Tshisekedi’s businesses.

Widespread corruption, disorganised armed forces, and a system of power based on patronage networks. The portrait of a head of state who, betraying the ideals of his party, is favouring his own community, aggravating ethnic tensions.

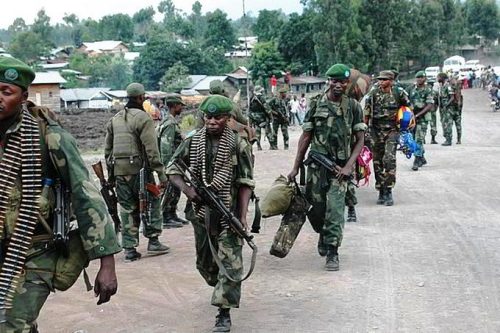

Since late 2021, the Democratic Republic of Congo has been the scene of growing instability, fuelled by the advance of the M23 rebel movement, led by ethnic Tutsis. In December 2023, this group was strengthened with the integration of the political wing, Alliance of the Congo River (AFC). The conflict between the M23, supported by the Rwandan army, and the government forces of Kinshasa, disorganised and supported by numerous local armed groups, intensified in early 2025 with the occupation of two important eastern cities, Goma and Bukavu.

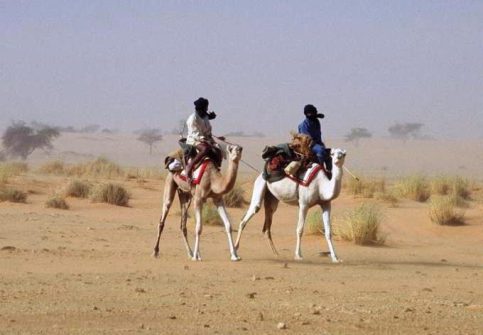

M23 fighters moving along the road towards Goma. The initial objectives of the M23 were relatively simple to address. © Monusco/Sylvain Liechti

This military escalation is a gamble. Western countries, which had previously ignored the international violations committed by Rwanda, have now imposed sanctions, contributing to a change in the global perception of Rwandan President Paul Kagame. An authoritarian but development-oriented leader, Kagame is now seen as a ruthless dictator, intent on redrawing the borders between Rwanda and the DRC. However, this international condemnation should not obscure the responsibility of Congolese President, Félix Tshisekedi, in the current crisis.

The initial objectives of the M23 were relatively simple to address. But the agreements signed with its factions were ignored by the Congolese presidency, which refused any negotiation, branding the rebels as “terrorists”. This hard line has allowed Kagame and the M23/AFC coalition to expand their territorial control, raising the bar of ambition to the point of aiming for the removal of Tshisekedi from Kinshasa.

Money vanished into thin air

Compared to the rebels, the government army appears disorganised and poorly paid, despite having been allocated $3.8 billion for defence since the beginning of the conflict. An intelligence document reports embezzlement of $722 million, suggesting that for many senior officers and politicians, the war is above all an opportunity to enrich themselves. Significant bribes reportedly accompanied the purchasing of weapons.

In an attempt to strengthen the armed forces, many local armed groups were formally integrated as reserves, but with poor training and poor management contributing to a climate of persistent insecurity.

The Congolese National Armed Forces (FARDC). The government army appears disorganised and poorly paid, despite having allocated $3.8 billion for defence since the beginning of the conflict. © Monusco/Clara Padovan

This approach reflects the regime’s style of governance. When Tshisekedi was proclaimed president in 2019, despite the victory actually being that of Martin Fayulu, there were expectations of improvement, thanks also to the history of his party, the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS). This party had historically fought against dictatorial regimes such as those of Mobutu Sese Seko and Laurent-Désiré Kabila and was committed to the rule of law.

Unfortunately, the current government has proven worse than the previous one, betraying the founding ideals of the UDPS, partly due to Tshisekedi’s inexperience and incompetence.

Progress has been limited. Political opponents and dissidents are routinely arrested on treason charges and detained illegally. Corruption is rampant, not just tolerated but almost legitimised. The president himself has publicly declared bribes a legal practice, defending the finance minister accused of embezzling millions of dollars, calling him “probably the best finance minister in the history of the country.” The general inspectorate of finance, while investigating numerous cases, rarely sees its reports translated into prosecution.

The ruling party is now in deep crisis. In the 1990s, it was the main opposition force and attracted prestigious intellectuals. Today, it is emptied of its most competent figures, led by a controversial secretary general completely subservient to the presidency and composed mainly of unemployed youths recruited as militants. Some of these informal movements have transformed into militias that operate above the law.

