A Turkish fleet of power stations comes to Africa’s rescue.

Africa has the lowest access to electricity in the world. For a few years, a Turkish company that owns a large fleet of powerships that dock at the harbors and connect to the national grid. Critics claim that the solution is not sustainable and expansive. But the company delivers as long as countries pay their bills. Otherwise, they can be switched off.

Approximately one century after the sunset of the Ottoman empire in 1922, Turkey is back on the African continent, in a powerful way. On a continent where half a billion people lack access to electricity, a Turkish fleet of power ships is providing a unique solution for coastal countries that lack infrastructure.

A company called Karpowership, owned by the Karadeniz Holding whose CEO is Orhan Remzi Karadeniz launched indeed in 2007 a project called “Power of Friendship”, which supplies electricity to shortage-stricken countries in the Middle East, Africa and Asia.

Karpowership supplies electricity to shortage-stricken countries in the Middle East, Africa and Asia. Photo: Karadeniz Holding.

So far, Karpowership which has operated in Iraq, Sudan, Pakistan, Lebanon, Indonesia, Cuba, has built a 6,000 MW installed capacity on its 36 Powerships. Floating Storage and Regasification Units (FSRU), LNG Carriers and Support Ships. Such capacity is simply enormous. It amounts to the equivalent of the future total capacity of Africa’s largest hydropower plant: the Renaissance dam on the Blue Nile in Ethiopia.

These vessels are barge- or ship-mounted floating power plants which can operate on heavy fuel oil (HFO), diesel fuel or increasingly natural gas. The power is available under electricity-generation services contracts, power-rental contracts, energy-conversion works contracts, or power-purchase agreements.

Around Africa

Orhan Remzi Karadeniz’s company is namely active in the countries that are the most in need and where it has managed to become the main provider. The list includes Gambia, where Karpowership signed a contract in 2018 with the National Water and Electricity Supply Company to deploy a 36 MW powership which is still operational and has been supplying 60% of the country’s total electricity needs.

In Guinea-Bissau, Karpowership deployed in 2019 a powership of 35 MW which is supplying 100% of the national electricity needs, while in neighbouring Sierra Leone, a 65 MW capacity has installed and generates 80% of the power distributed by the Electricity Distribution

and Supply Authority (EDSA)

The vessels are barge – or ship- mounted floating power plants that can operate on heavy fuel oil (HFO), diesel fuel, or increasingly natural gas. Photo: Karadeniz Holding.

Karpowership is also important in other countries of the region. It has signed a Power Purchase Agreement with the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG) for the supply of 450 MW of electric power and it has been operational there since 2015, supplying 23% of the total national needs. Since 2022, Karpowership is also operational in Côte d’Ivoire where it is generating 100 MW of electricity, representing 7,5% of the country’s total needs.In August 2019, Karpowership signed an LNG-to-Power contract with Senegal’s Electricity Authority (SENELEC) to deploy a Powership of 350 MW which corresponds to 15% of Senegal’s total electricity needs. In 2021, a Floating Storage and Regasification Unit (FSRU) constructed in a 50/50 joint venture between Karpowership and Japanese firm Mitsui OSK Lines,called KARMOL, arrived in Dakar.

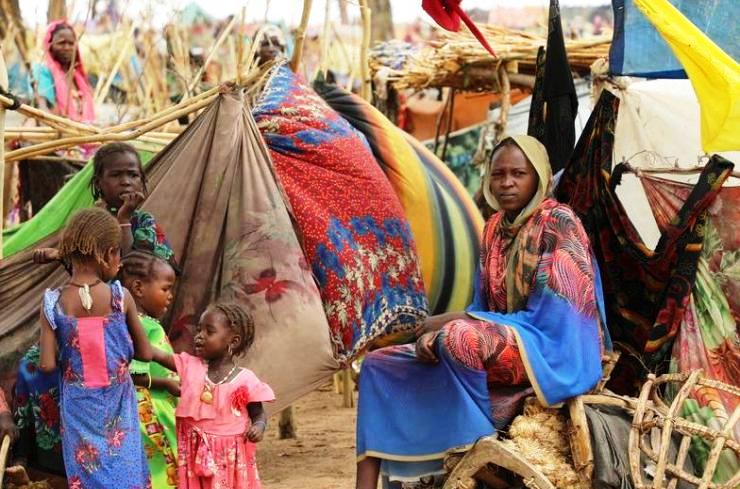

Karpowership is operational since 2018 in Mozambique where it signed also a contract with Electricidade de Moçambique (EdM), to deploy a Powership of 125 MW. In the past, between 2019 and 2023, Karpowership was also operational in Guinea-Conarky where it supplied 105 MW, amounting to 10% of the country’s needs besides other contracts in Sudan and Zambia.

