The Catholic Church. “A laboratory of evangelization in a Buddhist world”.

Under the Pol Pot regime, the Church lost everything: bishops, priests, men and women religious and catechists. Since the 90s it has emerged from the catacombs and is slowly growing in numbers as well as

in social commitment.

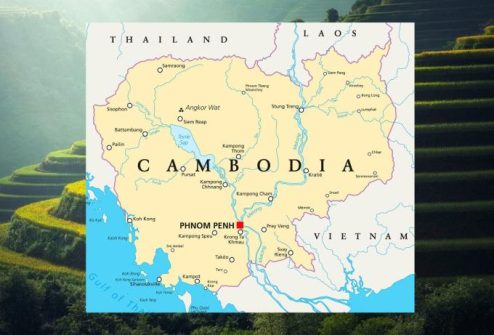

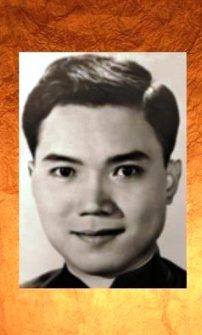

Monday, April 14, 1975, was an overcast afternoon. From his window, Father Joseph Chhmar Salas watched as people with their few belongings fled from the ferocity of the Khmer Rouge. He had recently returned from Paris where he was on sabbatical, after having received a letter from Bishop Yves Ramousse asking him to return. Leaving the seminary of the Missions Étrangers in Paris he had no illusions, “I’m going to Cambodia to die there,” he said to his brothers but he obeyed the bishop and immediately returned to the country. Foreign missionaries had left the country. It was necessary to have a bishop in the country who could continue the mission of the Church.

Since the capture of Phnom Penh by the Khmer Rouge was imminent, his episcopal ordination was brought forward. There was already a curfew in force in the city so he was consecrated that same evening and appointed coadjutor bishop of the Apostolic Vicariate of Phnom Penh.

Bishop Joseph Chhmar Salas, coadjutor bishop of the Apostolic Vicariate of Phnom Penh. He died in a forced work camp of the Khmer Rouge. He was the first Cambodian native bishop. File archive

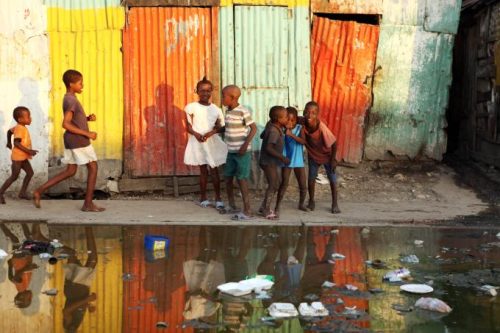

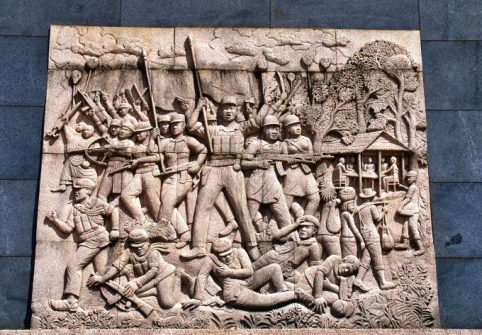

Three days later, on April 17, the Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh and evacuated the entire population, including the sick, the elderly and the children. The genocide began which would cause one million seven hundred thousand deaths, including that of the new bishop. All the leaders of the Catholic Church and evangelical pastors were either killed or died of starvation under Pol Pot. All churches, convents and cemeteries were systematically razed to the ground.

Pol Pot’s regime fell in 1979 but the Church was forced to continue to exist underground. Only in 1990 did the first faint glimmers of religious freedom begin to appear and the first outdoor acts of worship were held despite enormous difficulties.

The Church, however, was still under strict surveillance. Each community had to draw up a monthly report and the local authorities sometimes asked for a list of the Christians. In 1993, the new Constitution also granted freedom to non-Buddhist religious denominations. In March 1994 diplomatic relations were established with the Holy See and the Council of Ministers approved the statutes of the Church in 1997.

