Sixty Years Later. The Encyclical ‘Pacem in Terris’ Taught that War Is always Irrational.

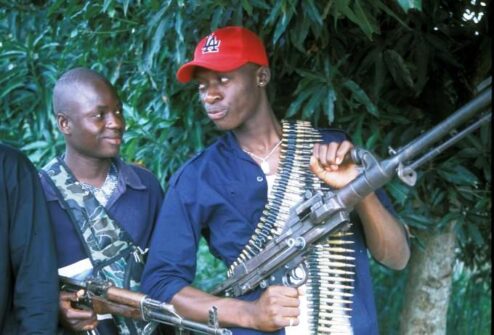

Today, the atomic threat is less feared, but the risk of an increasingly widespread and devastating conflict is real: from Europe to the Pacific, from the Middle East to Africa.

Sixty years ago, John XXIII’s encyclical ‘Pacem in Terris’ was published, arousing surprise and enthusiasm throughout the world. Everything about that encyclical seemed new and it was emphasized as the first pontifical document dedicated exclusively to peace and as the first that was addressed to all men of goodwill even if it was not so. There were, however, many innovations and one, in particular, was very important: the encyclical ruled out that, in the atomic age, war could bring justice. For some time now the Church had taught that war was evil, admitting it however as a legitimate defence and to restore a violated right. But John XXIII highlighted that the radically unbalanced relationship that had arisen between the means (nuclear weapon) and the end (restoring justice) now made it impossible to speak of a ‘just war’.

Pope John XXIII signs his encyclical “Peace on Earth” (“Pacem in Terris”) at the Vatican in 1963.

War had become an impracticable, counterproductive, irrational tool and, therefore, to be eliminated. It was what hundreds of millions, perhaps billions of men and women wanted to hear from such a high moral authority. Not only that: it was also what the top political leaders of the time, Kennedy and Khrushchev, wanted someone to say in order to deal more easily with internal resistance to an agreement with the ‘enemy’. It seemed as if the world was speaking with one voice, that of the Pope.

In ‘Pacem in Terris’, the novelty of the contents arose from a novelty of approach. That pontifical pronouncement was not based only on the Gospel and on Tradition but also on reading the signs of the times; that is, it was also based on the analysis of historical reality. This marked a detachment from a doctrine of the Church based on a theological and providential reading of history which, while judging war as an evil, considered it a punishment from God and therefore impossible to eliminate. With Pope John’s encyclical, the Church changed nothing of the evangelical message of which she is guardian and herald, but the encyclical has shown that even on the crucial themes of war and peace the Gospel is incarnated in ever new ways and resounds in forms unpublished in different historical contexts.

Today, war appears to many to be not only legitimate, but also useful and, in its own way, rational. It is rather peace that seems to have to be justified. When the first conflict after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Gulf War, broke out in 1991, it was said that ‘it would be the last’ or that it was ‘necessary to avoid more ruinous future wars’. At the time, there were people who rightly denounced the hypocrisy of such statements, but today, in some respects, there would be some reason to regret them: they implicitly recognized peace as a principle to be made prevail, even if they served to cover choices of just the opposite.

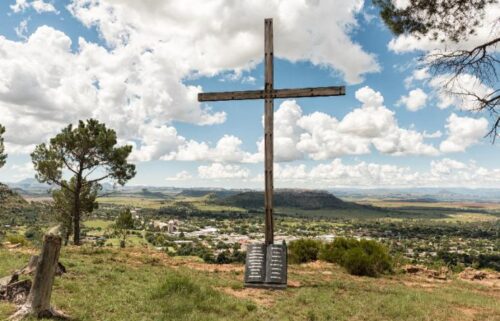

Photo: 123rf

Behind that hypocrisy, in fact, there were many important things: the memory of the two world wars, the continuity with an unprecedented system of international organizations to safeguard peace, the desire to avoid a Third World War at all costs. That war should be banned was still a widespread belief in 2003, when millions of people demonstrated around the world against the one in Iraq. Then something broke and war became ‘normal’. If today no one says that the war in Ukraine will be the last or that it is necessary to avoid others (and no one has said it even for those in Syria, Yemen, Georgia) it is because of the diminishment, after 1989, of the moral, political, institutional architecture built up after the Second World War.

Does this mean that the Gospel of peace no longer interprets the meaning of history? Quite the opposite: if the urgency for peace is no longer felt, it is because the signs of the times are no longer read and the history in which we are immersed is not questioned in depth. John XXIII’s lesson is more timely than ever as war rages in Ukraine and in other parts of the world. Even today, there is a Pope who insistently proclaims the Gospel of peace, in full continuity with the spirit of Pope John. But questioning the history of our time is not only the Pope’s responsibility. Supporters of peace should not only underline (rightly) its urgency, but also contribute to building a solid culture of peace interwoven with historical knowledge.

Photo: 123rf

The culture of the time in which ‘Pacem in Terris’ was written was able to combine eschatological hope and historical realism and show convincingly that war was no longer reasonably usable.

A similar effort is also needed today. Those who believe in peace cannot ignore the task of exploring – together with all ‘men of good will’ – the rational, concrete, compelling reasons, i.e, the historical reasons, why it is urgent to end the wars in Ukraine and elsewhere. Obviously, the millions of refugees from Ukraine – the relatives of the victims of Russian aggression, those who live daily under bombs – do not find it difficult to read the signs of the times.

But if those who suffer from war grasp more than others that the future of humanity passes along the road to peace, this must also be understood by those who live far from war and, above all, by the ruling classes of many countries which, directly or indirectly, can contribute to peace. In short, even by the Kennedys and Khrushchevs of today and, above all, by their more modest followers.

While the atomic threat is no longer as frightening as it was sixty years ago – though the danger of nuclear weapons has far from disappeared – the risk of an increasingly widespread and devastating conflict is dramatically real, from Europe to the Pacific, from the Middle East to Africa. Many do not understand that war always produces unpredictable outcomes, despite the fact that this has been clearly seen in Iraq, Afghanistan and many other places. But it is in everyone’s interest to prevent the world from plunging towards catastrophic outcomes and a culture is needed that clearly highlights the many reasons – human, political, economic – for this interest that is capable of revealing the irrationality of indifference. Undoubtedly, the prevalence of a single thought that today imprisons peoples and the elite, based on immediate interests, on the threat of violence, on the logic of bipolar opposition is only one of the causes of the increasingly frequent recourse to war. But it is a cause that reflects all others and a different culture is essential to find that peace which today is hard even to imagine.(Photo: 123rf)

Agostino Giovagnoli

Catholic University of Milan