New Supply Contracts

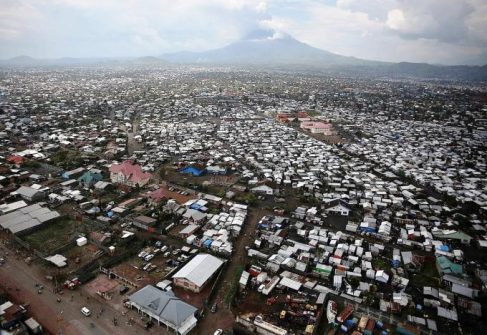

New markets are being explored. In October 2022, the Regulation Authority of Electricity (ARE) of the Democratic Republic of Congo approved a concession to Karpowership for the installation of a 200 MW floating power plant in the port of Matadi. On the November 17, 2023, the company’s chief commercial officer, Zeynep Harezi, told the Semafor Africa news platform that Karpowership expected to begin operating in South Africa in the second half of 2024 after winning a tender to generate 1,220 MW of LNG-to-Power were named as winning bids for 3 projects – about 2% of the country’s energy supply. According to Harezi, the company is now engaging with the authorities of Tanzania, Kenya, Gabon, Cameroon and Liberia to sign new supply contracts.

Turkey has sold Bayraktar TB2 drones to Ethiopia, which has used them in its war against Tigray. CC BY-SA 4.0/Bayhaluk

This spectacular expansion fits in Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s wider strategy in Africa. Indeed, alongside Turkish Airlines which is planning to fly to 62 African destinations (instead of 44 in 2021) and reinforce its leading position on the continent, Karpowership is one of the most important ambassadors of Turkish diplomacy in that part of the world, alongside with the arms exporters. Indeed, Turkey has been aggressive on that front, selling Bayraktar TB2s drones to Ethiopia which used it in its war against Tigray and Nurol Makina armoured personal carriers sold to the Senegalese gendarmerie. Obviously, such diplomatic, commercial and military breakthroughs irritated former colonial powers. Before she left her job in May 2022, the former French Defence Minister Florence Parly accused Turkish troll farms and the Anadolu News Agency of carrying out disinformation campaigns and French bashing.

Meanwhile, the Turkish offensive in the energy sector does not always look like a rosy picture. Indeed, in recent months, Karpowership cut off electricity in Freetown and Bissau after the authorities failed to pay bills reportedly totalling $40 million and $17 million respectively. Last September, In Freetown, the switch-off by Karpowership reduced electricity supply to the capital by 13%. Electricity was rationed with homes and businesses going without power for hours daily. Likewise, on the 17 October, Bissau was plunged into darkness.

Eventually, the power was restored after a few weeks in both countries and the supply contracts were renegotiated as part of a deal under which Karpowership supplies them with less electricity. These incidents highlighted however the vulnerability of the customers in the event of a dispute with the power provider.

Sierra Leone. Freetown Harbour. Last September, in Freetown, the switch-off by Karpowership reduced the electricity supply to the capital by 13%. 123rf

Karpowership has also faced a hostile campaign waged by South African environment activists which launched a petition in 2021 urging the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA), ABSA and Investec banks not to invest in Karpower’s gas-to-power ships because such deals tie “South Africa into a future dependent on climate-damaging fossil fuels” accordingly. These critics also claim that the pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from these ships exacerbate climate change and limit South Africa’s ability to tackle the climate crisis. Besides, they say, the 20-year contract will make electricity more expensive as the Karpowership tariffs depend predominantly on imported fossil fuels. The authors of the petition claim that cheaper and cleaner electricity are available at 75c/kWh (wind) or 91c/kWh (solar), as against R1.36/kWH for Karpowership SA Coega: R1,36/kWh.

South Africa. View of Cape Town at night from Signal Hill. Environment activists accused the Turkish company of entering new markets by paying large facilitation fees to politically exposed persons which could be construed as bribery.123rf

Other critics are questioning Karpowership’s ethical attitude. They stress that the Turkish company has a practice of entering new markets by paying large facilitation fees to politically exposed persons which could be construed as bribery. They remind that in Pakistan, a Karadeniz subsidiary allegedly paid middlemen to secure a $565 million government contract.

The Supreme Court voided the contract in 2012 and launched a corruption investigation. But eventually, the matter was resolved in 2019 through political negotiations between Pakistan and Turkey.

In South Africa, a losing bidder made corruption allegations against Karpowership and a government official. But Karpowership and its local partners denied the allegations while the Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme said the losing bidder had been disqualified because its bids fell short of requirements. Karpowership also retorted to critics that their allegations were “completely incorrect and unsubstantiated”. (Open Photo: Karpowership. Karadeniz Holding).

François Misser