Antigua Guatemala. Holy Week

The ancient capital of Guatemala, a baroque jewel among the mountains, is the scene of spectacular processions on carpets of flowers in the days before Easter. Holy Week is not just devotion, it combines faith, religiosity, art, gastronomy, life stories

and mutual help.

Evocative processions pass through the streets of the historic centre covered with elaborate carpets of flowers: Holy Week in Antigua Guatemala is an event that involves the entire community, between popular devotion and artisanal skill handed down from father to son.

Antigua, as the town is also known, was founded with the name of Santiago of the Knights of Guatemala at the beginning of the 16th century by Spanish colonists who made the capital, at 1,500 meters above sea level, an important cultural, economic, religious and political centre, lasting until 1773 when, following an earthquake that largely destroyed it, the capital was moved to Guatemala City. But the ancient one – Antigua itself – was rebuilt on a grid model inspired by the Italian Renaissance, with new monuments and superb Baroque churches, whose beauty adds to the charm of the ruined historic buildings, so much so that UNESCO has declared the city a World Heritage site. But it is in the days before Easter that streets and squares come alive, with a collective celebration of the passion and death of Jesus: the churches host vigils while the streets are covered with splendid carpets of flowers and coloured sawdust to welcome the processions.

Antigua, Guatemala – Man wearing purple robes in a Holy Cross procession. 123rf

The introduction of processions is closely linked to the arrival of the Spanish in the territory and was one of the evangelisation activities carried out by the missionaries who accompanied the conquistadors. With the processions, the first images and the first small floats emerged, created by Guatemalan artists. Initially, only six to eight people were required to transport the wagons. The event has grown in all its aspects and today the largest procession in the world, that of Calvary (linked to the Church of Our Lady of Remedies), has a float of approximately 26 meters, which is transported by 140 people who take turns carrying it leading the way through the streets of the city. Blood processions once existed, in which penitents walked with their faces covered and their backs scourged along the route, but they quickly died out. Holy Week processions in Guatemala are so important for the population that they can last up to eighteen hours without interruption.

Processions and the Confraternities

In Antigua, the first processions take place on the Thursday after Ash Wednesday, continuing throughout Lent. They navigate the streets of the city, starting from a church and returning to the same place. One of the things that must not be missing in any Lenten or Easter procession in Guatemala is the processional carpets. They are made with coloured sawdust, flowers, fruit and pine cones.

The streets are covered with splendid carpets of flowers and coloured sawdust to welcome the processions.123rf

Also fundamental to the procession are the ornaments such as the cross, candles, images or banners of the brotherhoods responsible for the organization. Incense hovers in the air, devotees carry floats called cucuruchos from the cone-shaped hood they wear – and the essential brass band plays both funeral marches as well as festive tunes. We carry with us the awareness that the celebration is double, that of the passion and death of Christ, but also of his resurrection, a source of hope and life that continues.

An important role is played by brotherhoods, composed of people from all social backgrounds. They wear colourful clothes that vary depending on the day: black – for mourning – on Friday, purple on the remaining days of Lent. They carry huge platforms with images of Jesus, Mary and, in some cases, angels and/or their patron saint.

Antigua Guatemala. People with pointed hood costumes carrying paintings of the way of the cross at the procession of San Bartolome de Becerra. 123rf

The carrier formations alternate along the route. Every bearer sees this as a very important moment. The task of carrying the image is sometimes passed down from generation to generation. Other members of the brotherhood burn incense in thuribles along the route.

The most evocative moment is Palm Sunday, when men dressed in purple tunics, the cucuruchos, come out of the Church of La Merced holding up a canopy with the statue of Christ, followed by women, carcadoras, holding an image of the Blessed Virgin.

The Female Figure in Holy Week

The female figure in Holy Week has played an important role from the beginning. Proof of this is the coronation of Nuestra Señora del Manchén (Our Lady of Sorrows) in 1738. This sculpture shows the pain of the Mother of Christ during her passion. Created in 1660 and exposed for veneration on Good Friday of that year, she is venerated in the homonymous hermitage of Santiago of the Knights of Guatemala.

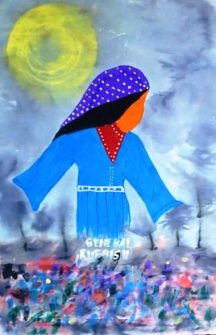

Antigua Guatemala. The female figure in Holy Week has played an important role from the beginning. 123rf

The image shows the maternal face of pain and reveals the model of female holiness, that of the Mother of God. Some of its characteristics make it a unique image, it is the first Image of the Consecrated Blessed Virgin in America and the second image to be consecrated in Guatemala 21 years after Jesus the Nazarene of la Merced in Guatemala City.

In 2022, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) approved the inclusion of Guatemala’s Holy Week in the World Heritage List because, as we read, “It is a religious and cultural celebration that forges the identity of Guatemalans around an expression of their faith, promotes tolerance, respect and social cohesion in the territories in which it is present.”

Pedro Santacruz