Three young Comboni Missionaries from different countries speak about their vocation and missionary experience.

My name is Lwanga Kakule Silusawa a Comboni missionary brother working in our missionary magazine Afriquespoir in Kinshasa, DR Congo. I was born in Butembo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, in a Catholic family. In 2009, I joined the postulancy in Kisangani where I continued to discern my vocation after which I was admitted into the novitiate. I did two years of novitiate in Benin and Togo. Thereafter, three years of theological studies in Colombia.

In 2014, I started studying journalism in Madrid, Spain. A year later, I joined the editorial team of the monthly Comboni magazine Mundo Negro. I worked there for four years. I corrected texts sent to me by missionaries from all over the world, specifically from Africa and Latin America, and presented them to the editor for publication.

Combining theory received in college with the practice of writing for the magazine was a luxury that none of my college classmates had.

Six years later, I came back to my land. I arrived in Kinshasa, on 15th January 2020, shortly before the Covid pandemic. The editorial team of Afriquespoir was waiting for me. I took a few weeks to know the reality and to immerse myself in the editorial line of this quarterly magazine.

Here, it is no longer a question of telling Africa to Europeans, as I did in Spain, but of telling the African reality to Africans themselves, with the intention of making them aware of the challenges of the continent and the need for them to get involved in the transformation of society.

The difficulties we face are due to the socio-political reality of the countries where our journal is published.

There are few readers because of illiteracy, little interest in reading among most people and because of poverty.

As journalists, our work requires a lot of time to read and get in touch with reality. So, it is hard to talk about things you have not seen, touched, or felt. We see this reality on a daily basis and touch it through our contact with people. That is why we go out, even outside our borders, to ask people about their experiences. We visit them in parishes, hospitals, schools, public offices, centres, etc. They have stories to tell and experiences to share. In turn, we have the mission to make this known to the readers.

The use of the means of communication is a constituent element of evangelization as enshrined in the Comboni missionary strategy. Through the magazine and books published by Afriquespoir, we transmit the Good News and we contribute to the intellectual, spiritual and missionary formation of the People of God.

This requires us an attitude of listening. Listen with the heart in order to speak with the heart, as Pope Francis encourages. It is listening to the reality that surrounds us, the people I meet in the streets or in the parishes, those I interview or photograph, listening and treating with respect the people who share with me their stories so that

I can tell them to the readers.

As a Comboni missionary brother journalist, I am happy with my mission. I proclaim the gospel through magazines, books, radio and television shows, social networks and web pages. I feel invited, as a journalist, to be faithful to the Gospel and improve the quality of my service; to be a good journalist and a good missionary.

Sr Lilia. How to be a missionary.

I am Sister Lilia Navarrete Solís from Mexico. When I was small, my mother and aunt often took me to a Salesian chapel near our house. I was part of the choir and on one occasion a lady came to tell us about an African country that was at war at the time. Listening to her, I thought: “I would like to go to a place like that, where I can give meaning to my life and for which it would be worth leaving everything”.

Leaving the church, the lady gave me a flyer from the Comboni Missionary Sisters with an address on the back. I was very young and didn’t have the courage to ask her for more information, but I took that paper with me and kept it as a treasure. Over time, I began studying nursing and working to help the family economy.

One day, curiously, my work took me to a parish where someone gave me another booklet from the Comboni Sisters. It couldn’t be a coincidence. So, I decided to contact the missionaries. From then on, I began to participate once a month in vocational meetings and, when I finished my studies, I asked to enter the Institute.

My mother didn’t accept my choice to be a missionary, but since the training was in Guadalajara and I didn’t have to leave Jalisco,

she was satisfied.

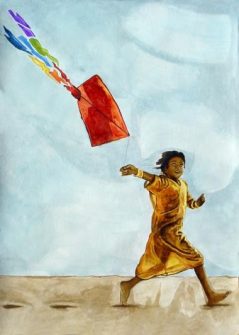

At the end of this first stage, I was sent to Brazil to continue my formation. After three years I returned to my family to say “yes” to the Lord and consecrate my life to the mission. My joy was even greater when I was assigned to Mozambique.

I thought I was ready for a mission in Mozambique, but I soon realized it would be the people who would teach me how to be a missionary.

