African Music. Creativity and the Internet.

Afrobeats, bongo, amapiano, rumba, and gengetone are genres that are now heard everywhere. Thanks to social media and the growing investments of the recording industry. The world has never heard so much African music as today.

Over the last decade, African music has risen to the forefront of the international scene. Out of all of these, it was Afrobeats, the genre born in Nigeria, that showed the way, with artists like Burna Boy increasingly achieving sell-outs, climbing the charts, and winning awards. However, the music of the continent has much to offer beyond Afrobeats.

There are several genres that are increasingly capturing the interest of the global public: the amapiano from South Africa, the bongo from Tanzania, the rumba from the Democratic Republic of Congo, or the gengetone from Kenya, but also the African declinations of genres such as R&B and drill music. It is safe to say that African music is entering

its ‘golden age’.

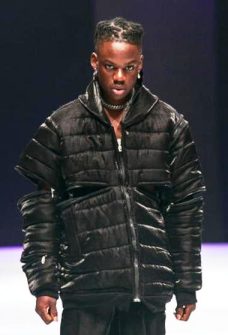

Divine Ikubor, known professionally as Rema. On 26 October 2023, Rema released a 5-title EP named Ravage. CC BY-SA 4.0/ Thealfe Studios

In 2023, for example, the Afrobeats category was included in the MTV Video Music Awards for the first time. Taking a look at the artists nominated for the statuette allows you to get a precise idea of the exploits this style has recently performed. Virtually impossible to escape, anywhere in the world, is Rema’s Calm Down, as well as her remix with Selena Gomez.

The two versions of the song have totalled 1.1 billion views on YouTube. Davido’s Unavailable is the lead single from Timeless, the Nigerian artist’s fourth studio album, and the first album by an African songwriter to reach number one on the US iTunes chart. Then there is Burna Boy, with his hit It’s Plenty. The Nigerian singer’s seventh LP, I Told Them, reached number one in the English charts: just the latest in an endless series of recognitions. Moving forward we find Bandana, by Rema and Fireboy DML, one of the anthems of the year 2023, and then People, another great success of the same year, by Cameroonian Libianca.

TikTok

How did this explosion arise? Several factors have contributed to the enormous increase in the global consumption of African music. Above all, the internet and social media, have given a decisive boost to the international public’s access to the music of the continent. YouTube, and more recently TikTok, have played a crucial role in taking African music to a new level. YouTube has made many listeners discover African

songs for the first time.

Selena Marie Gomez, singer, actress, businesswoman and producer at the 2023 MTV Video Music Awards. CC BY-SA 4.0/Vmas

And, in recent years, TikTok has been a launching pad for the careers of quite a few artists. With short-form dance videos dominating the social media platform, their songs have provided the perfect soundtrack for millions of people

around the world.

The platform’s data reveals that Rema’s Calm Down has been used in 1.8 million videos; Ruger’s Girlfriend in 1.5 million. “For listeners, TikTok is now one of the main tools for discovering new music”, emphasises Emmanuel Okiri, strategist of the music and entertainment platform Loud.co.ke. based in Nairobi: “When developing strategies to launch their songs, many African artists focus on the most effective ways on the platforms, such as viral challenges and collaborations with influencers”.

Major and local labels

Not only ordinary fans have become enthusiastic about African music. Reading the current trends, major record companies have started investing in artists from the continent like never before. Over the past six years, Universal Music Group, Sony, and Warner, the three major labels that alone control around 69% of the world’s record market, have all added African talent to their stables.

The biggest names in African music, such as Rema, Davido, Burna Boy, and Wizkid, have all signed contracts with major labels. The latter are also entering into partnership agreements with local labels, thus creating a channel that can bring emerging African talent to the global spotlight. Of course, the revenue generated by African music has also grown.

Afrobeats star Burna Boy performing at Nativeland Concert, Lagos, Nigeria. CC BY-SA 4.0/Catherine Omeresan Sutherland.

According to data from the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), artists in sub-Saharan Africa produced $70.1 million in revenues from recorded music in 2021, an increase of 9.6% year-on-year. Today, the main revenue sources for African musicians are live performances and streaming. For the more successful ones, brand partnerships are also proving profitable.

Between August 2021 and August 2022 Apple Music recorded a 500% increase in streaming from African DJs. Also in 2021, Spotify decided to expand to reach 39 African countries, in order to tap into the vibrant musical genres that are redefining the continental scene. Research by the Dataxis centre estimates that annual revenues from African music streaming will increase in 2026 to 314.6 million dollars, from 92.9 million in 2021. Unlike the IFPI data, which only takes sub-Saharan Africa into consideration, Dataxis considers the entire continent including North African markets.

Royalties

However, several factors could hinder the expansion and development of the great financial potential of African music. First is the low network penetration rate recorded on the continent. In its research, Dataxis estimates that this will represent the first limit to the growth of the sector, underlining that ‘streaming cannot go faster than infrastructure’. Improving this aspect can therefore act as a driving force for the entire sector. In the growth of African music consumption, the transnational diffusion of various genres on the continent has played a central role, and Nigerian Afrobeats, for example, is very popular in Kenya, as confirmed by the data on streaming listeners – unlike Kenya which is one of the African countries where the diffusion of the network is more widespread. Observes Okiri: “If we could improve internet access on the continent, the impact would also be felt in all creative sectors, not just music. The benefits for cinema or video games, both of which use music in various ways, could be significant”.

“If we could improve internet access on the continent, the impact would also be felt in all creative sectors, not just music.” 123rf.com

The growth of the African music industry is also being held back by the limited support for artists in some of the continent’s biggest markets. Musicians lose millions in royalties due to inaccurate collection systems, mismanagement, and lack of accurate data. A forensic audit of organizations in Kenya responsible for collecting and distributing royalties to artists has revealed that between 2020 and 2022, musicians did not receive the $1.07 million they were owed. Although the organizations collected licensing fees from the various businesses that used the music, the money never reached the artists, who often found themselves in poverty. Investments and policies that increase internet access in Africa and ensure fair wages for artists should therefore be priorities for African governments. Only in this way will music and entertainment become pillars of African economies, generating thousands of jobs and valorising a large number of artists. (Open Photo:123rf)

Martin Siele