South Korea. Pots, Rice and ‘the Have-Nots’ of Seoul.

Left a very poor country after the end of the Second World War, South Korea is today at the forefront on a technological, economic, and social level. However, it exists in a world marked by profound contradictions in which young and old remain on the margins, as Father Vincenzo Bordo says from the capital.

“Here everything is rapidly changing and the Korea that I saw when I arrived in 1990 no longer exists, it is another nation, it is almost unrecognizable”. This is what Father Vincenzo Bordo of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate says from Seoul, in what has become his city for 34 years and where many know him for his work on behalf of the marginalized: from soup kitchens to shelters for children on the street; and from accompanying the sick and lonely to assisting the elderly. It is a world of people in difficulty living in the shadow of one of the most technological, richest, and futuristic cities in Asia; the iconic capital of one of the ten most industrialized nations on the planet.

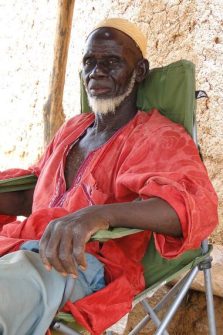

Fr. Vincenzo has set up a canteen that serves about 500 meals a day. Photo OMI

Father Bordo recounts the incredible “economic development of these decades, accompanied by many social changes. What is noticed less but has the greatest impact is the cultural change, viewed in a positive way when you observe the affirmation of ‘K culture’: songs, films, food, and widespread well-being. But we can also see its negative side if we focus on other data: South Korea is the country with the highest number of suicides and the lowest birth rate; there is a high divorce rate (around 30%) and a very rapid ageing of the population, with elderly people often alone and in marginal conditions. But what is most noticeable is the transition from the culture of ‘we’ to that of ‘I’ “.

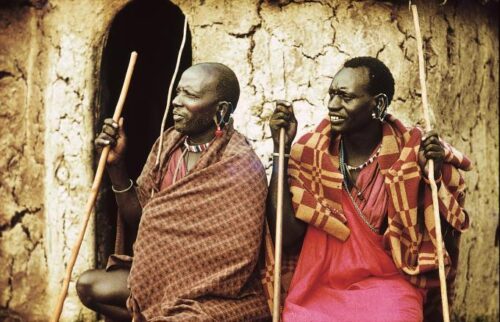

The missionary recalls the values that made him fall in love with these people: the ability to sacrifice for the community, for the nation, the devotion, and the popular religious soul – “great values that no longer exist today”. “When I arrived, there was a very strong sense of belonging, everyone was committed and sacrificed for the good of the community. Now what matters is nothing but happiness and personal fulfilment. Korean society is becoming more and more individualistic, closed in on itself, and pays little attention to development in common with others”.

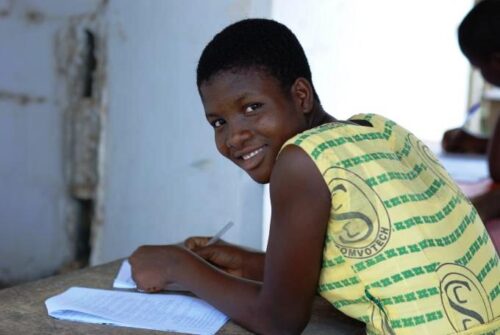

Young people live at a fast pace. Photo: Pixabay

Life in the southern part of the Korean Peninsula is very different from that across the border marked by the famous 38th Parallel, that is, from the North Korea of dictator Kim Jong-Un and his regime. After Japan’s defeat in the Second World War in 1945, the Asian country was divided into a zone of US influence (the Republic of Korea with its capital in Seoul) and a pro-Soviet zone (the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea with the seat of government in Pyongyang). Since then, families separated by a conventional border have lived in two parallel and very different cultures that have shaped lifestyles and political, economic, and social systems that are much different from each other: one is the capitalist, Western and democratic in the South; in the North, we find the state-based, totalitarian system that holds the record for investments in weapons. After the clashes of the Korean War in 1950, an armistice was signed, but peace was not formalized. A large strip on the border between the two states remained militarized and mined three kilometres deep in the north. Despite everything, however, relations between the parties remained fluctuating, with moments of rapprochement and air alerts in Seoul due to the missiles launched by Pyongyang.

