African Startup, an Expanding Universe.

The projects of young technological entrepreneurs in healthcare, agriculture, the environment, logistics, finance and e-commerce

are multiplying.

Agile, young, innovative. And certainly full of vitality. This is the startup sector in Africa. In recent years, ideas applied to technology – by Africans to solve African problems and needs – have multiplied.

So much so that we are now talking about African Silicon Valley(s). Hundreds of hubs developed especially in Rwanda, Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, Egypt, and Morocco.

Six startups were nominated for the World Economic Forum’s Technology Pioneer Lists last year, with branches ranging from healthcare to financial and insurance services to e-commerce.

It is, therefore, an expanding sector, not only from the point of view of creativity but also – obviously – from that of investments.

Venture capital investments, as reported by Forbes, should have reached 7 billion dollars this year.

Yet, according to the latest data, in the first quarter of 2023, African startups raised 57.2% less capital than last year. In 2022, the total investment raised was $6.5 billion.

Six startups were nominated for the World Economic Forum’s Technology Pioneer Lists last year. 123rf

In any event, the energy of young entrepreneurs continues to expand, and if until about seven years ago, Africa did not have unicorn startups, i.e., those valued at over a billion dollars, by 2021 the continent was already home to seven of this type.

Google for Startups (GfS) recently announced new funds, announcing the 25 new African companies selected for the Black Founders Fund. A fund that this year reaches 4 million dollars.

It is a financing mechanism – now in its third year – which in the intentions of the US giant aims to overcome what has been defined as ‘Racial and systemic inequality in the financing of venture capital (VC)’. Of the startups selected, 72% are led or co-founded by women.

The sectors in which selected companies operate include a technology platform for mental health services, an artificial intelligence-based mobile technology to improve agriculture, banking, healthcare and insurance, logistics and transportation, retail, and a fintech that aims to become Africa’s first women-focused bank.

However, a sensitive question concerning startups is whether they will last and for how long; in short, their sustainability over time. In 2020 the failure rate ranged from 58.7% in Kenya to 75% in Ethiopia.The main reason (not only in Africa but globally) lies in the depletion of funds and, immediately following, in the lack of a market for products or services.It is therefore obvious that the initial evaluation – by innovators as well as by lenders – requires much more than a good idea and enthusiasm.

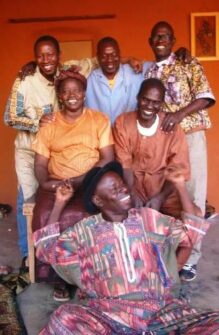

African Startup. Agile, young, innovative. And certainly, full of vitality. 123rf

The interesting thing, however, is that the report from which those data were extracted, The Better Africa, states that – from 2010 to 2018 – the startup closure rate for Africa in total was 54.20%., a much lower result than countries such as the United States, China, and India. While in 2022 in the MENA area (Middle East and North Africa) there was an increase of 24%.It is interesting to know this new generation of young entrepreneurs, born like their Western peers with a natural approach to technology and its means.

Starting from the lockdown period, the US broadcaster Voice Of Africa (VOA) has opened a series – obligatory title, StartUP Africa – in co-production with the main television stations in Nigeria, Ghana, Rwanda, Uganda, and Kenya, which tells the stories of the challenges, hopes and fears faced by young tech entrepreneurs across the continent.

The series includes how to turn ‘simple’ ideas into profitable businesses. It’s also a way to learn about the phases of their work, the ability to participate in business incubators, to network and exchange ideas within and outside their respective areas. And, not to be underestimated, it showcases a way to inspire and encourage other young talents. (Open Photo: 123rf)

Antonella Sinopoli