I remember that in Magunde, in the province of Sofala, I had an encounter that changed my life. A woman came to the maternity ward where I worked as a nurse, and since there were no doctors, I delivered her baby. While she rested, I bent down to examine the baby. She saw the cross I was wearing, took it in her hand and asked me: “What is it?” I don’t remember my answer, but I do remember my surprise that she didn’t know Jesus Christ I was with her when she gave birth and I felt I was in the right place.

Five years later I had to leave Mozambique to continue my nursing service in Italy, accompanying elderly and sick nuns. During the pandemic, I did everything possible to prevent the virus from entering our home, even though the virus did take away some of our sisters.

Since last year I have been in Spain working in youth ministry and in mission promotion. I am also happy to see this assignment as a continuation of God’s work in me. The “yes” that I pronounced before the Lord on the day of my consecration as a Comboni missionary continues to be strongly alive in me. I have received more than I could give.

Fr. Aldrin. Working together with the people

I am Fr. Aldrin Janito, one of the pioneering Filipino Comboni Missionaries. I was born in Kiamba, South Cotabato, in the south of the country. In June 1991, I started my journey with the Comboni Missionaries. While undergoing my postulancy formation, I also graduated in Philosophy. Then I went to the Novitiate in Calamba, making my first profession in May 1995. I continued my theological formation at the International Scholasticate in Nairobi, Kenya.

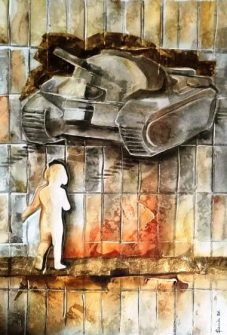

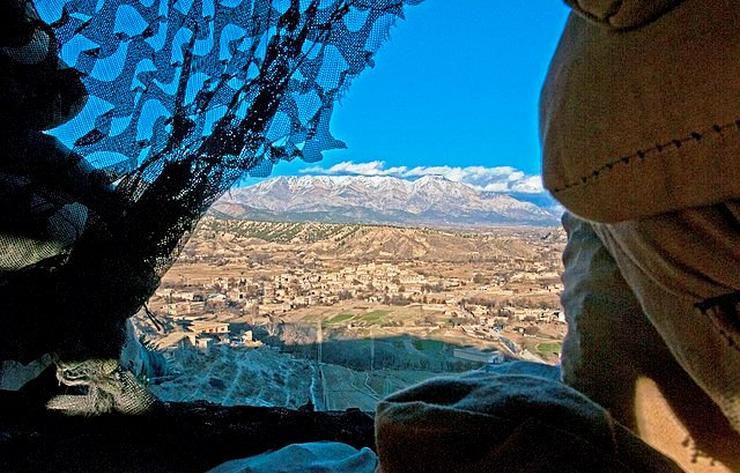

I was ordained into the priesthood on June 7, 1999. After my ordination, I served as a vocation promoter from 1999 until 2003 in my country. I was assigned to Sololo missions, Diocese of Marsabit in Kenya from 2003 to 2004. This two-year missionary service marked my life after witnessing the killing of my Kenyan people, who were mostly church leaders and infants. It was a horrible experience but it did not kill my missionary spirit. My last assignment was in South Africa where I spent 16 exciting years in two parishes, Waterval and Acornhoek.

Serving in these two parishes as the priest-in-charge was not easy. Some challenges I met included ancestor worship, several languages spoken in the area, sustaining the spirit/church commitment of the youth during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, the poor service delivery of the local government, rampant alcohol and drug abuse, criminality, such as stealing, teenage pregnancy, poor literacy,

HIV/AIDS, and unemployment.

As a parish, we tried to address these pressing issues by using alternatives, such as mobile catechesis (reaching people whenever they are), supplementary education and tutorial services after school, HIV/AIDS support group, setting up orphanages and drop-in centres, promoting ecumenism with other sects and local churches,

Sunday school, etcetera.

As an administrator of these parishes, I learned how to listen and exercise patience. As a Swahili saying goes, “hara haraka haona baraka,” meaning he who runs fast runs alone. The spirit of “Ubuntu,” of working together with the people, is essential. A missionary who learns several languages without learning the local culture and customs of the people risks of becoming a fluent fool.

My participation in the Comboni Year in Rome, Italy (2013-2014) strengthened and renewed my missionary spirit in Limone, Italy, home of our founder and father, St. Daniel Comboni.

Coming back home to serve the Philippines, in my delegation of origin as the new mission promoter, is fun and challenging.

Basically, to share one’s missionary experience with the people, stimulate interest, and lift their spirit by supporting and sustaining the mission of Christ, near and far.