The Arctic: becoming increasingly strategic.

Access to Arctic shipping routes is not only a commercial opportunity, but also a matter of strategic security. For countries such as Russia, China and the United States, controlling these routes would give them a significant economic and geopolitical advantage. The importance

of Greenland.

Greenland, a remote island located beyond the Arctic Circle, is increasingly becoming a global geopolitical focus. This is partly due to global warming, which is accelerating the melting of ice and unlocking vast natural resources that were previously inaccessible. These include strategic materials such as rare earth rare metals, gas and oil, which are essential for the development of new technologies in key sectors, including digital and renewable energy.

The warming of the ice sheet is also opening up new shipping routes, which could revolutionise international trade, shorten distances and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. However, Greenland is also vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

“Polar amplification” is causing temperatures in the Arctic region to increase at twice the rate of the global average, with serious impacts on local living conditions. Greenland’s indigenous communities are facing changes to their habitat, with potentially devastating economic, social and environmental consequences.

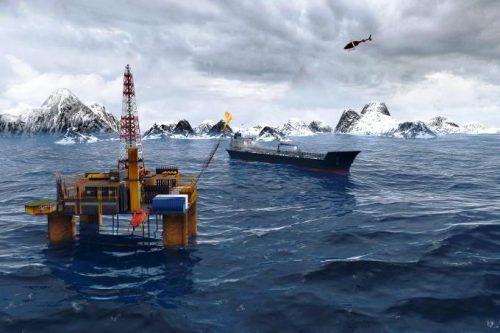

Oil platform in the Arctic Ocean. Shutterstock/vitstudio

Despite its difficult geography, with 80% of its surface covered by ice, Greenland is slowly turning into a key player in international geopolitical dynamics. In this context, Donald Trump’s statements about “buying” Greenland, an offer that almost seems like a provocation, are examples of a growing interest in natural resources and Arctic trade routes.

Although Denmark has maintained sovereignty over the island, the growing attention of the United States and other powers such as China reveals how strategic this land at the edge of the world has become. Greenland is facing a geopolitical dilemma: preserving its autonomy while being drawn into a web of global economic and military interests.

New Arctic trade routes are emerging as one of the most dynamic aspects of the current geopolitical transformation. Two major passages are becoming increasingly viable: the Northern Sea Route (NSR), which runs along the northern coast of Russia, and the Northwest Passage, which connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific, passing between Greenland and Canada. With global warming, these once ice-blocked routes are becoming viable for much of the year, significantly reducing travel times and distances between continents.

The Arctic city of Ilulissat, Greenland. 123rf

Access to Arctic routes is not only a commercial opportunity but a matter of strategic security. For countries such as Russia, China and the United States, control of these routes represents a crucial economic and geopolitical advantage. China, for example, has taken decisive action to expand its influence in the Arctic region, using the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to promote the Polar Silk Road, a trade route that directly connects China with Europe and North America through the Arctic. China has also conducted scientific exploration and icebreaking expeditions, seeking to establish its presence in this strategic area.

At the same time, the United States, through NATO, is concerned about the expansion of Chinese and Russian influence in the Arctic, fearing that these powers could threaten the security of sea lanes vital to global trade. This growing interest in the Arctic has led to a militarisation of the region, with military exercises and the construction of military bases in all Arctic countries, a clear sign that the Arctic has become a new battleground between superpowers.

icebergs in Atlantic Ocean in western Greenland. 123rf

Greenland is a paradigmatic example of how global geopolitics is evolving in the context of climate change and new trade dynamics. Despite having gained increasing autonomy from Denmark since 2008, Greenland is faced with internal and external challenges. The March 2025 general election saw a surge in support for the Demokrats party, which declared itself in favour of greater independence from Copenhagen, while maintaining ties with the United States and NATO.

Although 85% of Greenland’s population does not want annexation by the United States, the island’s strategic location, rich in resources and with an increasing importance in the Arctic shipping lanes, makes it a target for the great powers. The United States, for its part, could be tempted to push for greater involvement, perhaps using as a pretext any threats to NATO’s security. On the other hand, China, despite not having a direct interest in terms of sovereignty, continues to look for ways to invest economically and acquire natural resources, as evidenced by recent initiatives in the mining sector.

In this scenario, the balance between local independence and international pressure becomes one of the greatest challenges for Greenland. While there is a desire to assert its own sovereignty, global powers are increasingly ready to intervene in this strategic area. The prospects for Greenland are therefore complex, and its choice to navigate between the desire for independence and global geopolitical needs will be fundamental in determining its future role in the new world order. (Open Photo: Arctic iceberg in Greenland. 123rf)

Riccardo Renzi/CgP

According to Shaffer, the control that the Eritrean services exercise over citizens, both internally and around the world, is so widespread that it is comparable to that exercised by the Stasi in East Germany.Because they are seen as an instrument of control and repression, the activities of gathering, analysing and sharing information and predicting threats, the secret services in Africa receive on average much less funding than the police forces. “Most African countries give priority to the police over intelligence,” says Akram Kharief, a defence and security analyst. “Although in recent years the African services have shown greater interest in new intelligence techniques and in the surveillance of telephone and Internet communications. The emergence of Islamist terrorism has encouraged more investment in the Sahel countries too.” These processes are, however, slow in decision-making compared to the speed with which new threats loom over security. “African intelligence agencies are not evolving because of a lack of transparency within them and because they are used exclusively to preserve regimes and as political police forces,” Kharief continues. “To stimulate their evolution, a political transformation of African governments would first be needed.” This, according to the analyst, is not happening in his country, Algeria: “The Algerian secret services are old, their weak point has always been excessive involvement in politics, which has now made them the skeleton in the closet of the Algerian government.”

According to Shaffer, the control that the Eritrean services exercise over citizens, both internally and around the world, is so widespread that it is comparable to that exercised by the Stasi in East Germany.Because they are seen as an instrument of control and repression, the activities of gathering, analysing and sharing information and predicting threats, the secret services in Africa receive on average much less funding than the police forces. “Most African countries give priority to the police over intelligence,” says Akram Kharief, a defence and security analyst. “Although in recent years the African services have shown greater interest in new intelligence techniques and in the surveillance of telephone and Internet communications. The emergence of Islamist terrorism has encouraged more investment in the Sahel countries too.” These processes are, however, slow in decision-making compared to the speed with which new threats loom over security. “African intelligence agencies are not evolving because of a lack of transparency within them and because they are used exclusively to preserve regimes and as political police forces,” Kharief continues. “To stimulate their evolution, a political transformation of African governments would first be needed.” This, according to the analyst, is not happening in his country, Algeria: “The Algerian secret services are old, their weak point has always been excessive involvement in politics, which has now made them the skeleton in the closet of the Algerian government.”