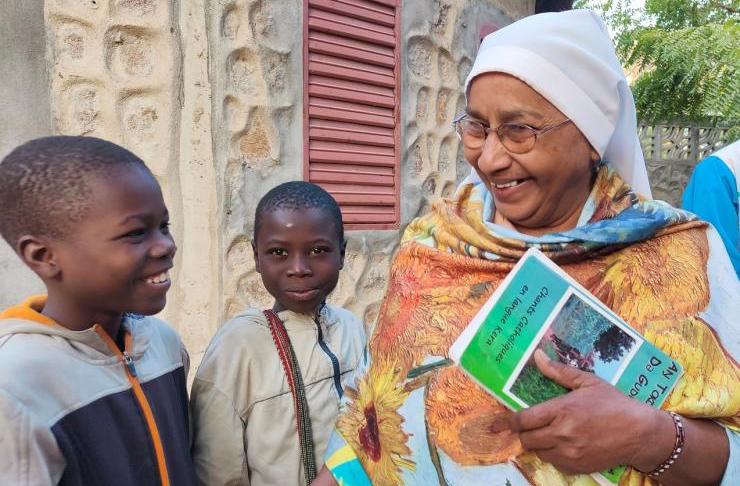

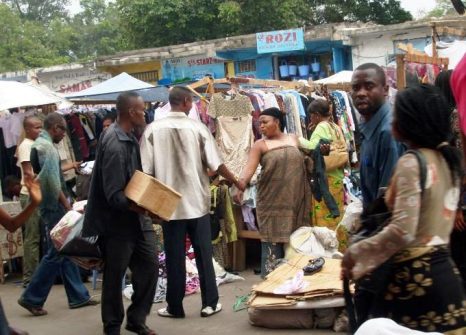

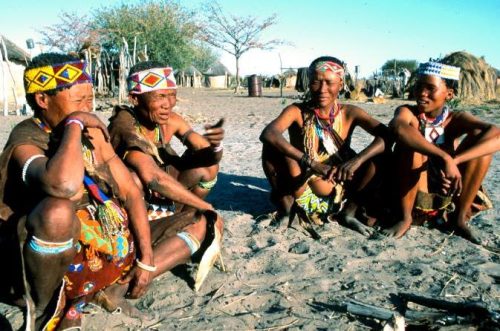

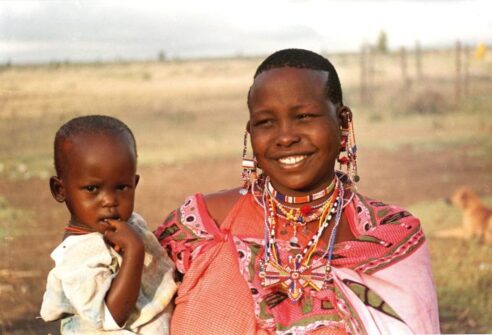

Anna’s House. A non-profit organization that welcomes homeless and marginalized people, lonely elderly people, and street children. Photo OMI

But now few remember the division that occurred almost 70 years ago. “People have other things to worry about, they have forgotten – explains Bordo -. North Korea launches many missiles, sirens are heard, and people have to take refuge in cellars and shelters. But they know that if there was a nuclear attack from the neighbouring country, this would be the first to be wiped out. Even the fact that the post-war armistice between the two Koreas was never completed by a declaration of peace is of no interest to anyone. While we are talking, people are walking about, and the streets are full of youngsters talking on their cell phones and listening to music”.

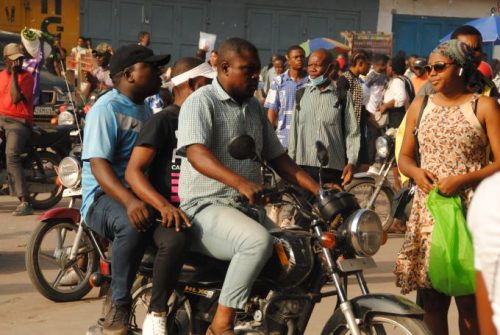

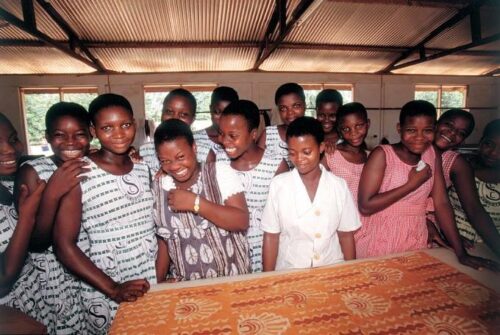

In Samsung’s Korea we live according to Western standards of life and the youngsters are children of modernity, of a globalized culture that goes beyond states and continents. And in what was a young country, the birth rate has now plummeted, and the population is ageing at a rapid rate. “Now the young people are individualists, capitalists, consumerists – Father Vincenzo continues. – Young people who get married don’t want to have children. They live at a fast pace; contemporary civilization is articulated, complex, and without respite. Anyone who can’t keep up with the pace stays out: solitary and ageing street children, lonely and marginalized people. These are the new forms of poverty in a rich world”.

Seoul. “In Samsung’s Korea we live according to Western standards of life and the youngsters are children of modernity”. Pixabay

Father Vincenzo knows these realities well and has set up an assistance network with six homes for the homeless, and a canteen that offers around 500 meals a day to people who in 70% of cases have only one meal a day. Then there is the “Anna’s House “, a non-profit organization that welcomes homeless and marginalized people, lonely elderly people, and street children. Father Vincenzo explains that “Many marriages end in divorce and the children are entrusted to the father who often finds it difficult to manage the children alone. When he remarries and has children with his new wife, she takes care of her children and neglects the others. Most kids end up on the streets due to family violence. We do a lot of psychological therapy and recovery programs to help them get a diploma so they can work and fit into society. The problem is to help them regain confidence in the adult world. We have a travelling team on a bus. We don’t wait for them to knock on our door, we go out and look for them”. (Open Photo: Seoul. Downtown shopping street. Pixabay)

Miela Fagiolo D’Attilia/PM