Africa. More Drinking Water from the Sea.

North African countries, in particular, are trying to cope with water shortages with new desalination plants. However, they risk having a serious impact on marine ecosystems and fishing activities.

The worsening water emergency is one of the most problematic effects of climate change that the countries of North Africa are dealing with. Since 2018, Morocco has been suffering from a situation of ‘structural water stress’, as denounced in July 2022 by the World Bank.

Last year in the country, the total volume of rainfall did not exceed 17 billion cubic meters, the lowest in the last five years.

A collapse that is leaving the approximately one hundred large active dams dry, which today contain barely 4 billion cubic meters of water, with a filling level stopped at 24%.

To curb this emergency, the government is betting on the construction of new seawater desalination stations. There are currently nine operational in Morocco.

The first to be built was that of Boujdour, in Western Sahara, in 1977. These plants cover no more than 3% of the national production of drinking water, a percentage that the government intends to shoot up to 50% in a few years.

The spotlight is on the Casablanca station. Announced as the largest in the entire African continent, once fully operational this month of June, this plant will have a capacity of 300 million cubic meters per year and will guarantee the supply of drinking water to almost 7 million Moroccans living in the territories of the former region of Grande Casablanca and in the neighbouring areas of El Jaida, Azemmour, Settat and Berrechid.The Dakhla station (Western Sahara), whose capacity is 90,000 cubic meters per day, should instead come into operation from 2025. Its construction was entrusted in 2019 to the Moroccan company Nareva, a subsidiary of the holding company of King Mohammed VI Al Mada, in partnership with the French Engie. Two more plants are planned in Safi (central-western part of the country, with a capacity of 30 million cubic meters per year) and in the eastern part (initial capacity of 100 million cubic meters).

Investments

Algeria has been suffering from water shortages since the 1990s. In the country there are fourteen active desalination stations between Algiers, Oran, Skikda, Tlemcen, Boumerdès, Tipaza, Mostaganem, Ain Temouchent and Chlef, which together produce over 2.7 million cubic meters per day. The government’s goal is to reach 2030 with 25 stations. For this year, the works for the construction of 13 new plants are ready to start. The construction of another 5 was entrusted last May by the government to the Algerian Energy Company.

Rocky and sandy shores of Dakhla. CC BY 2.0/ Ecemaml

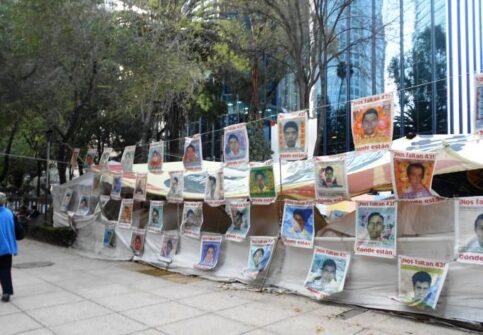

In Tunisia, whose major plants are located between Djerba (50,000 cubic meters per day), Skhira (12,000) and Gabès (30,000, where brackish water is desalinated), a new station is under construction in the southern part of the country. The works, led by the British Solar Water PLC, require an investment of 567 million euros for an expected capacity of 200,000 cubic meters.In Egypt, whose water supply depends to a large extent on the waters of the Nile River, in early December Ayman Soliman, managing director of the Egyptian sovereign wealth fund, announced an impressive program which envisages the construction of 21 desalination stations. When fully operational from 2025, they will produce 3.3 million cubic meters per year. The allocated budget is 3 billion dollars.

Environmental alarm

In West Africa, the country that is investing the most in this direction is Senegal, where work is continuing on a plant located on the Les Mamelles heights in the town of Ouakam. The station, the first of its type in the whole region, will have a capacity of 50,000 cubic meters per day (expandable up to 100,000) and was designed to improve the supply of drinking water in Dakar, whose supplies depend heavily on Lake Guiers, located 250 km north of the capital. Several local associations that fight for the defence of the coasts fear the environmental impact of the work. With the reverse osmosis technique, the water, passing through osmotic membranes due to the effect of a higher pressure, is freed from all unwanted substances and thus purified.

African girl drinking clean water from a tap. Photo 123rf

In this way, an average litre of drinking water is obtained from two litres of salt water, with the remaining litre of brine being discharged into the sea with damage to the marine ecosystem and, consequently, to the activity of the fishermen. These fears were expressed in 2019 by the United Nations which raised the alarm about the harmful effects that massive discharges of brine into the sea cause, on marine ecosystems.

On a planet increasingly dry of blue gold, stopping the spread of seawater desalination plants, however, appears increasingly complicated. There are currently 15,000 in operation in 177 countries, most of which are concentrated in the Middle East. With the costs of producing drinking water continuously falling, and the cubic meter expected to drop to 0.15 euros in 2025, their construction is set to expand – in North Africa and also below the Sahara. (Open Photo: 123rf)

Rocco Bellantone