United States-Pakistan: obstacles to relaunching relations.

In September, the United States undertook a series of initiatives

aimed at reviving its complex relationship with the Islamic

Republic of Pakistan.

The latter, in fact, has not appeared among the priorities of the American Administration for some time, which does not mention Pakistan in any of the latest strategic documents produced, including the strategy for the Indo-Pacific and the national security strategy.

In this context, on September 7, Islamabad’s Trade Minister Gohar Ejaz met with American Ambassador Donald Blome to discuss the state of economic and trade relations between the two countries.

Although the United States is actually Pakistan’s main export market and stands out among the top investors in the country, trade and investments are relatively stagnant.

The meeting between the Pakistani minister and the American ambassador focused on the possibilities offered by the “Special Investment Facilitation Council,” the hybrid civil-military body established by the Pakistani government in June to attract

direct foreign investments.

The discussions, concerned in particular, the strengthening of trade in sectors such as textiles and food products, while strategic areas such as energy, information technologies and minerals received less attention, largely dominated at this stage by the countries of the Gulf.

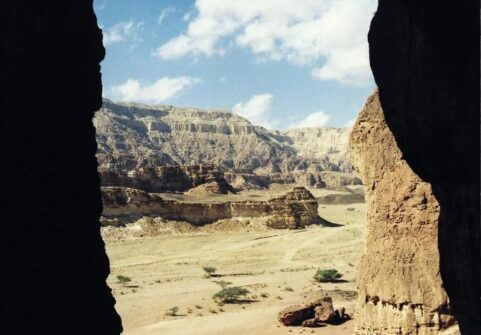

More recent is the visit of US Ambassador Donald Blome on 12 September to the port of Gwadar, a fundamental hub of the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). During the meeting at the Pakistani port, located in the unstable province of Balochistan, Blome underlined the potential and strategic value of Gwadar as an intermediate regional hub to which products destined for the Pakistani market and beyond can be transported. This move appears to be a signal addressed to both the Pakistani and Chinese authorities regarding Washington’s desire to prove itself present and attentive to regional dynamics.

However, the most recent meetings must be inserted not only in a broader framework of economic and commercial initiatives but also in the policies being followed between the USA and Pakistan. For example, in February 2023, a US delegation travelled to the country for what was the ninth meeting under the Trade and Investment Framework. Previously, on 23 September 2022, there was a brief summit meeting between the then Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and the President of the United States Joe Biden, in which the former underlined the importance of continued collaboration between the two countries.

However, these attempts at rapprochement must deal with a series of factors that render their success complicated.

At this stage, two above all, seem to slow down this process: the American focus on the strategic partnership with India and, above all, the role of China as a fundamental partner from an economic, political and strategic point of view of Pakistan.

In the Sino-Pakistani vision, in fact, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor would allow the latter to take advantage of Chinese production capacity, capital and know-how for an improvement in infrastructure as a useful element in resolving the structural economic-social instability. Beijing, on the other hand, is focusing on Pakistan to build alternative trade routes to the Strait of Malacca and, as has happened historically, to balance its Indian rival in South Asia.

Pakistan’s relevance for China emerges from the number of projects launched in the country, some of which are linked to the BRI, with the energy sector emerging as a priority. Among these, we may mention the Diamer Basha dam worth 8.8 billion dollars on which the joint venture between Power China and the Frontier Works Organization, controlled by the Pakistani army, is working.

But China is also active in the country’s automotive sector, with the Chinese Changan Automobile Company setting up a $136 million assembly plant in Karachi together with the Master Group of Industries. The strong ties between Beijing and Islamabad are also evident when looking at partnerships in the defence sector and the share of Pakistani foreign debt held by the Chinese.

In 2022, the latter amounted to approximately 127 billion dollars, of which around 27 were held by China. Through the Chinese State Exchange Administration, Beijing has deposited a total of around 4 billion dollars in the central bank of Pakistan in order to support the country in an economically difficult phase.

In this context, Washington’s efforts do not seem to be able to produce the desired results and, consequently, a US-Pakistan rapprochement appears unlikely in the short term. (Photo: The port of Gwadar.123rf.com)

Alessia Ferraboli/CgP