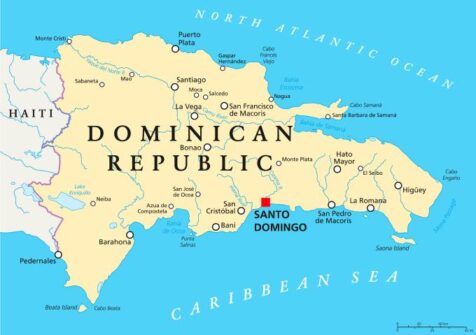

Dominican Republic. The Gateway to North and South America.

A painful story that continues today. Internal tensions have favoured the spread of corruption. Difficult union with Haiti. Privileged relationship with the United States. Increasing tourism.

The Dominican Republic is located on Hispaniola Island which it shares with Haiti, which borders it to the west. It occupies about two-thirds of the entire territory of the eastern side which corresponds to an area of 48,671 km². The country is bordered to the north by the Atlantic Ocean, to the south by the Caribbean Sea, and to the east by the Mona Passage which separates it from Puerto Rico.

The territory is mainly mountainous, with a series of successive chains from west to east. In particular, in the Cordillera Central, there are peaks that reach considerable heights and among these, the Pico Duarte stands at 3,098 m. representing the highest point not only of the country but of all the Caribbean islands.

123rf.com

The hydrographic network is quite developed and is characterized by five main basins of which the Rio Yaque del Norte, which flows for 296 km, is the longest and most important river in the Dominican Republic. There are also several lake basins scattered throughout the territory, but generally small in size with the exception of the saline Lake Enriquillo, whose surface area of 265 km² makes it the largest in the Caribbean.

The history of the island, as with most of the countries in the area, has been strongly conditioned by the effects of colonization and this can already be seen from the name that was assigned to it in 1492 upon the arrival of Christopher Columbus.

Santo Domingo. The Christopher Columbus Monument.

Since then, Hispaniola assumed a high strategic value by serving as a logistic base to be used for penetration into the southern region of the American continent. This resulted in the extermination of the aboriginal population, the Taina, in less than 25 years, and the occupation of the territory rich in gold mines and arable land in which a growing number of African slaves imported massively by the Spaniards was employed in the first twenty years of the 1500s.

In 1520, the Spaniards lost interest in the island leaving it in the hands of a local governor to head towards new lands. This facilitated the penetration of English, French and Dutch explorers into the western area which corresponds to present-day Haiti. Among these, the French had the upper hand and after having officially obtained a third of the territory from the Spanish crown calling it Isle de Saint Domingue, they converted the area to sugar production, transforming it into one of the richest colonies in the world and the most lucrative in the Caribbean, obviously backed by a cruel system of slavery.

The rivalry between Haiti and the Dominican Republic

At the beginning of the 1800s, the echoes of the French Revolution reached the Caribbean Island, generating insurrections among the population after years of terrible mistreatment. This resulted in the declaration of war against the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte which, in 1804, gave rise to the independence of Saint Domingue which was renamed ‘Haiti’, i.e., land of high mountains, going down in history as the first independent nation in Latin America and the oldest

Black republic in the world.

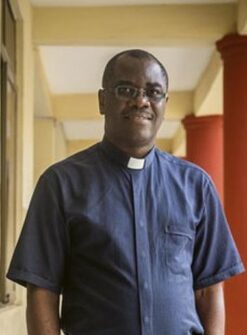

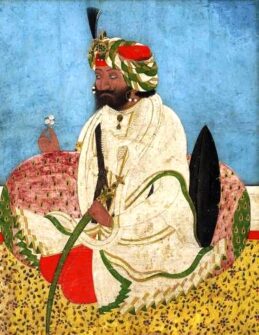

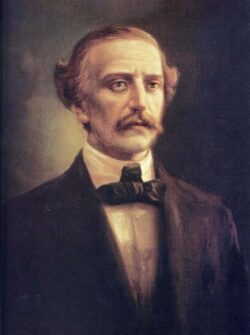

Juan Pablo Duarte, founder of the Dominican Republic. Oil portrait of Duarte by Dominican artist Abelardo Rodríguez Urdaneta.

All this was won at a very high price as Haiti was obliged by the French until 1947 to pay a gigantic indemnity to compensate for the money, they would not have received due to the lack of exploitation of the territory.

The eastern part of the island that remained under Spanish rule declared itself independent in 1821 under the name of ‘Spanish’ Haiti. This condition, however, lasted just two months since in 1822 it suffered the occupation of neighbouring French Haiti, which lasted for more than two decades, giving rise to countless social conflicts that are still present today. In fact, Haiti governed with the aim of unifying the island and to do so it adopted drastic repressive measures such as the prohibition of the use of Spanish in official documents, the introduction of French in primary education, and the limitation of Spanish cultural traditions. In addition, the French government enacted land reform that harmed white landowners and forced Dominicans to contribute to the payment of the huge Haitian debt. From the Dominican perspective, these actions were seen as a forced ‘Haitianization’ which resulted in the birth of a secret separatist group which succeeded in declaring independence in 1844. It was only then that the eastern part of the island began to call itself the Dominican Republic which, however, in the 20th century underwent a new occupation by the United States.

At the Border of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. CC BY 2.0/Alex Proimos

These historical processes led to very strong social inequality between the two parts of the island that identify themselves as two distinct peoples. In the genesis of the two states, we can thus grasp the reasons for the rivalry, not yet completely dormant, which has characterized the relations between Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

The Haitian occupation and the clashes that took place in the following decades have, in fact, compromised relations between the two countries; the rivalry has been renewed and exacerbated several times in the course of recent history, also in conjunction with the increase in illegal migratory flows of the Haitian population towards Dominican territory. Furthermore, the subsequent economic imbalance between the two countries achieved over the years has led many Haitians to cross the border. For many generations, in fact, Haitian farmers have been key elements in the development of the Dominican economy as a low-cost labour force. This phenomenon is still very much felt today and constitutes a real problem for the country. In fact, considerable flows of migrants depart from Haiti to cross the borders illegally to find work in the fields of sugar, coffee, and tobacco, generating a situation of difficult coexistence. In February 2022, the President of the Dominican Republic Luis Abinader announced and commenced the construction of a 164 km barrier along the border with Haiti, aimed at stopping illegal immigration and drug trafficking. (Photo: 123rf.com) – F.R.