Family Affairs

The situation is particularly critical in the four provinces of former Katanga, the homeland of former President Joseph Kabila and a mining region that is key to national finances. Local sources and civil society reports document how members of the presidential family control and exploit artisanal mineral deposits with the support of the presidential guard or the army, violating regulations even on industrial sites. Some reports denounce actual raids on foreign mining companies, forced to work one week a month for the presidency.

In Lubumbashi, the building of the General Management of Gécamines. The state-owned mining company Gécamines suffers from liquidity problems due to frequent withdrawals by people close to power. (Courtesy of Gécamines)

The state-owned mining company Gécamines suffers from liquidity problems due to frequent withdrawals by people close to power. Influential figures in the presidential family and party have created networks of clientelism that reach down to the lowest levels of the political and military structures. These competing networks neutralise each other, making it almost impossible to remove officials protected by higher levels and paralysing the system. Tshisekedi’s regime enjoys solid support in the Kasai region, his homeland, especially among the Luba ethnic group, who consider themselves legitimized in power after years of fighting against dictatorship and discrimination. The cohesion of this community is remarkable. However, the numerous appointments of people from Kasai in the administration and state companies have created the impression of a government that favours a single community, contrary to the tradition of previous Congolese presidents of maintaining regional balances.

Clashes between communities

This is particularly sensitive in Katanga, where social competition between Katangese and natives of Kasai has always been conflictual. The situation has worsened under Tshisekedi, due to the massive immigration from Kasai to Katanga. The “immigrants” engage in small-scale trade, motorbike transport and menial jobs, becoming very visible in Katangese society. Their different traditions, their backward social status and a triumphalist attitude, based on the predominant role in government, fuel tensions and conflicts.

Former President Joseph Kabila has allied himself with the rebel movement. M23/AFC. (Facebook)

Many feel untouchable, protected by members of their community at government and presidential levels. At the important border of Kasumbalesa, where most minerals and goods pass through, the UDPS militias have established a parallel control system to collect informal “export taxes”. This situation fuels the perception among Katangese of being dominated by a regime that favours a single community. As former President Kabila, originally from Katanga, has allied himself with the rebel movement M23/AFC, many Katangans hope that he will end Tshisekedi’s regime, unaware that the military movement is an instrument of Kagame’s power politics.

In the occupied territories, the M23/AFC rules by repression. In the west of the country, Tshisekedi’s tough stance against Rwanda is appreciated, but not his system of power. Unfortunately, neither Tshisekedi nor Kabila represent a hope for better governance. Kabila seems to want to take over from where he left off in 2018, when he was rejected for his attempts to stay in power. His possible return is not welcomed in many areas, due to his explicit alliance with the M23/AFC and its supporters. In 2024, Tshisekedi attempted to amend the Constitution to stay in power indefinitely. If he were to retain control, he would likely try again to protect his community and his family’s access to financial resources. In either case, they would rule against the will of a significant portion of the population, resorting to repression.

People trust the Churches

In this scenario, the Catholic and Protestant Churches, among the few institutions left with legitimacy and moral authority, are trying to unite civil society and other stakeholders to propose concrete solutions to the country’s real problems through a national consultation.

This may be the only way to build a better future, but it requires significant regional and international support. It is a fundamental step to avoid the mistakes of the past.

Cardinal Fridolin Ambongo Besungu, Archbishop of Kinshasa. The Catholic and Protestant Churches, among the few institutions left with legitimacy and moral authority. Photo: José Luis Silván Sen

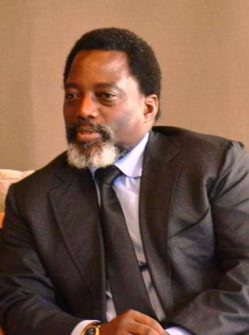

Too many times, in fact, tensions in Congo have ended with peace agreements between elites, capable of temporarily calming violence and insecurity, without, however, addressing the root causes that have afflicted the country for decades, especially in the east. There, the absence of effective state authority has given way to the domination of armed groups that protect the illegal exploitation of mineral resources. There are also networks of mineral smuggling to Rwanda and Uganda, complex land ownership issues, difficulties in the return of refugees and the need for reconciliation between Rwandan and other communities. These unresolved issues continue to undermine national stability, making it indispensable a new and concrete approach which goes beyond window-dressing agreements. Now is the time to seek real solutions, a complex but unavoidable challenge. (Open Photo: Democratic Republic of Congo’s President Felix Tshisekedi. Shutterstock/Alexandros Michailidis)

Erik Kennes