybersphere.

Generation Z (Gen Z) are individuals roughly born between 1997 and 2012, a generation that is considered often “digital natives” due to the easier accessibility to digital technologies such as phones, the internet, and social media while growing up.

In Iran, the significance of Gen Z’s digital footprint, as well as their courage on the streets, is especially noticeable during the current revolution. It ignited after the killing of Jhina (Mahsa) Amini, a young 22-year-old Kurdish woman who died after being subject to violence by h Iran’s morality police because she was not wearing her headscarf according to Iran’s strict Islamic Laws.

Her death sparked protests and revolts all over the country, with mostly young people demanding a revolution and loudly chanting “Woman, Life, Freedom”. Over the past decade, the Iranian Gen Z has deviated from the regime’s official portrayal.

Since over 50% of the population is under the age of 30 and with over 80% of the population having access to the internet, Iran isn’t just a young country, but a digitally literate one as well. It’s no surprise that its Gen Z are experts on social media platforms like Instagram, Twitter and especially TikTok.

Contrary to its portrayal by state media and some Western outlets as equally conservative and religious as its political elite, Iranian Gen Zs succeeded in becoming a globalized and open-minded generation with great knowledge about the music, culture, and politics of states worldwide, including the US.

On TikTok, a social media app where one can record short videos, many Iranian Gen Z’s upload videos of themselves singing along HipHop songs of famous US-American artists or imitating scenes of US-American sitcoms such as “Friends”.

One tragic instance is that of Hadis Najafi, a young 23-year-old woman who was shot in the first weeks of the protests. Hadis had a TikTok account where she would frequently upload videos of herself dancing to popular Iranian as well as Western music.

Based on her online presence, one could have guessed that she was a young student living freely in California or London. In the last video that she posted on TikTok, she states, while heading to the protest, that in 10-20 years, when Iran will be free, she can say that she participated in the protests that enabled the revolution.

These videos, which are left as so-called digital footprints within the cyberspace, show how brave Iran’s young generation is. While the Iranian security forces use live ammunition, imprisonment, and torture as ways to intimidate protestors, it appears to only encourage young people further to take to the streets.

The freedom of speech many Iranian Gen Zs experienced their whole life solely within cyberspace is turning into demands for freedom in real life. An interview with a young Iranian girl from Mashhad reveals that before the revolution, many young people dreamed of leaving Iran to be able to have a better future.

This isn’t surprising since the unemployment rate amongst young people is at 40%. However, the current revolution appears to have changed the mentality of young Iranians. Now, many Gen Zs are convinced that the regime will change and that there is no point for leaving the country.

For instance, a video on TikTok of two young 17-year-old Iranian social media influencers in early November 2022 shows the significance of the current revolution. In the video, the two young boys say their goodbyes to their followers, stating that they will protest on the streets from now on, hoping to still be alive after the revolution and continue making videos. This hope for freedom has gotten stronger and has overcome the fear of the regime.

Indeed, after the revolution in 1979, Iran’s first Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini had announced that the next generations born into the Islamic Republic will grow to follow the strict and conservative laws and regulations based in the Shia interpretation of Sharia-Law.

The Iranian regime enforced this by creating strict gender divisions starting from primary schools, mandatory religion classes as well as the promotion of conservative gender roles. However, contrary to the hopes of Iran’s political and religious elite, the country’ young generation did not grow up to be conservative followers of the Iranian regime, instead creating spaces for themselves where they would meet in mixed-gender events such as underground concerts, listening to forbidden Western music and discussing contemporary global issues. Even one of Iran’s clerics stated in a Friday prayer in 2021 that the plan of the Iranian regime to raise a new generation of faithful followers, has failed.

A major factor for this lucky failure is Gen Z’s access to the internet. Sharing their own voices and listening to others freely within a digital reality impacted young Iranians more than the Iranian regime could have anticipated.

One of the current revolution’s youngest victims, Sarina Esmailzadeh, a young 16-year-old girl who was shot dead in the first month of the uprisings, had her own YouTube channel. In one of her videos a few months prior to her death, she stated that “All that we want is to be as free like young people in the US and in Europe, we want to live in stability and with a prospect for a good future, we want to be free”.

Sarina’s words summarize the major difference between the revolution in 1979 and the current one. In contrast to the revolution in 1979, the young people on the streets now have pragmatic hopes and dreams for their future. Whereas in 1979, the revolution was carried by Communist, Marxist, Student, and Islamist groups, all having their own ideology, Iran’s Gen Z appeases any type of ideology.

Their hopes and demands for Iran’s future are simple: financial and economic stability, gender equality, freedom for all ethnic minorities and social welfare. During several occasions, young Iranians have stated that they do not want to follow any ideology anymore since it has caused much division inside the country. All they demand is a freedom and just state for everyone.

As the revolution carries on, the international community should first and foremost listen to the demands of Iran’s Gen Z since their role within the revolution cannot be overlooked anymore. The Gen Z might be able to realize their digital freedoms in real life. At this stage, it is evident that Iran’s political and religious elite is not willing to listen to its young people demands, therefore the burden is on the international community to show solidarity with the young and brave people of Iran, who will continue chanting “Woman, Life, Freedom”. (Photo: CC BY 2.0/Matt Hrkac)

Arqavan Farsi/ISPI