The Cross of Mons. Salas

However, the Catholic community does not forget the horrors of persecution and the death of so many Christians and every year, on June 17, the small community of Catholics living in Cambodia remembers the Christians who testified to Christ by giving their lives in the years when the Pol Pot and Khmer Rouge oppression raged: Monsignor Joseph Chhmar Salas and 34 priests, lay people and catechists, Cambodian, Vietnamese and French missionaries, for whom the Cambodian Church opened the diocesan phase of the beatification process in 2015.

Monsignor Olivier Schmitthaeusler, MEP, Apostolic Vicar of the capital Phnom Penh. (Photo: Apostolic Vicariate of Phnom Penh)

During the commemoration last year which was held in Taing Kok, in the centre of the country, where Monsignor Salas had celebrated the Eucharist until his death in 1976, Monsignor Olivier Schmitthaeusler, Apostolic Vicar of the capital Phnom Penh recalled: “Every year the Church is called to celebrate this anniversary. Earthly life is a time to give glory to God on Earth and the testimony of the martyrs guides us on the way.” Monsignor Schmitthaeusler noted that the cross given to Monsignor Salas during his pastoral ordination on September 14, 1975, three days before the start of the genocidal regime of the Khmer Rouge, has been preserved and handed down over time.

After his death, his mother kept it and later entrusted it to Monsignor Emile Destombes, Apostolic Vicar of the capital from 1997 to 2010, who in turn handed it to him.

A Church that touches the heart

Cambodia has just over 17 million inhabitants and around 95% of the population is Buddhist. Monsignor Olivier Michel Marie Schmitthaeusler explained: “The small Church of Cambodia is in some way a laboratory of evangelization in a Buddhist world that has fully adhered to the process of secularization brought about by globalization, a bit like the Asian dragons.” He indicated how the Church should be, to reach out with the new evangelization: “A Church that touches the heart, a simple Church, a hospitable Church, a praying Church, a joyful Church.”

The Catholic Church in Cambodia has 14 native priests and around 150 foreign missionaries. (Photo: Apostolic Vicariate of Phnom Penh)

Monsignor Schmitthaeusler indicated how to “Build our Church, a sign of the Kingdom of God”, in ten points: “Spiritual life: we are born of God and sent into the world; communion among us; inclusion for all: everyone is welcome; forgiveness: a sine qua non condition for moving forward; a heart that listens and loves in action and in truth: charity in action; true and direct dialogue at all levels: religious, institutional, social; concrete presence in society; the integral formation of just and virtuous men and women; the heart of a father and mother: the Church is a family… a giant tree with a huge heart; be creative: the Gospel is new every morning”. “Yesterday, today, tomorrow: the Church is 2000 years old and it has roots that nourish ours today and prepare the future – recalled Mgr. Schmitthaeusler -. No one is indispensable, we are mere worthless servants who offer more love and life and who can withdraw discreetly knowing that others continue this service of announcement and peace; the Church was, the Church is, the Church will be”.

Sunday Mass. “To listen to the Word of God”. Photo: Photo: Apostolic Vicariate of Phnom Penh)

Looking forward to the Jubilee Year of 2025, Mgr. Schmitthaeusler invited the Cambodian Catholic community to listen to the Word of God: “To prepare for the Year of Jubilee, 2025, which will be a year of mercy and grace from the Lord, let us take time to pray. Prayer is the foundation of all things, the foundation of conversion, the foundation of our vocation through listening to the Word of God, the foundation of every activity of the Christian community.”

Currently, the Catholic Church in Cambodia has 14 native priests and around 150 foreign missionaries who provide pastoral service in more than a hundred parishes throughout the country.

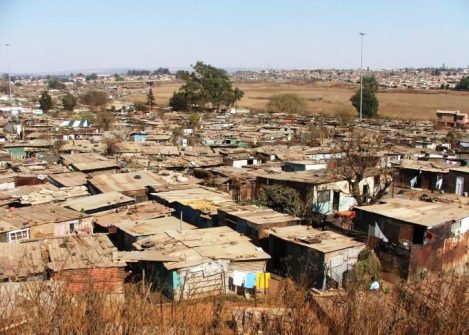

There are three ecclesiastical districts: the Vicariate of Phnom Penh and the Apostolic Prefectures of Battambang and Kompong Cham, and overall, there are around 20,000 Catholics. (Open Photo: Apostolic Vicariate of Phnom Penh)

François-Xavier Demont/MEP