South Africa. Catholic bishops back miners’ compensation claims for black lung disease.

Last August, Southern African bishops filed a class-action suit against a mining company that has failed to compensate miners for black lung disease. This is one of the many cases in an industry where workers pay a huge tribute to profits.

South Africa’s mining sector contributed in 2022 US $ 25 billion and 8 percent of the national GDP. Yet, the miners whom the country owes such amount of wealth get little recognition as some large corporations fail to compensate them for occupational diseases.

On 15 August, the Southern African Catholic Bishops’ Conference (SACBC), which groups of bishops from Botswana, South Africa and Eswatini, filed a class action lawsuit with South Africa’s High Court Gauteng Local Division, against a subsidiary of the Australian mining major BHP, South32 and against the South African Energy company Seriti on behalf of 17 current and former miners.

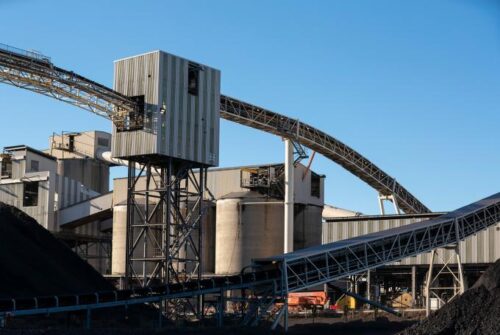

Illawarra Metallurgical Coal. South32 has three mining operations in South Africa (Photo: South32)

The workers had previously called the Catholic Church for help after contracting incurable coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, also known as black lung disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease causing breathing difficulties, airflow limitations, and constant chest pains.

In an application for certification of a class action, the Conference’s Commission for Justice and Peace accused the coal mining company South32 of failing to provide workers with adequate training, equipment and a safe working environment, as required by law. According to the application, both diseases caused by coal mine dust can be prevented. The Commission asked the court to order compensation to be paid to those workers. The plaintiffs also call for compensation for the coal miners who died from these diseases.

Cardinal Stephen Brislin, Archbishop of Cape Town.

Cardinal Stephen Brislin, the archbishop of Cape Town, justified in a statement the bishops’ initiative because some of the plaintiffs are retired workers who do not receive any more legal assistance from the trade unions of which they were members when they were still working in the mines. The bishops’ initiative is inspired by the Catholic social teachings included in Pope Leo XIII’s 1891 encyclical on capital and labor, “Rerum Novarum”. The claim that “the Church has been close to the suffering of unskilled and vulnerable workers in the context of unbridled industrialization and its support for the coal mine workers is a concrete manifestation of its defense of the dignity of work which is a function of God’s creation”, say the bishops.South32 which is a multibillion-dollar metal mining company based in Perth (Australia), operated South Africa Energy Coal from 2015 to 2021 and has still three operations in Southern Africa (South Africa Manganese and Hillside Aluminium in South Africa and Mozal Aluminium in Mozambique). One of its spokespeople answered to press queries after the SACBC filed its suit, that the company was “unable to comment further at this point in time.”

South32 which has three mining operations in South Africa and employs 9,100 people worldwide, has already run into other disputes this year. In July 2023, it was ordered to pay $2.9m in compensation after an investigation found that one of its coal mines in New South Wales (Australia) had been draining local drinking water to its facility over the last five years. The mine’s operator Illawarra Coal Holdings, a subsidiary of South32, admitted that it never had the permit to use any surface water supply for its mining activities.

In addition, at the end of August, the Australian Collieries’ Staff and Officials Association (CSOA) said that workers at South32’s Appin mine had failed to reach an agreement with the company over an industrial dispute over “having a reasonable work/life balance”.

Hillside Aluminium. South32 employs 9,100 people worldwide. (South32)

Yet, South32 is far from being the only company accused by its own workers of violating their basic rights. In March, the Director of the Commission for Justice and Peace of the Southern African Catholic Bishops’ Conference (SACBC), Dominican Father Stan Muyebe, urged two gold mining companies, DRDGOLD and East Rand Properties Mines (ERPM) to “settle their historic debts to mine workers made sick in their mines as a result of working in unsafe conditions”.

According to Father Muyebe, while 19 companies accepted to settle damages and compensate miners after a class action suit was approved by the High Court in 2019, DRDGOLD and ERPM have appealed the ruling and do not seem to have the intention to pay such compensations for miners who suffer from silicosis and tuberculosis caused by exposure to high levels of silica dust while working in the gold mines or for the families of those who died.

The issue is an important one. In 2022, more than 475,000 workers were employed in South Africa’s mining industry, facing many health challenges. Professor Jill Murray of La Trobe University School of Law in Melbourne and specialist in international labour relations reported that South African miners were facing an epidemic of occupational lung diseases such as silicosis and tuberculosis and that initiatives to influence policy and thus reduce dust levels and diseases had been largely unsuccessful. Obviously, the cases raised by the Commission for Justice and Peace Commission show that the issue remains unsolved.

South African miners. 123rf.com

Another study published by the executive director of the National Institute for Occupational Health in Johannesburg, Barry Kitansamy and other researchers in 2018, revealed that between 2012 and 2017, 111,000 miners received compensations, half of them for permanent lung impairment and 52,000 for tuberculosis. Yet, accordingly, an almost equivalent number of claims (107,000) were unpaid.

Dr Gill Nelson, an epidemiologist from the Faculty of Health Sciences at Witwatersrand University also found out that between 1975 and 2007, the percentage of white miners with silicosis increased from 18% to 22% in gold mines while the proportion of black miners affected with the same disease soared from 3% to 32% in the same environment. The study concluded to the failure of the goldmines to control dust and prevent occupational respiratory diseases in the workplace. Besides, Dr Nelson identified high risks of asbestos-related diseases in diamond and platinum mines. (Photo:123rf.com)

François Misser